The War of the Roses trilogy, a reboot of the highly acclaimed 1963 RSC adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Henry VI parts 1-3 and Richard III by John Barton and Peter Hall, now is directed by Trevor Nunn for Rose Theatre in Kingston as a tribute to them fifty two years later. The original adaptation was celebrated for its ground-breaking, even rebellious approach to adapting Shakespeare’s history plays, its acute topical relevance and its impact on revitalisation and commercial success of less known classic repertoire. Nunn’s staging of it is at best a theatrical nostalgia trip. At worst it is a tedious, escapist and irrelevant historical romp.

No doubt there is a generational gap that needs to be taken into account. We are now used to ethnic diversity on stage, more variation in accents and different acting styles. Most of all, the world around us has changed and antiquated theatre paying attention to imagined historical verisimilitude can only result in the presentation of entrenched stereotypes and pageantry. Today it is truly horrifying to watch one of the ugliest chapters in English history, used as Tudor propaganda to show how England and its people were destroyed by greed and power games and Nunn’s anachronistic approach to staging the Wars of the Roses may convince UKIP to make Shakespeare’s history plays a compulsory reading. In many ways the trilogy directed by Nun as a spectacle of pageantry and English pride can be perhaps read as a satire on England and its relationship with Europe, and a satire on nationalism and bickering politicians in general. Perhaps.

The French Whores

If you are not ready to consider Nunn’s Henry VI, the first segment of the trilogy, a pastiche, which is not this production’s intention, you might find it not only superficial and childish but also ever so slightly offensive. After the death of Henry V, English aristocracy of the houses of York and Lancaster begin their fight for power and control over the country and its child king. As time goes by the situation worsens, the grown up Henry VI is a weak monarch dominated by his powerful uncles while the war with the French rages on. The first alliances and conflicts are formed over the dead king’s coffin and Duke of Bedford leaves immediately for France to quash the war led by a young woman, Joan of Arc. Although the dramaturgy of the adaptation is flawless, old-fashioned RSC-style, accentuated, sonorous acting, lack of interesting stage movement (I do not count endless sword fights which all look the same) and reliance on stereotypical modes of behaviour make most of the characters look pompous (the English nobles) or ridiculous (the French court). However, the portrayal of Joan of Arc as a ‘French whore’ makes for a hard viewing, despite a strong performance by Imogen Daines.

For example, when Joan is captured by the English forces, instead of a tragic, nuanced scene we can see the reinforcement of an imagined historical stereotype alone. It is true this is one of Shakespearean caricatures but directors do not need to focus only on their re-enactment. The scene with Joan should have been more violent visually, she suffered horribly at the hands of the English, and it is staged almost as a polite conversation. On the other hand, the famous English general Talbot is portrayed as a martyr and becomes a saint-like figure as he delivers his final speech in the pool of light, as if the Heavens opened to claim his spotless soul. Uneven acting is a central problem of the production. Nunn’s actors tend to shout themselves hoarse and rarely show a range of emotions.

There are only few exceptions to the rule: an interestingly subdued, though at times too farcical, performance by Alex Waldmann as Henry VI and Alexandra Gibreath as Duchess of Gloucester who gives a subtle portrayal of a manipulative, superstitious wife of the Lord Protector.

At the end of the day Nunn’s Henry VI is a swashbuckling adventure featuring valiant if power-thirsty English nobles. It is not Pythonesque enough to be a pastiche and lacks a nuanced characterisation to elevate it to engaging, poignant drama. Perhaps we should laugh at the caricatured characters we see on stage and come away from the performance saying to ourselves we can do better than that as Henry VI proclaims at the end of the production.

The Paper Crown

Edward IV is a better-paced, more engaging and energy-fuelled segment of the trilogy. It helps that several actors who play various characters in the course of three productions come finally into their own. Michael Xavier is a good example as a shrewd, charming, scheming George of Clarence, Edward IV’s troublesome brother. On the other hand, Joely Richardson who has a chance to show her Margaret, Henry VI’ s wife, as a powerful warrior Queen defending hers, her husband’s and her son’s right to the English throne provides only a caricature, ‘a she-wolf’ of historical propaganda.

