You have to love her, Alfredo!

Alphonsine Plessis (aka Marie Duplessis) has to have been one of the most charismatic women of her era and this is the biography that shows it. After a childhood of abuse and poverty, she arrived in Paris, did some time as a seamstress (a bit like Mimi of La Bohème fame?), and ended up perhaps the most famous courtesan of the 1840s. She could have been a character in a novel by Balzac or Zola and her story certainly traversed a lot of the material and themes that fascinated them both. Her tale was, of course, transformed into a novel by one of her lovers and admirers, Alexandre Dumas fils, who told her story in his quasi-autobiographical novel La Dame Aux Camelias (where he renamed her Marguerite Gautier and is taken by most people to be the model for the character of Armand Duvall) and in a play he adapted from it. That play inspired Verdi, in his turn, to create the opera La Traviata (where he renamed his heroine Violetta Valery and her young man Alfredo Germont) which was not only inspired by his reaction to the play but by the situation he was living with his own then-lover, later-wife, Giuseppina Strepponi, who had been a stellar opera singer, a kind of Maria Callas figure, in Italy years before and involved in helping Verdi in the early days of his career. Perhaps the “real” Traviata should be considered to be, as Gaia Servadio insists in her excellent book of the same title, Giuseppina Verdi. But now it is Alphonsine herself who is the subject of this biography about a real “traviata”.

The legend of this woman has continued to inspire and fascinate – Bernhardt and Duse famously playing the “traviata” in the play (George Bernard Shaw wrote about how differently each approached the role)and, Callas and others playing her in the opera. Get the recordings, get the DVDs – it is almost impossible not to be caught up in the tale and moved. And do not forget to seek out the astonishing Greta Garbo’s interpretation of Marguerite in the brilliant George Cukor film Camille, based as much on the play as on the novel. She certainly knew by instinct how to play this character; and this is the character, pretty much, that you find in this excellent biography. If you are fascinated by the various versions of this story then this book is informative, accurate and ultimately a compelling must-read.

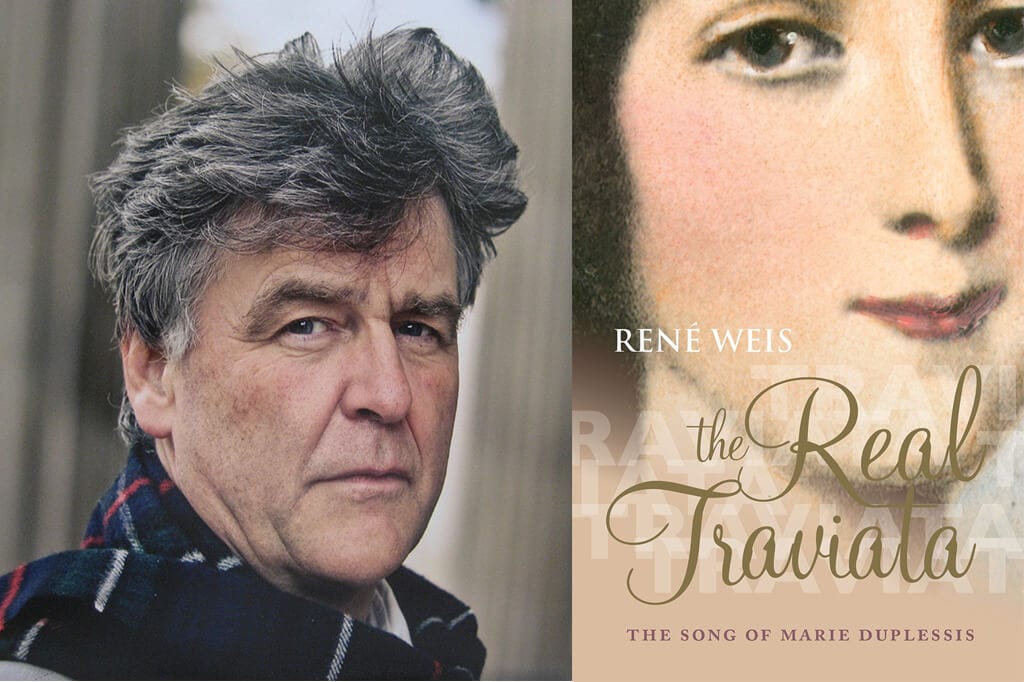

Professor Weis’s book that tells the story of this fascinating, surprising woman has been well-researched and well-enough written and it is utterly appropriate that it should be published by the Oxford University Press, because the scholarship is extraordinarily thorough and the conclusions presented based upon it completely convincing. This is important, because the tale is, like the novel and play and opera that it inspired, immensely dramatic and thought provoking and the character of the doomed courtesan poignant and tragic. Alphonsine is also, perhaps, a kind of precursor of Coco Chanel or Edith Piaf, who similarly roses from the kinds of background that in earlier eras before the Enlightenment and French Revolution would have almost definitely precluded their successes. Perhaps that is one of the reasons that the story of la dame aux camélias is so potent. All the drama of her fateful story is conveyed in this book, so that one begins to understand a bit of what the people who fell for Marie Duplessis must have experienced, and it is all the more convincing and moving because you can believe in the well-researched details that Weis sets before you. The book is also very strong on the context of the era, the social background, and an underlying sense of the strictures society, expectations and unquestioned patriarchal attitudes placed on the lives of women.

