In a powerful and moving performance, a daughter relives her mother’s survival journey from Nazis occupied Vienna to London to final dream in the USA.

Lisa Jura, an accomplished piano player who benefitted from Professor Isseles instructions, until that is, he had to axe lessons due to new legislation that forbids the teaching of Jewish Children. It was not an easy task for a music teacher to give up his protégé pupil. As a token of profound appreciation of his 14 years old pupil, Professor Isseles gives Lisa a golden chain, which held a tiny charm in the shape of a piano.

The 14 years old Lisa faces the brutal reality of being torn from a loving family and journey with many young children on what became known The Kindertransport.

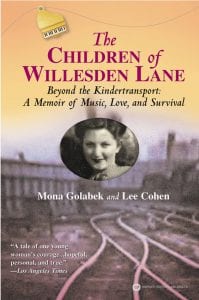

Lisa’s stamina, determination and wit inspired her daughter Mona to unfold the extraordinary harrowing story of an exceptional individual in a book “The Children of Willesden Green” which has been translated to stage by the title “The Pianist of Willesden Green” where Mona is acting the role of her mother.

We met at St James theatre where ‘The Pianist of Willesden Green” had returned for a second run due to its popularity.

Rivka Jacobson: The book and the play do not share the exact title. The play’s title The Pianist of Willesden Lane while the book’s title is The Children of Willesden Lane, which means that the narrative may be different. Can you first tell us, who is the pianist of Willesden Lane?

Mona Golabek: The pianist of Willesden Lane is my mother, Lisa Jura. And when the producer, Hershey Felder, and I crossed paths – he had read the book and heard about the story – we determined to work together to create a play, a 90-minute play, built on the story and the book. The book, of course, encompasses many of the children who arrived at a hostel, a Jewish hostel, on Willesden Lane in London; these refugee children who had come here. So we determined that the play, which had to distil so much of the book, really had to be told through my mother’s eyes, in the first person; and that’s why we chose to change the title to The Pianist of Willesden Lane, to make it very specific that this is my mother’s story.

RJ: Your mother arrives at the UK – where did she come from? Can you give us a brief synopsis?

MG: In 1938 after Kristallnacht, a clarion call went out over the BBC radio, imploring the British people to save the lives of Jewish children, and a rescue operation came into effect called the Kindertransport (‘the children’s train’). British Jews came together with Christians: they identified hostels, homes, farms to place these children, but the real rescue operation involved the trains, which the Nazis ironically allowed to take place – for six months, they allowed ten thousand children to come out. These children came from Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Germany, and a desperation set in for the families to get a ticket on those trains, which was so difficult, and then to let your child go – it was the most traumatic decision for a parent to make. In fact, some parents accompanied their children to the train station and in the last moment, would not let their child get on the train. So it was this rescue operation that brought these ten thousand, mostly Jewish, children to London.

RJ: What year was that?

MG: The Kindertransports took place from December 1938 to June 1939, before the war broke out.

RJ: Did your mother have siblings?

MG: My mother was the middle of three daughters of the Jura family in Vienna, and they had the most horrible, heart-breaking decision to make: to choose one child. They chose my mother; she was fourteen years old. They chose her because she had her music, she was a child prodigy; and they felt that the music would give her strength, something to hold onto in the darkest of times, until they could all be reunited. So left behind was Sonya, the twelve year old, and Rosie, seventeen years old.

RJ: Were they saved?

MG: The sisters, ultimately, were saved, in a very dramatic way: Rosie was always one step ahead of the Nazis, fleeing from Vienna through France and ultimately to safety in Switzerland; and Sonya’s life was saved – she came out on the very last Kindertransport operation.

RJ: Now, your mother was a pianist, she had a passion for music; was it something that ran in the family? Her parents, were they involved in music?

MG: My grandmother, Malka, played the piano, and in fact felt very close to Lisa because of the music. So that was the background there, and I think all of the Jewish families in Europe were educated, and felt closeness to classical music. This was another time, an old world; there was a reverence for classical music – remember, there was no television, there was no internet. Great culture and great music was a part of the Jewish people. So, yes, it was in their family, and they would listen to phonographs of the great artists and what not.

RJ: You perform the role of the narrator in the show, that is your mother. How easy or difficult is it to step into her shoes?

