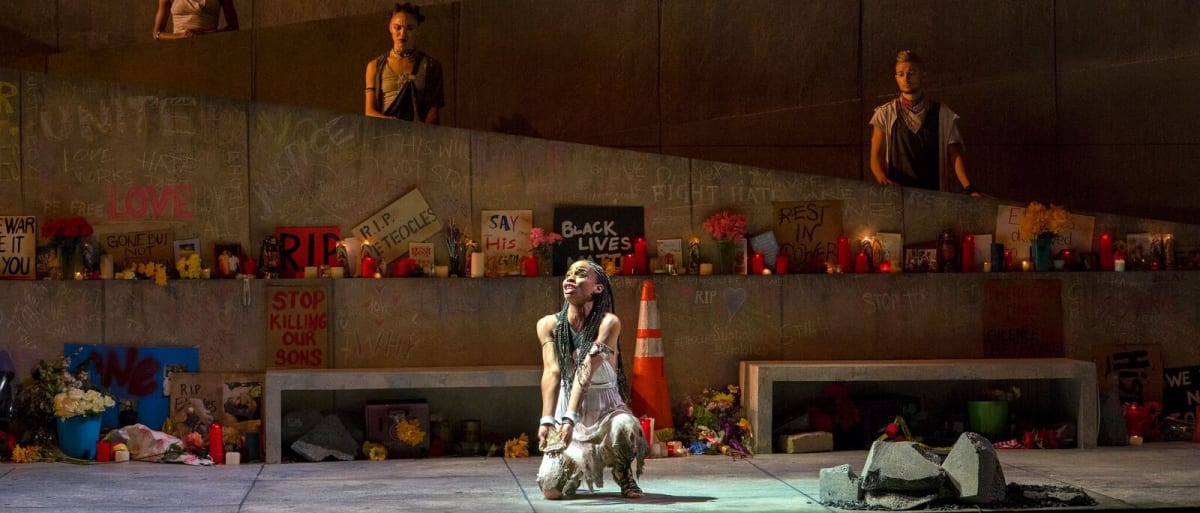

Before Antigone begins, before any lines are spoken, the set speaks volumes. Against a stark concrete wall, a memorial has gone up. There are flowers and candles and, most importantly, the hand-painted signs that read things like: “Black Lives Matter,” “Say His Name,” and “Stop Killing Our Sons.” “Unite,” “Love,” and “Justice” are scrawled in chalk on the walls. The Classical Theatre of Harlem’s Antigone enforces the chilling absence of young men caught in the crosshairs.

Sophocles’ Antigone begins after a civil war in the Greek city of Thebes, shortly after the death of King Oedipus. Oedipus’s sons, on opposite sides of the war, have killed each other in combat. With the Oedipus’s royal line nearly all dead, the new king Creon has declared that one will receive a burial of honor, and the other will have his body left outside the city walls to rot. But though Oedipus’s male heirs are gone, his two daughters still live in a city that is increasingly hostile towards the memory of their family. With her world gone, Oedipus’s daughter Antigone decides she would rather die than leave her brother unburied and dishonored.

The senseless death of young men is the catalyst for Antigone. But Antigone herself embodies feminine power. Alexandria King is a fiery Antigone whose very body is in a constant state of resistance, poised with fists always clenched, brow always furrowed, and every muscle tensed. Her athletic form seems always ready to fight, and she speaks forcefully, with a total fearlessness of death, punishment, or any of the men who tell her how weak women are.

At nearly two and a half thousand years old, this Greek tragedy feels more dangerously relevant than ever. The Classical Theatre of Harlem, a company skilled at infusing old classics with their own personality, have zeroed in on the urgency of the ancient themes. Self-styled as “Afropunk” and “dystopian,” this production of Antigone is thrillingly anti-establishment. Ty Jones as Creon strikes an imposing figure as a charismatic monarch, with a sweeping cape and his every word underlaid with beating drums. It doesn’t hurt that Jones brings with him all the clout and respect that come with his position as the Artistic Director of CTH itself. But the instant things go wrong for Creon – and much sooner than he’d anticipated – his insecurities bring his facade of power crashing down.

Though true to the original, CTH’s Antigone occasionally upgrades Sophocles’ words – one of the company’s many flairs that evokes audible reactions from the audience. A messenger brings much-needed comic relief to this dark play. He answers Creon’s regal dialogue with a modern vernacular and even throws in impressions of Mr. T and Barack Obama. And later, when Creon asks the Greek chorus: “You think I should concede?”, the prompt answer is: “Is Harlem still black?”

CTH’s Antigone is frightfully visceral. Sirens blare against a war-torn backdrop of smashed concrete. More than once, women are ripped from each other’s arms by soldiers in uniform. Police scanners and static cloud the air, and mournful humming reminds us of the people behind the political struggles – represented in part by a Greek chorus that plays many roles. They chant, they preach, they sing the gospel, and they dance bewitchingly. But most importantly, they represent the people’s desire for normalcy. The Chorus leans on authority like Creon because he promises peace. “Let’s try to forget of war,” they tell each other excitedly in front of the Black Lives Matter memorial. They learn too late that their condemnation of Antigone in the name of the law would only give them one more person to mourn.