The spectacular dramatic opening scene of the first of The Oresteia trilogy sets a splendid prelude to Adele Thomas’s production of Rory Mullarkey adaptation of Aeschylus’s epic.

This three-hour version includes two intervals helps to define each of the three plays within the trilogy, punctuating the differences in mood, lyric, tone and action in each story. The issue of retributive justice, where one sin is punished by another, runs through the trilogy.

The dramatic opening, where mist lifts from one side of the audience standing area, diverts attention from the backdrop of wooden boards, with some graffiti, evocative of recent turmoil in Greece of today, to the watchmen, at the opening of Agamemnon. Dressed in a modern black jump suit, the watchman gives a vivid account of the weariness of the past ten years of his waiting for the beacon light to appear, to indicate the end of the Trojan War and the triumphant return of the Agamemnon. And then, the window in the gable above the stage, opens and a torch is lit. Like a match thrown into a bonfire the tragic story unfolds. In the watchman’s words:

“If this house could talk

It would heave horrors out of its mouth. “.

And the bowels of the palace have gradually been exposed letting a stench of blood to linger and horrors of revenge to dominate the first two plays.

George Irving’s Agamemnon is of an uninspiring king. There is nothing heroic in his return apart from chariot and his garb. He is dressed in a Roman outfit, unlike Clytemnestra who wears a long dress with geometric pattern on it. Is it to mirror their doomed actions? His sacrifice of his daughter to appease the gods, which is an act of that time, versus Clytemnestra, timeless pain and desire for revenge as a mother and a wife.

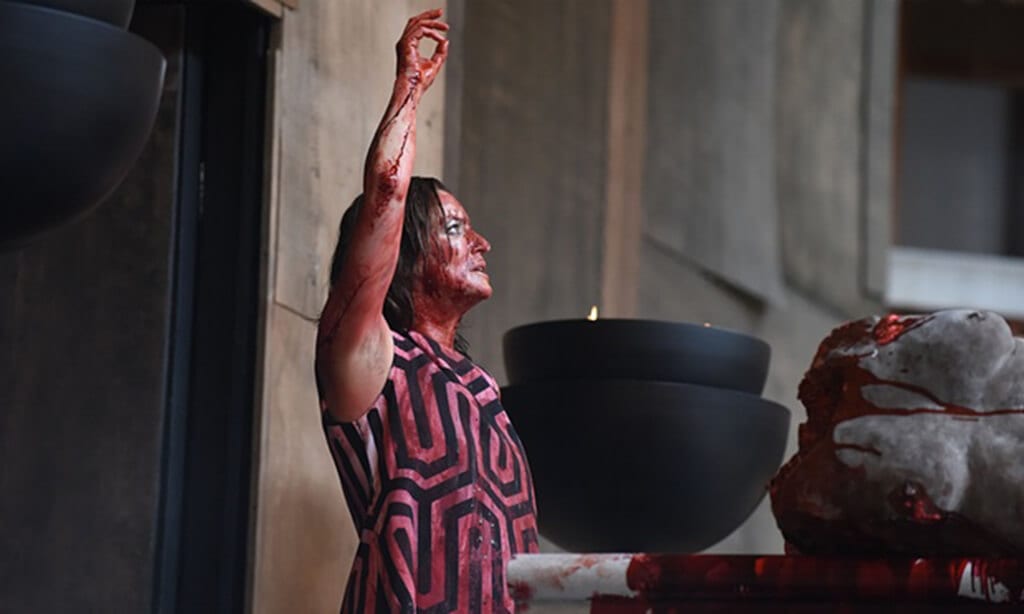

Katy Stephens’s Clytemnestra is outstanding. She commands the authority of a Queen in charge of a palace. She nobly, yet with a tinge of sarcasm, manages her outrage as mother, who had ten years to plot her revenge for the slaughter of her daughter. She does not flinch as an insulted wife, when her husband brings home with him, his new conquest, Cassandra. She executes her plan with military precision. When she appears covered in blood with a sword in hand moving triumphantly behind an alter-like platform, drenched in blood, from the mutilated bodies of her husband and his Trojan princess, Cassandra, she powerfully delivers her case for carrying out this bloody deed.

Acting Cassandra, Naana Aggyei-Ampadu’s silence in the chariot, is as eloquent as her song and movement. She conveys with passion, and impressive singing voice, the character’s pains and knowledge of the sordid end awaiting her.

Joel MacCormack’s challenging Orestes, appears in Choephri, the second trilogy. Movingly, yet not sentimentally, he conveys the depth of the psychological and moral torment in his duty to avenge his father’s murder. The dramatic effect is conclusive – Oresteia’s matricide, not driven by evil thoughts, but by the order of the gods, makes that action credible. Members of the chorus, six males cladded in modernish suits, hats with two brollies, and two females in pencil skirts individually and collectively weave in and out and the storyline as participators and observers.