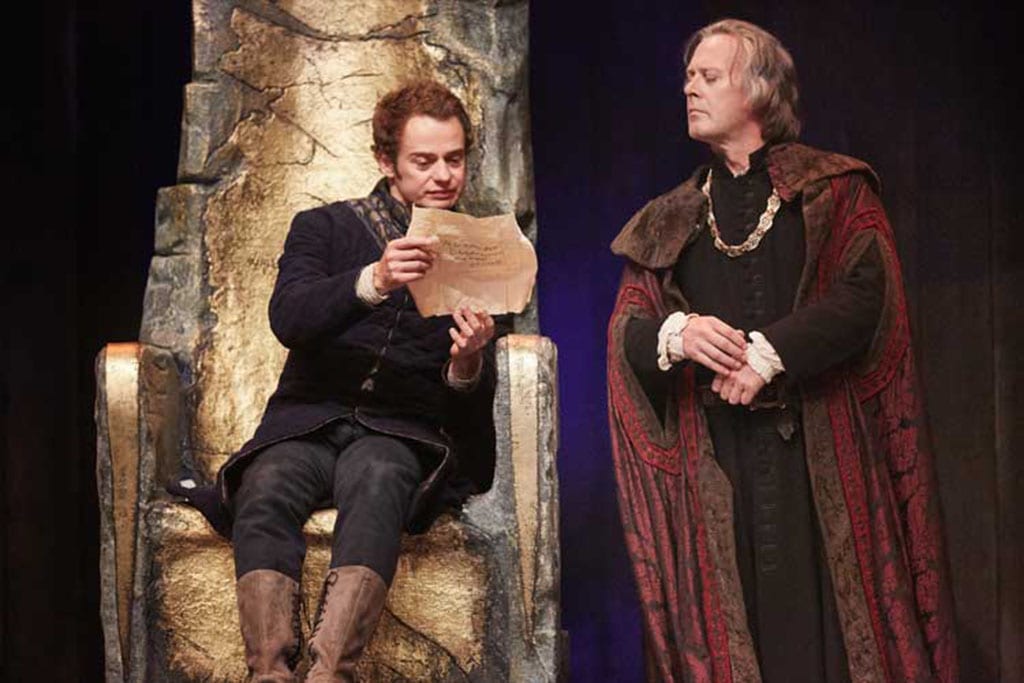

There are some interesting uses of the stage set throughout the production, especially in the ‘filmic’ moments of the staging. For example, the three very young sons of Henry VI’s rival, Duke of York, play with a paper crown on the top balcony, and as they start tumbling down the long staircase they are replaced by older actors to show the passing time; once they are at the bottom of the stairs we see three grown up men, still feuding over a paper crown, an ominous sign of the forthcoming fraternal conflict and fratricide. In this scene we meet one of the most anticipated and notorious characters of the history plays, future Richard III. Robert Sheehan is a surprising but good choice for this part. Despite his many physical deformities and spindly stature he exudes energy and charm, yet when wielding a sword he is a ruthless warrior who kills as fast as he jokes. Sheehan speaks in a slightly high-pitched voice, which makes him an odd one out in the sea of sonorous RSC twang.

The never-ending spiral of violence in Edward IV is truly shocking even if the audience are exposed only to symbolic violence on the stage: it is due to the number of deaths and the overwhelming futility of actions taken by the feuding families. The production ends with a dance in which the new royal family, led by victorious Edward IV, and all courtiers participate apart from the future Richard III. Soon he is the only character on stage and just before the lights are out, he turns to the audience and smiles mischievously. Despite uneven acting, especially a throw-away performance by Rufus Hound as Jack Cade, the middle part of the trilogy is worth seeing as it is a standalone piece of great dramaturgy by John Barton.

The Painted Devil

Richard III, the last play in The Wars of the Roses, is the weakest in the trilogy and it provides a kind of anti-climax to the engaging Edward IV under Nunn’s direction. It is perhaps because it is a well-known, often performed play and requires original staging ideas. The narrative is quite simple too: Richard, Duke of Gloucester kills all his family, opponents and friends in the quest for the English crown. He is the devil incarnate, without conscience and soul. Fortunately he ultimately fails and is killed by future Henry VII, the founder of Tudor dynasty.

Sheehan provides an audacious but enjoyable caricature of the murderous Richard. Instead of morose, shrewd and mature prince he gives us a youth with a violent streak, who is expressive and energetic, mischievous and rash, adolescent and compulsive. When watching Sheehan perform you get an impression that he has too much fun with the part and he does not care whenever he overacts. As a result he fails to achieve any gravitas even when facing death and is a peevish presence even in the conclusion. The tragic dimension of the play is saved by Alexandra Gibreath as Queen Elizabeth and Joely Richardson who shines in the production as aged, Hecuba-like Margaret. Ultimately what should be an exciting, visceral narrative is marred by slow pace, lack of original staging ideas (lots of repetition especially in the depiction of the battle scenes with the use of strobe lighting) and clunky acting. Some of the finals scenes are simply dreary: the rise of Henry Tudor is staged like a school play or an intentional piece of propaganda: it is hard to decide if it is a satire or bad acting. Only Sheehan’s portrayal of Richard III is worth seeing in this otherwise very patchy production.

We have come far when it comes to adapting history plays in the UK: from Kenneth Branagh’s nuanced and not always sympathetic portrayal of Henry V and the battle of Agincourt in his famous 1989 film to Propeller’s 2001 Rose Rage, an adaptation of Henry VI 1-3 plays which conveyed true menace and visceral quality of the Medieval power struggles in the English ‘game of thrones’. Nunn’s staging of The Wars of the Roses trilogy is a missed opportunity to adapt a great script of John Barton into productions that can stand on their own in the twenty-first century theatre.