One of the highlights of this year’s “In” edition of the Avignon Festival is avant-garde director Meng Jinghui’s adaptation of The Teahouse, a major Chinese work written by Lao She and published a few years before the Chinese Cultural Revolution. It draws the portrait of the Chinese people at three key moments of the country’s history: the Empire at the end of the 19th century, the Republic of the 1920’s, and after the end of the second world war.

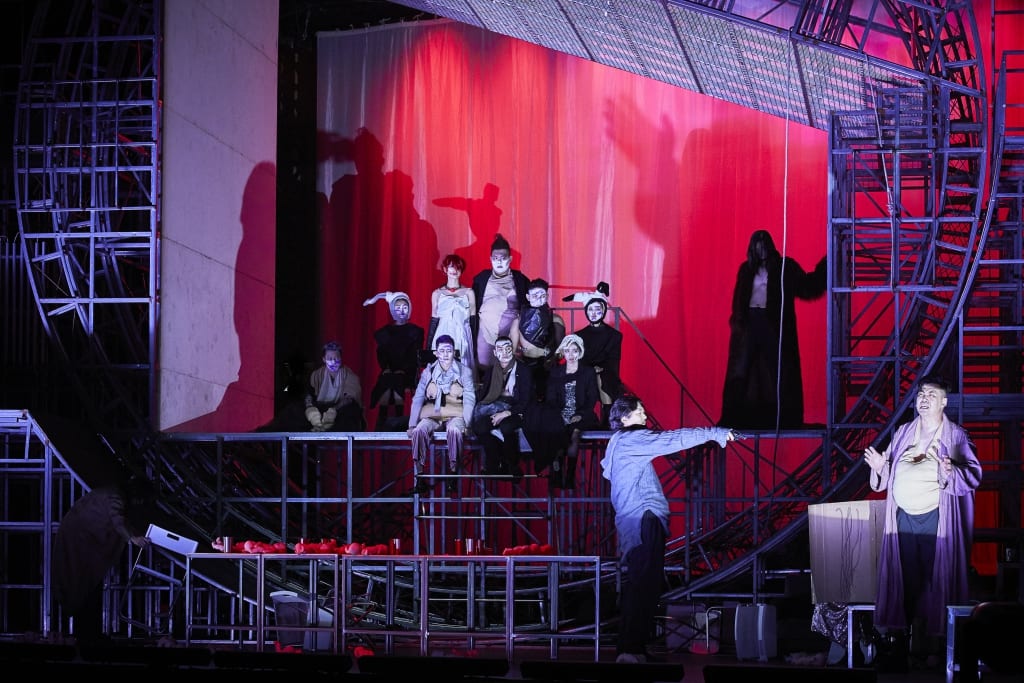

From the beginning of the play, the scenography, designed by Zhang Wu, strikes by its excessiveness. A huge metallic structure with a circular wheel in the middle is standing in the center of the stage. Some actors are in the wheel, some are on the floor: the structure symbolises the tea house that gives its name to the play. Combined with this impressive structure is Wang Qi’s work on lights. They are both colourful and violent, creating a unique aesthetic. Director Meng Jinghui describes his mise-en-scène as ‘expressionist’ and ‘full of contrasts,’ highlighting the fact that for him, the shadows of the actors are as important as the light on their faces.

There is indeed a dark side to Teahouse, in which blood is spilled more often than tea, and which has a physically painful dimension. The actors’ exhaustion can be heard in their voices, breaking from too much screaming, or can be seen when one of them tries to stay on his feet in the giant wheel that makes him look like a hamster determined to rebel against the system.

Though the characters repeat that it is important ‘not to speak of affairs of state,’ the play is very political. The text itself is, and the mise-en-scène is extremely subversive. It challenges the spectator only with its length (a good 3 hours) and by the doubt that it sometimes creates: it is theater or not? It also uses shocking language and imagery, including several faked suicides, people eating babies, buckets of fake blood being spilled on everyone (reminding of Ivo Van Hove’s Les Damnés), and a man sawing a mannequin in two parts.

The spectators themselves are questioned and mocked by the main actor’s improvisation. Why are we here? Do we think going to cultural events will make us better people? Some of his speech is not translated but I can understand that its irony is efficient, according to my Chinese neighbours’ laughter.

The public’s reaction to the play proves that it is still extremely relevant today. Lao She’s text is adapted to our contemporary, eclectic culture, which mixes pop-rock music and a rap summary of the play. Meng Jinghui dresses a bitter caricature of our world, ironically paying homage to Coca-Cola and parodying a McDonald’s drive-in when a customer says: “I want a piece of freedom.”

Teahouse is an ode to rebellion and subversion, even during the final applause. The classic final salute transforms into what seems to be the beginning of a rave party. The actors and the director dance frantically to loud bass music, and when the wood panels close, they open a door through it to keep on thanking the public.

Summary in French:

Avec son adaptation du classique du théâtre chinois La Maison de Thé, le metteur en scène Meng Jinghui réalise une pièce d’avant-garde comme on en voit peu. Mettant à l’épreuve à la fois les spectateurs et les acteurs sans jamais perdre en intensité ni en sens, le texte de Lao She trouve dans cette mise en scène un écho contemporain qui rend hommage à son caractère subversif.