MG: The producer, Hershey Felder, who is brilliant and who adapted this story for the stage, challenged me to put a red wig on and become my mother. At first I didn’t understand where he was going, it seemed somewhat crazy to me. But then I understood that he was allowing me to inhabit my mother, and then I had to work very hard, to study, to learn how to inhabit my mother’s spirit and skin, and become her. As a young girl, I was never trained as an actress, so I went to work with a great master teacher, Howard Fine, in Los Angeles, in his acting studio. He himself was the son of survivors, so he had a deep sensitivity to the story; and he taught me about spontaneous life on the stage. He taught me about how you immerse yourself into a scene or into a character where you become that character. You live in the moment. And I’m constantly trying to understand these principles better. It’s extremely challenging; it’s one of the most brilliant art forms. The good thing was that I was a natural storyteller and I told stories throughout my life, often about music. So at least I had that training. But there was a tremendous amount of work that I had to do.

RJ: You play the piano during your performance – is that something which comes naturally?

MG: I knew how to speak and play the piano at the same time, but the challenges of this play were one hundredfold. For example, when I do a scene where I’m pretending to be sewing at a machine in the factories, because my mother would work long hours in the factories, fuelling Britain’s war effort – well, the producer came up with this brilliant idea, to have a Bach partita represent the sewing machine at the piano, while I was speaking in rapid words about the delight of a young girl being in London, the same age as the princess, and wanting to be the princess. I must have worked for months to try to be able to do that, and every night when I do it it’s still a challenge for me. So yes, it’s not easy to play and speak at the same time.

RJ: Of the years highlighted in the play, which period did your mother find most difficult?

MG: Well, my mother always talked about going down into the basement and pounding out the Grieg piano concerto when the bombs came down. She was terrified of the bombs. But I personally think that the thing that had to have been the most extraordinarily traumatic for my mother was the train pulling away from Vienna, when she said goodbye to her family. And after the war, going to the Red Cross and scouring the lists, trying to find a name from her family. I would think those would have to be the two most psychologically brutal moments for her.

RJ: At what stage of your life did your mother start unravelling the story of her past?

MG: When I was a little girl my mother taught me the piano, and in the piano lessons she always told me that each piece of music told a story; and so she told me the story of her life. So I started at a very young age to learn about my parents’ history, and about my grandparents, and this continued. When she put me to sleep at night, she would continue to tell me the story. So I was around seven, eight, nine years old, hearing this story.

RJ: And did you feel you understood her, or…?

MG: I could feel her heart, in telling me this, I could feel her soul. Of course when you’re so young, it’s so hard, but you take it in; you know the suffering, somewhere, and the pain of a parent. You feel it. And I’m sure that this is what branded my heart and set my path in life.

RJ: Your mother’s pain was really a pain of separation, to begin with, separation from her immediate family and love and affection. That must have affected her relationship with you, in a way – was she perhaps an obsessive mother?

MG: That’s a fantastic question. My mother always said that I came along to fill the hole. Renee and I came along to fill the hole in her heart. And it’s no accident that I’m named Mona and she’s Lisa – Mona Lisa, the painting, one person. She would always say I was her best friend. And I think that she desperately needed me to know what she had gone through. She desperately needed to tell the story, so that it would not be in vain. She desperately needed me to stand up, to stand for something in this world. To make those losses not in vain.

RJ: Your mother was a feisty woman; at the age of fourteen, she left a secure location and took herself to London – that’s extraordinary, really extraordinary.

MG: Thank you for noticing that. It’s one of the great moments of the play, in the story; when my mother told me how, as much as she was safe in Peacock Manor, and people were nice to her and she had enough to eat, this was not what her parents wanted for her. And she had to make something of her life, and she had to find a way to save her family. So I was always startled when she told me how she took a red bike and furiously rode it back to Brighton train station, and decided, not knowing what was going to happen, to make her way back to London.

RJ: Do you think it’s part of the upbringing, this kind of courage, determination and boldness; does it stem from the Jewish upbringing? Is it part of the long history that you have got to stand up and fight for your survival?

