Akram Khan’s re-worked “Giselle” at Sadler’s Wells ended with the packed-house audience rising as one with a standing ovation. Many months ago, even before Khan had finished devising it, the production was already being advertised as the hottest dance ticket of the year. Sell-out houses and rapturous applause suggest confirmation of predictions of excellence.

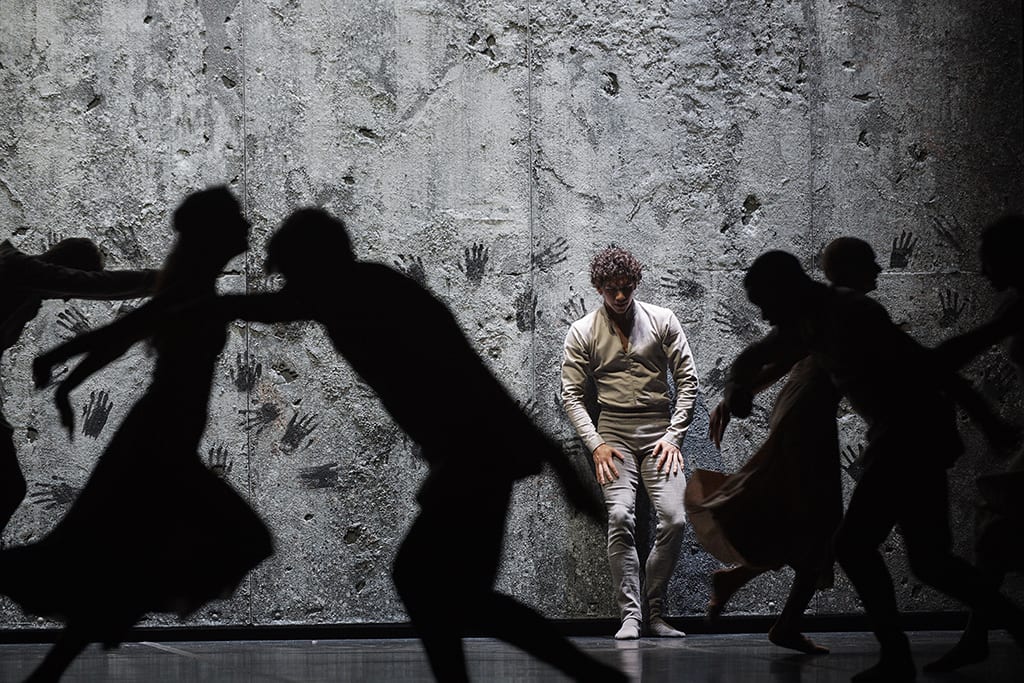

This “Giselle”, comprising gorgeous contemporary design and lighting, aside from its title and the use of the Wilis bears little relation to the original ballet with all its iconic gravitas in dance history. Khan transposes the classical setting from Ruritanian Europe to an Asian garment-factory set in front of a great wall. Sumptuously garbed industrial landlords replace feudal royalty. Giselle stands up bravely to the landlords in contrast to the exploited employees who alternately operate the landlords’ machines and become those machines. Although both the male leads pay attention to Giselle, their relations with her are left vague, unlike their well-defined classical predecessors, Hilarion and Albrecht, who mark the emotional and political parameters that the traditional ballet explores. In Khan’s Act II, the ethereal, ragged Wilis dance en pointe, armed with long bamboo sticks which make threatening patterns en masse. (The sticks don’t refer to kalaripayattu, the southern India martial art. In the programme notes Khan explains he had in mind traditional weavers’ looms.) It is not clear whether one of the men (Hilarion) wants to rape or rescue Giselle but either way the Wilis get rid of him. Giselle confronts Myrtha, saving Albrecht from a similar fate before she leaves with the Wilis.

Akram Khan has a scintillating track record. As a teenage Kathak dancer he was taken under the wing of the great Peter Brook and never looked back. He has worked with celebrities such as Kylie Minogue and Juliet Binoche, has choreographed for luminaries Tamara Rojo and Sylvie Guillem. The English National Ballet company dancers speak endearingly of him. In video interviews he is not only beautiful to look at but also thoughtful, a kind presence, and contagiously dedicated to his work.

