It’s certainly au courant and hip to revere the work of Bertolt Brecht, and undoubtedly he’s worthy of this acclaim. Overall, his body of work is not only insightful, compelling, and thought-provoking, but it also seems ever relevant to emerging and changing social and political issues. Still, each of his plays and every performance should rise or fall on its own quintessence. For example, while several of these laudable characteristics were present in the performance of The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui at The Wild Project, many remained obscured. This is certainly not one of Brecht’s better plays, nor was it one of the better performances imaginable. The play is unreasonably long and unnecessarily repetitive. Perhaps Brecht recognized its potential for tediousness and suggested it should be performed with considerable celerity. Regrettably, last night his recommendation went unheeded. The play moved at a snail’s pace, and, especially after intermission, the snail made its way to the end well before the play. This was unfortunate, particularly because the audience came close to sleeping through or leaving before the powerful closing line: “Do not rejoice in his defeat you men,” warned Arturo Ui, “for though the world has stood up and stopped the bastard, the bitch that bore him is in heat again.” Here, Brecht alludes to the ultimate fall of Adolf Hitler but warns us that another tyrant will one day appear on the global stage, a point of considerable saliency as we witness the meteoric ascension of Donald Trump.

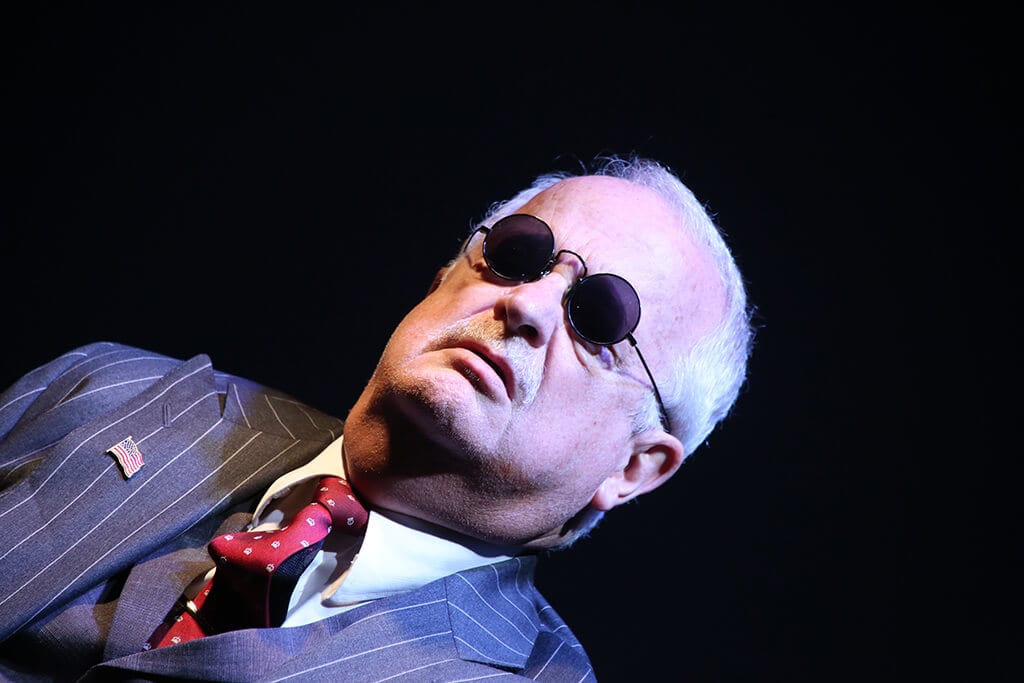

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui is a parable that examines the foundations of autocratic power. Brecht tells the story of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Nazi Germany through the criminal ascent of the play’s protagonist, Arturo Ui, a Depression era gangster in Chicago. Like Hitler, Arturo Ui did not originally seem destined for domination. He was weak, incapable, ineffective, and awkward. Through sheer force of will and with the capable assistance of a cast of ruthless and merciless henchmen, both these men threatened, terrified, extorted, and eliminated all those that impeded their rise to absolute power. And as Hitler subjugated Austria and Poland, Arturo moved his criminal empire into Cicero and Minneapolis, wreaking fear, terror, and death wherever they went.

The connections by which this allegory is developed are complicated and even tenuous at times, but the storyline generally works. To reinforce the lucidity of the parable, the speeches of Hitler are superimposed on a screen while Arturo Ui bellows about his desire to take control of the grocers and shipyards of Chicago. Additionally, when Arturo hires an inebriated actor to teach him the body language of the stage, the actors wind up goose-stepping and giving the Nazi salute. This is all helpful in driving home the play’s central theme, particularly because neither the director nor cast seem able to determine whether the play should be performed as farce, slapstick, historical fiction, drama, or comedy. As a result the performance seemed to move arbitrarily from one art form to another. In fact, during the important trial scene, when an unknowing dupe was convicted of arson, the actors all seemed to interpret their roles and functions differently. The judge especially seemed out of sync with most everyone else, and the scene became incongruous and ridiculous. Consequently, the parable was obscured, at times, throughout the play.

Despite all, there were moments of radiance and distinction throughout the show. Antonio Edwards Suarez, playing Givola, one of Arturo’s henchmen, and Elise Stone, as Mrs Dulfleet, put in exemplary performances. And even one of Brecht’s less notable plays is usually still worth a look.