There is no shortage of art that comments on the current administration. Revivals and new plays alike are prone to this scrutiny by a modern American audience. Colin Teevan’s stage adaptation of Ryszard Kapuscinski’s The Emperor is no exception, but it portrays neither the ruler nor the oppressed, but those who perhaps knew the ruler more intimately than anyone else: the servants, steadfast in their duties, and unsparing of their secrets. After the fall of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, Kapuscinski interviewed the few surviving members of his court, who are all played with distinct and unforgettable dexterity by Kathryn Hunter.

The play’s minimalist concept (especially the unrestrained quality of Mike Gunning’s superb lighting design) gives the drama over completely to Hunter and the impeccable musicianship of Temesgen Zeleke. Director Walter Meierjohann is wise to impose as few scenic and multimedia elements as possible to give Hunter full reign of the play’s storytelling. However, through all the play’s earnestness and simplicity, the urgency of war, famine, and autocracy take a backseat. The material itself plays out like a documentary: the details peak some interest but it does not by its nature inspire a “what happens next” excitement. There is no great dramatic figure like Hamlet, or a Macbeth, or a Lear onstage here, but only Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the fool, the porter, and the gravedigger. As a result, the evening seems to fall between a damn good clown show and an epic. The adaptor even admits in his program note why the material doesn’t entirely lend itself to drama.

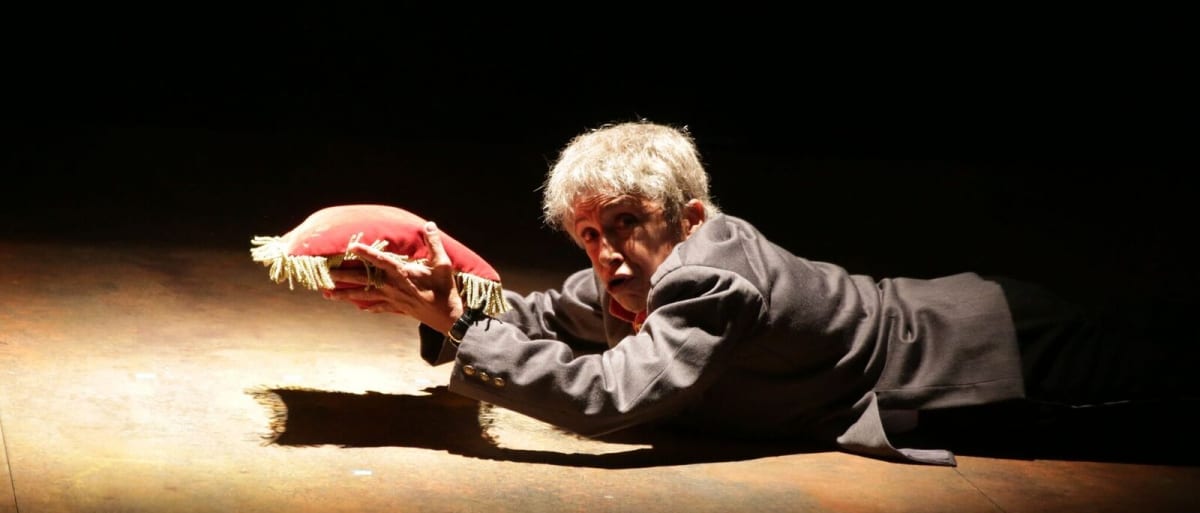

Hunter’s showcase of a performance is something very special to behold. Her genuine nature shines through all of the eleven characters she plays, making her all the more compelling, as she makes no effort to transform, but only to bring forward another side of her humanity. It is through her alone that the play’s most moving moments land with weight. A legend of the theater in this intimate of a production, working only with the bare essentials: a treat, a privilege, and the reason you may want to snag a ticket.

As a result of all the servants’ palpable admiration of their great ruler, the story of one autocrat’s downfall is told with explicit detail, but not condemnation or vengefulness. This may make some curious, and leave others hungry for catharsis. A liberal audience certainly will be want a political play that reads like a call to action, but this is not such a play. Audiences are asked to view these men not as complicit or foolish, but as doing the best they can.

We know, unfortunately, that not much will change as a result of these men being given voice – the rulers will still continue to rule, the servers will continue to serve. But perhaps it is less about the valiant attempt, and more about the possibility of listening deeper, which is a herculean effort in itself.