Zhang, a native of Shanghai, received his undergraduate degree in 2000 from Shanghai Jiao Tong University and his Master of Fine Arts in 2008 from Shanghai Theatre Academy. Since the age of twelve, he studied Kunqu (Chinese: 昆曲), which is one of the oldest surviving forms of Chinese opera. He has served as a professional Kunqu actor in the Shanghai Kunqu Opera Troupe for eighteen years.

Zhang has devoted himself to introducing the kunqu operatic tradition to audiences, in particular to young people, throughout China and abroad. Since 1998, he has organized over 400 interactive performances that focus on young audiences and has lectured in high schools and universities in both China and the West.

Zhang Jun has been officially ranked as one of the leading performing artists in China today. In 2011 he was nominated as a UNESCO Artist for Peace in recognition of his long-term commitment to promoting the art of kunqu opera and for his “long-term commitment to promoting intangible cultural heritage, especially Kunqu Opera.”

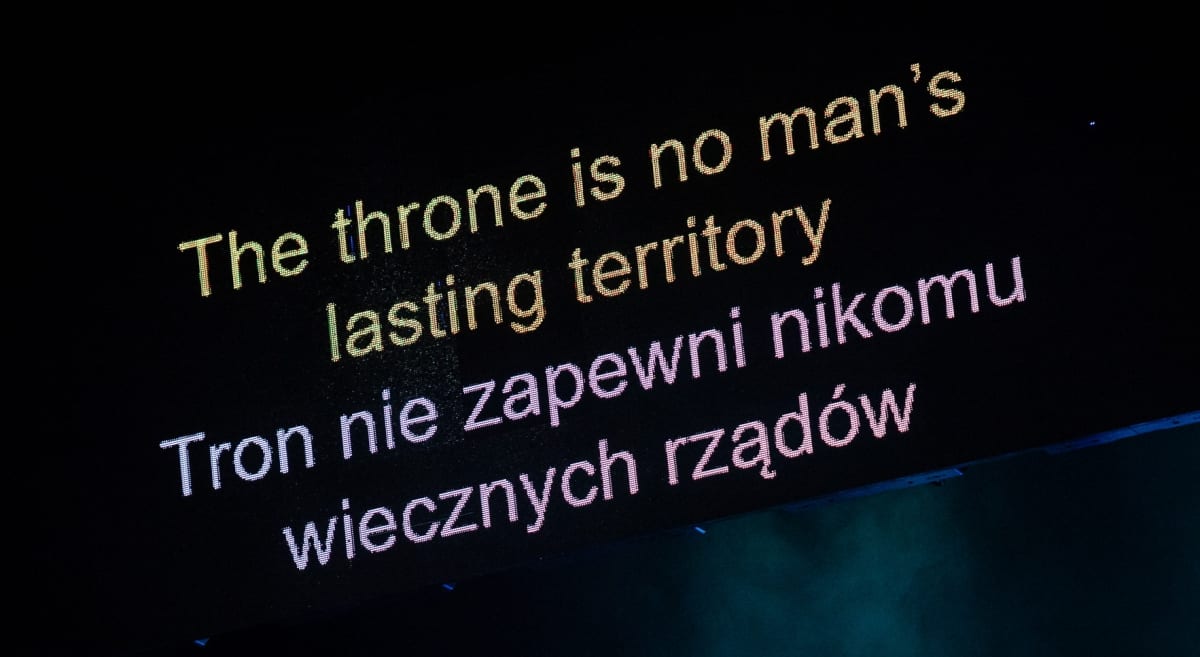

We met at the magnificent Gdansk Shakespeare Theatre on the splendid occasion of Chinese Culture Week in Gdansk, which opened with Zhang Jun spectacular staging of ‘I, Hamlet’ in October 2018.

Zhang Jun’s solo performance is remarkable, to put it mildly. The versatility of his acting, dancing, singing and delivering different roles in the edited version of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, is simply dazzling.

Zhang Jun’s solo performance is remarkable, to put it mildly. The versatility of his acting, dancing, singing and delivering different roles in the edited version of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, is simply dazzling.

He is measured, yet enthusiastic. Music and singing seem to be part of his DNA. He sings a note to make a point and enthusiastically shows me his video of himself as a Rock n’Roll star singing Queen’s ‘We Will Rock You’ in front of what looks like thousands of teenagers in China. He can perform the traditional Chinese opera and also Western-style popular music.

Zhang Jun founded his independent company nine years ago. According to Zhang, it is the only theatre company in China that is not subsidised by the government. He admits that prior to setting up this company, he acted for a state-funded theatre, but for personal reasons, he decided to go independent. Government-funded theatre is restricted and subjected to censorship. With the independent company he has no doubt that he can air his own views.

“In the government-based troupes, they are quite mechanic. With my own group, there are more possibilities to create artistic productions such as ‘I, Hamlet’ he explains.

His version of the play, as a solo piece, is based on the principles and tradition of the Chinese opera, a form that the actor can create whatever he wants on the stage “I like the creative freedom that the form allows” he explains.

Unbeknown to many outside China, 2016 Shakespeare’s 400 anniversary coincides with China’s Shakespeare, Tang Xianzu. Shakespeare and Tang died in 1616. Tang, famous above all for the Four Dreams of Linchuan, the best known of the four being The Peony Pavilion (Mu Dan Ting). Tang’s works were originally adapted to be performed as traditional Chinese operas ( Kunqu). This inspired Zhang Jun adaptation of Hamlet to fit into a Chinese format, fusing Shakespeare and Tang, East and West, in this exquisite production of ‘I, Hamlet’.