MG: I walk through this world as one of the proudest Jews; I think that Jewish people are extraordinary, who have blessed the world with so many gifts. And I am proud to say that I am a Jew and I am most proud of the humanity of the Jewish people: that we are the first to turn up when there is a tragedy, the first to open our hearts. We are the first to give. As long as we, as young Jewish people, retain our humanity and our humility and our sense of purpose, to be the best that we can be, from the gifts of the Torah and all the things that we’ve learned from thousands of years of survival. And if we walk with that humility, with purpose, in the world, to be who we are, but never to be apart, never to bring prejudice, never to bring a sense of superiority, or anything that can be interpreted as arrogant as we walk through the world. So it’s a fine line of acknowledging the fact that we are an incredible people, who because of the prejudice and because of the discrimination and because of the persecution, we have honed our skills and our courage and our strength to say ‘I am still here.’ I think one of the reasons that my mother’s play is so spectacularly successful now, and I say this with the greatest humility, is that it ends in triumph. It’s those last chords of the Grieg piano concerto when I pound them out, as if you’re staring into the eyes of evil, the eyes of a Nazi soldier, and saying, ‘I got through. You did not defeat me, you did not bury my people. You are gone, but we will rise up, and our children will play the Grieg piano concerto, and our children will become doctors, and our children will go forward, and still give the world beautiful things.’ That’s what I want the story of my mother to be. And I want it to be the story of man’s humanity to man, that’s what’s so important. Because of all the rhetoric now, young people out there are being radicalised into hatred, thanks to terrible language and false things about other people, in the most horrible way, radicalised to commit acts of such terrible evil – this is all wrong. And we have to find messages, which celebrate man’s humanity towards man, just like this nation opened its heart and soul to ten thousand children. We have to find a way, even as we are afraid right now, even in this major refugee crisis – the natural instinct of every human being is to want to help another human being. And yet at the same time we’re terrified: bringing a refugee in, are we bringing in someone that will cause harm to the nation? It’s a tremendous balance to find; but we have to find it. In the end, if we don’t figure out what to do, this world isn’t going to survive.

RJ: Your mother’s parents perished in Auschwitz. Did that fact and events that took place during World War II shake your mother’s faith? Did it make her resentful?

MG: As we know, so many survivors came out of the Holocaust and said: ‘What God? There is no God; how could God allow this?’ That’s the critical question, really, of the Holocaust. If there’s a God, how can God allow such terrible things to take place? I’m completely unqualified to even examine that discussion, or to know what to say, but I will tell you that my mother religiously, every Friday night, lit the Shabbat candles, and my father read the prayers, and my uncle, who was orthodox, read the prayers. And I would imagine that when my mother lit the Shabbat candles she was remembering Malka, my grandmother, lighting them. So that’s what I remember. And I know that the children in our lives, now, are doing this, and I think in the end you have to find your faith. If you lose your faith, you lose your humanity somewhere. I think so.

RJ: Now your father, in his own way, also fought in the Resistance, et cetera. We don’t hear much about him other than him being the man who fell in love with your mother and sent her a rose. Can you tell us something about him?

MG: My father, who was one of the highest decorated Jewish officers in the French Resistance, came from a small town in Poland called Łomża, near Białystok. He came from a well-to-do Jewish family, he was the youngest, and they sent him to Montpellier to study in a boarding school when he was fourteen years old – so he really grew up in France, during those formative years. And when the war broke out, he joined the Resistance and became, as I said, one of the highest decorated Jewish officers, receiving the Croix de Guerre from General Charles de Gaulle. He was the captain of an elite motorcycle brigade during the war; he was imprisoned twice in German prison camps. After the war he discovered that his family had all been killed, except for two brothers who had survived, and they reunited in Paris. They were all going to immigrate to Australia, but he had met my mother at that performance, and he couldn’t get her out of his mind. He changed the course of his life to follow my mother to America, and then married my mother.

MG: My father, who was one of the highest decorated Jewish officers in the French Resistance, came from a small town in Poland called Łomża, near Białystok. He came from a well-to-do Jewish family, he was the youngest, and they sent him to Montpellier to study in a boarding school when he was fourteen years old – so he really grew up in France, during those formative years. And when the war broke out, he joined the Resistance and became, as I said, one of the highest decorated Jewish officers, receiving the Croix de Guerre from General Charles de Gaulle. He was the captain of an elite motorcycle brigade during the war; he was imprisoned twice in German prison camps. After the war he discovered that his family had all been killed, except for two brothers who had survived, and they reunited in Paris. They were all going to immigrate to Australia, but he had met my mother at that performance, and he couldn’t get her out of his mind. He changed the course of his life to follow my mother to America, and then married my mother.