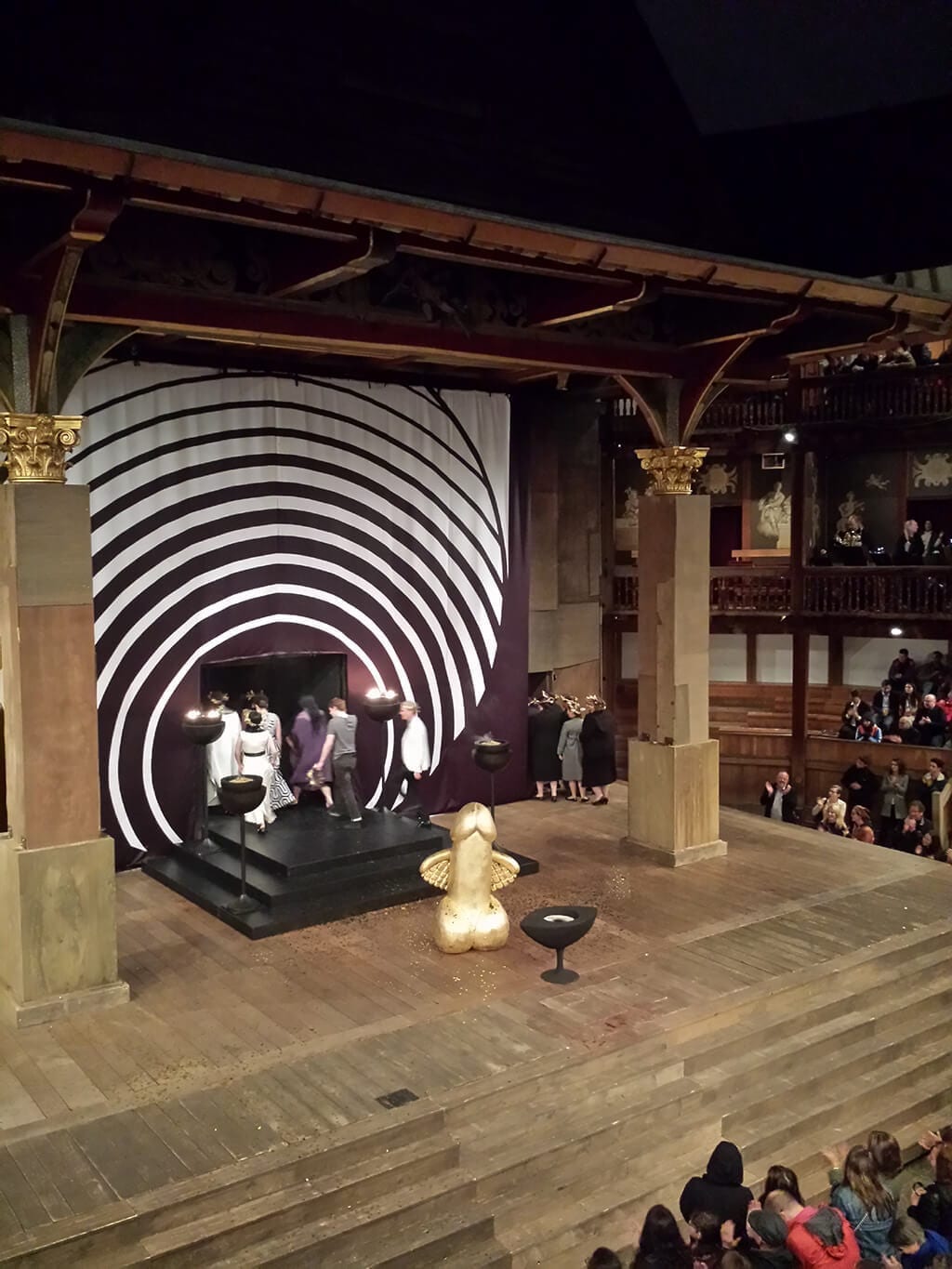

In the last of the trilogy, Eumenides, one is left bamboozled. The dramatic chorus of the Furies dominates the scene, their Danse macabre is rather odd, to say the least, yet the ending is upbeat, with the gods replace by a large golden winged-penis. After so much blood and gore, the audience deserve some relief, with humour and a cheeky touch.

The plays are full of dramatic symbolism, horror and humour, which Adele Thomas, Hannah Clark, designer, and Mira Calix, the composer, exquisitely interpret and convey in this moving, yet exciting production, which rightly pins it to no specific era.