Professor Weis is up-to-date with all his research and his awareness of the work of others. For instance, until recently it has not been known how Alphonsine went from being a very attractive but under-educated kept women of fifteen to being a dazzling star of the highest levels of society. The answer is a Pygmalion figure that turned this country-girl Eliza Doolittle into the figure who still inspires us.

Her new lover set about transforming the girl from Normandy into the queen of Parisian courtesans. He exposed her to a barrage of teachers, each the best in his discipline in all of Paris. If she could just about read and write at the start of this relationship, by the time it had run its course eighteen months later she owned a library, played the piano, and had shed all trace of a regional accent. She now appreciated opera and her instinctive refinement and good taste in clothes were given their full head. By the time she died her library included volumes by Byron, Châteaubriand, Hugo, Lafontaine, Lamartine, Marivaux, Molière, Rabeleais, Rousseau and Scott. One of her friends later commented admiringly on her ‘prodigious memory’. …Her favourite novel was a scandalous eighteenth-century romance which also became the subject of a great nineteenth-century opera, Manon Lescaut, a work that celebrates the madness of illicit love and sexual licence.

You can see why Garbo was a good choice to impersonate and inhabit such a woman on screen where, as in the novel by Alexandre Dumas fils, the book Manon Lescaut is a pivotal prop binding Marguerite and Armand and also a superbly chosen symbol. And the Pygmalion in her life who set her on the road to these heights? It was the Duc Charles de Morny, half brother of Napoleon III.

Weis’ professorial approach, dry style of writing and admirable scholarly backup do, however, rather frequently make for a bit of plodding. The story line tends to get stalled in the detail. I began to put little brackets in pencil around information that I felt could have been better handled in footnotes to improve the general flow of the narrative; but the story and all the characters are so fascinating that ultimately this is merely a quibble. I did find myself having to dilute the experience by reading a biography of Frank Sinatra between bouts with Marie Duplessis, but I also felt compelled to go back and read the next chapter of The Real Traviata after each session with Sinatra until I had read the whole book.

So my advice is: stick with it if you feel a bit overwhelmed in the early chapters by the detail. The story of Marie Dulessis, of her abusive father and tragic mother; of how she made herself into a legendary grande horizatale in the highest levels of society and the arts; of her many fascinating relationships, of her loyalties, all this is in itself, worthy of another novel; and it is impossible not to muse about how a comparable young woman would succeed in today’s world and what spheres she might conquer. Also, of course, one cannot help wondering what would have happened to Marie herself in an era in which tuberculosis need not have killed her at the age of 23. Had she lived, who knows what heights she would have risen to, whether she would have married a rich and powerful man (or stayed married openly to the one she did marry), whether she would have developed into the next George Sand or a great actress? Her life embodies – and possibly inspired – tales such as those of Nana or Amber St Clair in Forever, Amber. She is a woman from an outrageously limited background who sees her chances and seizes them and transforms her life and her destiny. In our era she would probably be an international celebrity, ubiquitous on Google and You Tube.

The meticulous research that Weis has undertaken also takes us into the world of artists such as Dumas fils and Franz Liszt, into the politics and arts of the era – Marie Duplessis ran an important salon during her brief period as a minor celebrity of her world – and into the world that was being so perfectly recorded and reported by Balzac or in the tales about the Bohemian life of that very era by Louis-Henri Murger. Weis deals persuasively with both the glamour and the seediness of the Parisian worlds in which his heroine lived and developed. Alphonsine/Marie moves from the lowest levels of provincial society to living among the highest levels of Parisian power. She comes across as a major figure in that era, always feminine, always appealing, often defiant. She was clearly not only beautiful in a way that made men wish to cosset and protect her, a petite creature of physical allure and delicacy, but she was also acknowledged to be witty, supremely intelligent, a quick learner and a woman of reliable discretion, a woman who was clearly able to capitalise on all her personal assets. Interestingly too, most of her lovers remained loyal and protective once their affair had run its course. In other words, she was in many ways a precursor of the modern, independent woman.

Her illness and the ending she endures are appalling. She was briefly married or “united” to Count Édouard de Perrégaux with whom she had a complex relationship. Reading this book you realize that he was, in fact, the real Armand, more so than Dumas fils certainly. Perrégaux was distraught at Marie’s funeral at the Madeleine having withdrawn from her much as Armand did. Many other people were also stunned with grief.

Liszt was touring Russia when he heard the news that his lover had died. Grieving, and guiltily remembering his unfulfilled promise to take her with him to Constantinople he wrote to his mistress Marie d’Agoult: ‘Now she is dead, I do not know what mysterious antique elegy echoes in my heart at her memory.’ … He had loved her passionately and she had touched his artistic soul. … Marie Duplessis never heard this testimonial to her sweet and innocent nature. If she had known that she had meant that much to the genius of Liszt, it might have comforted her even in those dreadful final days in the Madeleine. As it was Liszt would keep faith with her beyond this immediate response in a daring and pointed musical offering, if not two.

Marie Duplessis, on top of everything else, was clearly a muse and an inspiration and we are the beneficiaries of that short, tragic and spectacularly lived life. And of course, it is the artistic offerings of Dumas fils and of Verdi that, above all, make us want to learn about the inspiration behind their works. Quibbles aside, René Weis has done an excellent job in telling us that story, backing it up with convincing scholarship and placing it in its context while also, finishing off the book after Marie’s premature death, detailing the aftermath and legacy of the life of Marie Duplessis.