RJ: England was very good to your mother, but she left London and went to the USA. Was there any reason for this?

MG: Many of the children were told at the train stations, when they said goodbye to their parents, that they would be reunited in America. ‘Don’t worry, we’ll find you, we’ll all go to America one day.’ America was the land of hope; America was the woman with the torch welcoming the refugees. So I think when the children discovered after the war that many of them were gone, they went to live out their parents’ dream, and they immigrated to America. My mother also had family in Los Angeles who sponsored her to come over.

RJ: Your mother’s career as a pianist – did it take off in America?

MG: She did a few concerts. They were poor refugees; she started teaching piano lessons, and my sister and I came along – it was always said that we came along to fulfil the dream that was cut short for my mother.

RJ: With the play The Pianist of Willesden Lane are you trying to give your mum the platform she deserves?

MG: I don’t think I ever thought of it that way; I don’t think I ever thought of doing the play because I wanted to give a platform to my mother of the dream that was cut short. I know in my heart I wanted to do this because I thought if I could get it out there I could inspire young people to a powerful message of courage, humanity, what you hold onto in the darkest of times – like my mother holding onto her music. And these very powerful universal themes that we must never forget: what is our purpose on this earth? That is why I have committed my life to doing this.

RJ: What is our purpose on the earth? To make this world a better place?

MG: I truly believe that if we continue the path we are on, we are not going to survive, as a world. We have to find another way in this world. I think there is way too much power and wealth concentrated in very few; there is too much being done in the name of greed in this world. We have to find a way to share better, and provide. I mean, so much of the tragedy of what is taking place in this world is because young people are disenfranchised and don’t have opportunities, and then they become radicalised and start to go down these paths – because they are so angry, and so lacking, they will do terrible things. We need to walk with – like a Mother Theresa, or a Martin Luther King. We have to walk in this world with great, great humility and humanity, and make it better for many more people. That isn’t to say I don’t in any way applaud entrepreneurship, and brilliant thinking, and building companies, and becoming wealthy. I think it’s fabulous to have an idea and grow it; but I think it’s marvellous to look at people like Bill Gates, people who become billionaires and give back to the world. Ultimately, you can’t take anything with you. All you have when you come to the end of your life is, ‘who did you love?’ and ‘what good deeds did you do?’. That’s what I think is the message.

RJ: How difficult was it to write the book?

MG: Writing the book was one of the hardest things I ever did. In fact I almost got an ulcer from it. And also we wrote it through 9/11; when 9/11 happened, it was just shocking. It’s so difficult to write a book… I can’t even put it into words. The process, the gut-wrenching examination – especially writing the story of my mother and trying to be respectful of her, but you still have to reveal things. And also we were challenged to combine some characters, we had to change some scenes – we had to go back in our memories, we had to interview people whose memories were challenged. It’s a story from seventy years ago, you know. It was not easy, let me tell you. Hats off to all the authors out there in the world who are writing books – this will be my one and only book.

RJ: After St. James’, are you going somewhere else with the play?

MG: Yes, I’m returning to America where I will go to San Francisco and Dallas, where nearly twenty thousand young people are now reading the book, and studying this story, and then I will do a series of live performances of a shorter version of the play. After that I will bring the play back to New York, one day; I’m going to go back to Portland, Oregon. The producer is looking to bring the play all around America. Then we’re going to work up to the release of the feature film based on the book, from the BBC.

RJ: Who’s the director?

MG: We don’t have a director yet. The BBC just signed the deal with us and the screenwriters are writing the story right now. Robert Shapiro is the producer – he produced the Spielberg movie Empire of the Sun.

RJ: And what about Europe? What about going back to Poland, showing the story there?

MG: I would love this story to be brought there one day. The book will come out in German, from a German-Viennese publishing house, next fall. So we hope to go to Vienna to premiere the publication of the book and the documentary, and then I will do some performances there. We hope to do it in Berlin. We’re talking to folks in Geneva now – so we’re working to do this.

Thank you Mona.