For “Giselle” he has had behind him the juggernauts of Manchester International Festival, Sadler’s Wells, and the Arts Council England. He has had the best of designers in Tim Yip, lighting by the consummate Mark Henderson, and on top of all that, English National Ballet’s massive production and rehearsal machinery. It doesn’t get better than this. Every one of ENB’s dancers is a star and their – alternating – lead principals superb. Alina Cojocaru, almost constantly on stage, of course was breath-taking, conveying physical fragility and massive strength of character. Isaac Hernández and Oscar Chacon, as Albrecht and Hilarion respectively, also would have been magnificent had they been given the choreographic opportunity. Indeed, altogether the skills of the cast seem not much exercised and, aside from the final duet, Hernández in particular gets short shrift.

And there lies the rub. For all the hype of these traditionally trained ballet dancers being ejected from their comfort zone to perform in Khan’s dance vocabulary – there were quotations from Kathak in many of their movements – there wasn’t much to challenge them. To be sure, this “Giselle” was no imperial Petipa revival but whatever Khan asked of them, sometimes too literally, they walked it.

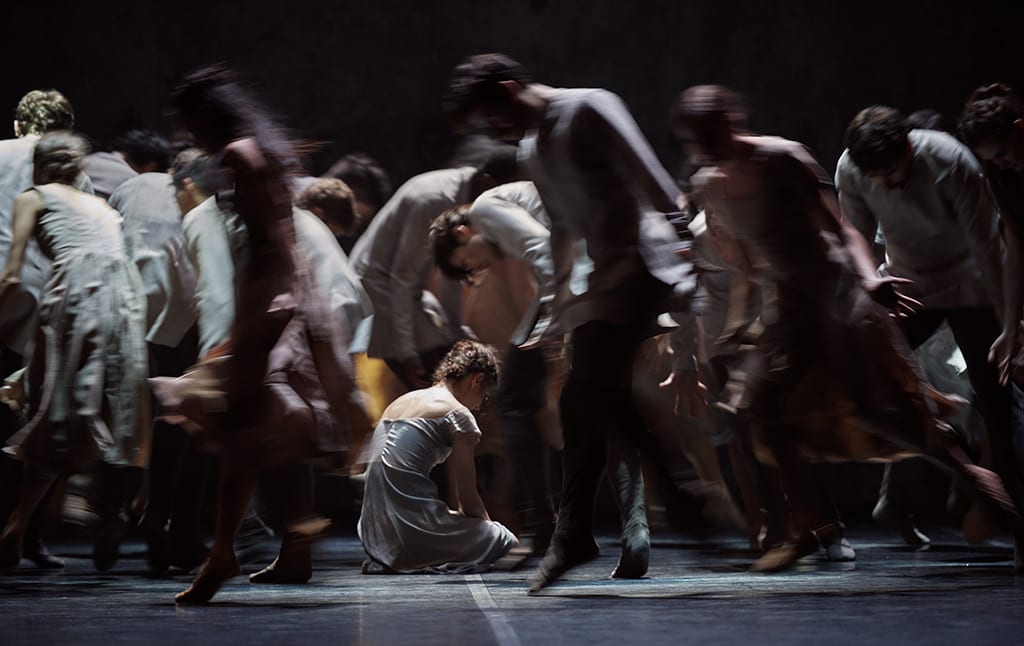

Khan’s familiar choreographic enemies remain duration on the one hand, and on the other, cast size. His works frequently forego a sense of continuity for any length of time and the more dancers he has to deal with, the more this shows. This chimes with other reviewers’ remarks about the difficulty of following the story in Khan’s “Giselle” but surely the problem is more than one of plot exposition.

Khan typically tends not to set up an incrementally connected linear trajectory for a whole piece. The impression is of an assemblage of discrete blocks of dance work, often arbitrarily sequenced and with uneven amounts of attention paid to peripheral dancers. As the emotional or narrative line is lost, so is any character development that would support that line.

In this production the unevenness in the arc of events is exaggerated by the contemporary soundscape by Vincent Lamagna. Stretches of it are intriguing, innovative, beautiful, but frequently it breaks into pieces, perhaps for technical reasons. Lamagna and his orchestrator and conductor Gavin Sutherland may have been hampered by Sadler’s Wells sound system always at whose unpredictable mercy sit punters in the front stalls, ear-plugs to the ready. As it was, while an entire orchestra sawed away in the pit, not a single instrument could be heard in the auditorium. Instead there was a homogenous blast from the monolithic loudspeakers flanking the proscenium arch. It would require an audio aficionado to judge whether the orchestral instruments were miked to an enhancement system or how much of what we heard was inserted pre-recorded. The effect was often, so to say, on-off, sometimes literally.

But nobody minded. At the end of the show, there was that standing ovation.