Suit the action to the word, the word to the action, Hamlet famously exhorts the players. The vigorous fusion of word and action in Bedlam’s madcap production of Sense & Sensibility does just that.

At its heart is the brilliant distillation of Jane Austen’s novel of over 119,000 words to stage action by Kate Hamill, as well as the dynamic inventiveness of its director, Eric Tucker, and the ten-actor cast. It is a theatrical reappraisal of Austen’s story of two sisters who embody reason (sense) and feeling (sensibility) and the struggle to comply with their society’s demands for its highest accomplishment: a suitable marriage. The satirical side of this solemn notion is grist for theatrical hijinks.

The audience is greeted with John McDermott’s captivating set, an all–white assemblage of trellises, chairs, tables – all on wheels. The walls at either end of the raw space are covered with huge oil paintings of the novel’s landscape. Among the many jewels of the set is a tiny framed etching in the far corner of Miss Austen herself.

The actors as actors are not hidden from the audience. We see them in their dressing room before the show, then roaming the stage in rehearsal skirts and denim and hoodie jackets, as we hear the Supremes’ “You Can’t Hurry Love.” When they shed their contemporary clothes to reveal a simplified but elegant Regency mode, the movements and music morph. We are transported back to Jane Austen’s world.

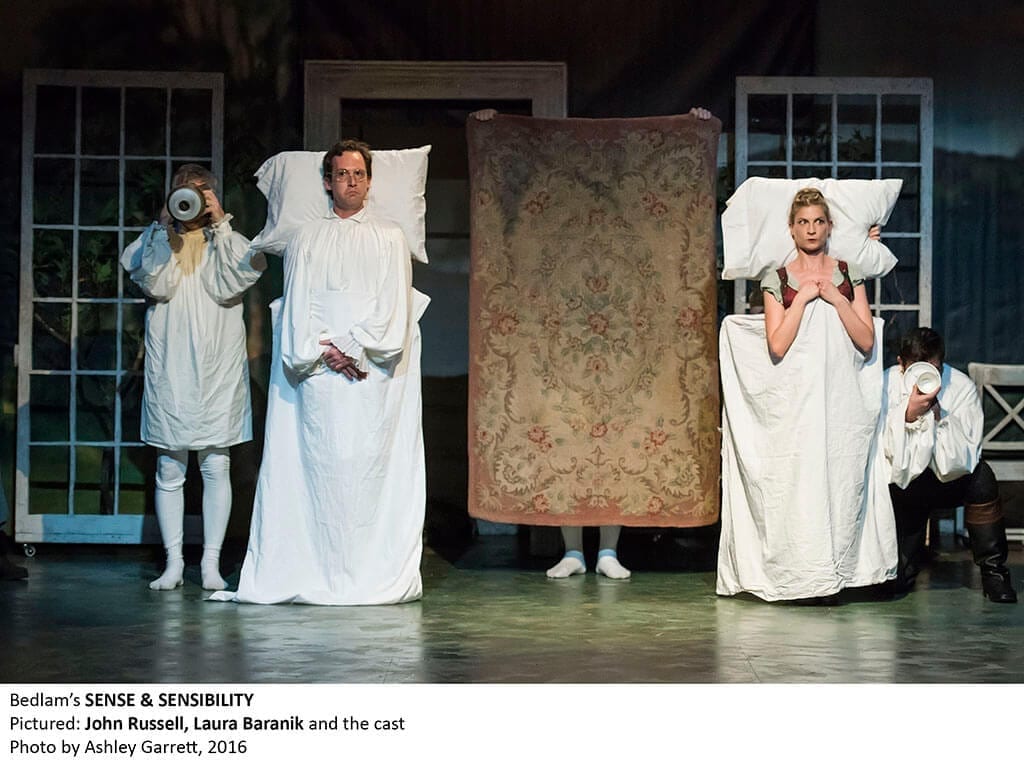

The production’s inventive, humorous style is established when the elder Mr. Dashwood appears on his deathbed. The actor stands, the ensemble holds up a sheet and a pillow, and the actor stands behind the sheet, resting his head on the pillow. Across the stage, the next scene begins in another bedroom where Mr. John Dashwood (John Russell) and his avaricious wife (played with delicious nastiness by Laura Baranik), chat and ultimately twist the law for their own economic benefit, disregarding the welfare of their relatives.

After this we are swirled through Austen’s scenes as the tables, chairs, a lovely settee and those trellises swivel and rotate the characters and their fates. All the actors, with the exception of the two sisters, assume other roles with only minor changes to their basic Regency costume.

What is remarkable in this swirling production is that the adaptation by Kate Hamill (who also plays a vibrant Marianne) is loyal to Austen’s dialogue, sculpting it out of the narrative while at the same time leaving space for the subtext to flourish through action, as during the first encounter between Elinor (Andrus Nichols wonderfully maintains a delicate restraint as she reigns in her inner tumult) and Edward Ferrars (Jason O’Connell), when the table revolves with the help of two other actors, thus enhancing the emotional upheaval within Elinor and Edward.

This is the theatrical genius of the Bedlam production: actors are characters, delightful caricatures, set pieces, barking hounds. There is that magnificent moment when Willoughby takes Marianne for a wild and thrilling ride in his carriage. The carriage and its horses are created by the bodies and sounds of all the other actors.

The broad comic strokes are given to the minor characters: Sir John Middleton (Stephan Wolfert), hilarious with his toothy, overly cheerful yet sincere smile, and Mrs. Jennings (Gabra Zackman), the well-meaning gossip whom we nevertheless adore, along with Robert Ferrars (Jason O’Connell), Edward’s fanatically fixated, dipsomaniac brother. Their words are the satiric salt for the wounds of the more humane, complex characters.

This production is, I am happy to impart if I were the novelist, highly agreeable to all senses.