Unbeknown to many outside China, 2016 Shakespeare’s 400 anniversary coincides with China’s Shakespeare, Tang Xianzu. Shakespeare and Tang died in 1616. Tang, famous above all for the Four Dreams of Linchuan, the best known of the four being The Peony Pavilion (Mu Dan Ting). Tang’s works were originally adapted to be performed as traditional Chinese operas ( Kunqu). This inspired Zhang Jun adaptation of Hamlet to fit into a Chinese format, fusing Shakespeare and Tang, East and West, in this exquisite production of ‘I, Hamlet’.

Zhang explains the two basic principles of Chinese opera – a combination of dancing and singing which sustains the second important principle, namely, incorporation of cultural symbols.

The space on stage, in Chinese opera, is usually represented by vanity, nothing else. Then the characters represent themes – Hamlet’s father embodies vengeance, Ophelia, the theme of love and the play is a dialogue between life and death, and the question of To Be or Not to Be, is at the centre of the dialogue. So eventually, we present the entire concept through dancing and singing on stage.

In this production, the stage is filled with chairs, skulls and, there is even, as a centrepiece, a sarcophagus. Zhang explains that the set it wholly created by Wang Huan, the company’s young artist. He studied at the Central St Martin School of Art in London and was the first Chinese student on an MA course at RADA. “He created the chairs and puppets that transformed the stage to act as a place between the past and the present”.

The audience in Gdansk impressed Zhang. It’s very different from the Chinese audience, which prefers to watch a story on stage. This sort of performance, based on philosophical dialogue and, thesis and antithesis, is more difficult for the audience in China. For example, in the post-performance Q&A in Poland, it was extremely interesting that they could discuss and understand this different form of Shakespeare. A member of the audience summarised the very essence of the play in one word, ‘contradictions’. The contradictions in life are exactly what we want to communicate with the audience. In China, there are three particular philosophies: Confucius, Buddhism and Taoism. So, we ask the question, what is life and death among these three perspectives that are melded in Chinese culture? In Shakespeare, there is a quotation about springtime and the arrival of autumn. We translated part of the script into our play to say that ‘Only in the theatre and the tomb can we talk about death’. Death is a topic that we tend to avoid talking about in our everyday life.

The audience in Gdansk impressed Zhang. It’s very different from the Chinese audience, which prefers to watch a story on stage. This sort of performance, based on philosophical dialogue and, thesis and antithesis, is more difficult for the audience in China. For example, in the post-performance Q&A in Poland, it was extremely interesting that they could discuss and understand this different form of Shakespeare. A member of the audience summarised the very essence of the play in one word, ‘contradictions’. The contradictions in life are exactly what we want to communicate with the audience. In China, there are three particular philosophies: Confucius, Buddhism and Taoism. So, we ask the question, what is life and death among these three perspectives that are melded in Chinese culture? In Shakespeare, there is a quotation about springtime and the arrival of autumn. We translated part of the script into our play to say that ‘Only in the theatre and the tomb can we talk about death’. Death is a topic that we tend to avoid talking about in our everyday life.

Zhang performs Ophelia. To explain her character he says, “The distance between Ophelia and the father is quite evident. Ophelia is a source of consolation for the spirit of Hamlet. The father is represented by vengeance. The important question is how could Hamlet choose between them? In his process of hesitation, he himself walks towards death”.

He pauses for a moment, looks at the interpreter and with renewed enthusiasm he adds, “our interpretation of Hamlet plays on the diversity of themes within the play. The principal point is the conflict between the characters. I would like the director to present the question to be or not to be, the conflict within this question is hesitation. Of course, when it comes to the father, there is also a conflict between the past and the future. Eventually, the important point, as the director emphasises, is the disorder that is hidden within the play”.

RJ: Does it reflect today’s society in China, or society in general?

ZJ: This is an art form that has 600 years of history. We have to choose whether we let it be presented in museums as a dead art, or we have it live on stage to communicate with youngsters. I have been working in this field for more than 20 years and the root of the art form remains unchanged but the contradiction that I confront is still there – Is it a reflection of myself in the society? This is a question that comes to my mind very often.

In this production, dance and Chinese opera are an inextricable part of the performance. Zhang explains that hours of training every day are absolutely crucial to master this complex art form. “It is based on traditional techniques that we transform into different possibilities. In Chinese opera, every aspect, such as sound, costume and gesture, is strictly defined. It has hundreds of years of history, and ever since we were young we are trained within these rules. The first stage is mechanical training, the second phase is the training of concentration, and then the third is how to communicate with your mental wheel. It’s learning how to connect every technique you train in with your inner self”.

Not only can Zhang act superbly but he can also amaze by his dance and vocal performance. He explains that in traditional Chinese Opera, each melody is based upon a pre-made form. “Every transformation or iteration has to be based upon a form. Even in I, Hamlet, it is a challenge to compose whilst following and respecting the set form”.

Zhang Jun, it was a great pleasure and an honour meeting you and seeing you perform.

Very special thanks to Katie Dow who kindly transcribed the recorded interview.