Agrigento, a city steeped in history and culture, paid homage to one of its most illustrious sons, Luigi Pirandello, on the 157th anniversary of his birth.

This year’s celebrations, held on June 28, 2024, highlighted the enduring legacy of the Nobel Prize-winning playwright and novelist, whose works continue to captivate audiences worldwide. The festivities were a vibrant mix of theatrical performances, scholarly discussions, and community events, all designed to honor Pirandello’s contributions to literature and drama.

The streets of Agrigento were transformed into a living tribute to Pirandello. Banners and posters adorned buildings, showcasing famous quotes and scenes from his works. The city’s theaters, museums, and cultural institutions collaborated to create a program that both celebrated Pirandello’s achievements and engaged the local community.

Central to the anniversary celebrations were theatrical performances that brought Pirandello’s complex characters and thought-provoking themes to life. The premiere of “Tararà,” staged at the theatre Il Circolo Empedocleo in Agrigento, Sicily, directed by Mario Gaziano, was particularly noteworthy. This adaptation weaved together elements from Pirandello’s novella “La verità” and his plays “A birritta cu i ciancianeddi” and “Il giuoco delle parti.” The inclusion of English surtitles, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Impact Acceleration Account, enabled non-Sicilian-speaking audiences to fully appreciate the nuances of Pirandello’s Sicilian dialect and the depth of his philosophical inquiries. The performance was a testament to Pirandello’s enduring relevance and the innovative ways his work can be made accessible to diverse audiences.

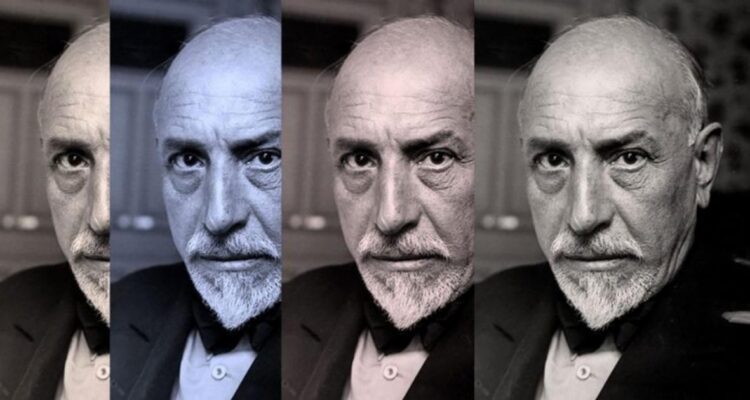

Giuseppe Gramaglia a lead actor in Pirandello’s “Tararà”

I’m retired now and theatre is my hobby, my passion. I’ve been acting for about 22 years in different theatre companies. In recent years, my focus has been on the works of Pirandello, as I am part of the Pirandello Stable Festival theatre company directed by Mario Gaziano here in Agrigento – Pirandello’s birthplace. Each season is dedicated to staging Pirandello’s plays, and this year we performed at the Circolo Empedocleo. We have such a huge following that it’s often hard to accommodate everyone in the theatre.

How did you become involved with this production?

I was invited to take part in “Tararà” by the director, Mario Gaziano. The first part of the play, translated into Sicilian, is based on the novella “La verità” and centers on the main character, Tararà, who murders his cheating wife not out of jealousy but because of the inexorable ‘eye of the people’ who see and know of her betrayal. He must, therefore, inexorably kill her, shouting in a conflicted and feverish manner: “Signor iudici iu ci vuliva beni” (‘Your Honour, I loved her’). The second part is based on “A birritta cu’ i ciancianeddi” (1916), a Sicilian version of “Il berretto a sonagli,” where Pirandello expands “La verità” by adding the character Ciampa, who explains the madness behind his murderous actions using Pirandello’s ‘philosophical-speculative method.’ The final part, translated from “Il giuoco delle parti” (1918), focuses on il perno (the pivot), an imaginary nail that distorts reality, reflecting Pirandello’s own explorations of art, form, appearance, and reality.

How did you feel having surtitles follow your live performance?

This was the first time I had ever worked with surtitles, and it was a very interesting addition to the performance. The surtitles certainly helped to welcome a wider audience, which I found beautiful. They are particularly advantageous for tourists who don’t understand Sicilian. Additionally, surtitles can help circulate Pirandello’s works abroad, conveying the essence of his theatre to international audiences. His theories about the mask and distinguishing reality from illusion are fascinating, though complex. Even in “Tararà,” the notion of living for the ‘eye of the people,’ being not who one is but who one believes oneself to be, is truly intriguing.

Did the use of surtitles cause you any problems? Did you identify any drawbacks?

What perplexed me was that actors are not machines and can never perform the same text in the same way each night. Actors add their own interpretation based on their feelings at the moment, which can affect synchronization with the surtitles. Despite this, the performance was understood perfectly. I found it astonishing that the surtitles, maneuvered manually rather than via special software, were in sync with the actors’ interpretations.

Finally, the play was in the Sicilian dialect. Could you say more about the artistic choice to perform in this language?

Learning that UNESCO classifies Sicilian as a ‘vulnerable language’ made me realize the importance of our work in Sicilian in two ways. Firstly, it’s crucial to convey Sicilian plays to international audiences via surtitles. Secondly, it’s essential to preserve our language for future generations. In Sicily, we often correct children who speak in Sicilian, pushing them to speak “correctly” in Italian. We need to find a balance between Sicilian and Italian. Performing this piece in Sicilian was also a way to help our younger generations retain their linguistic heritage and prevent our dialect from disappearing, like so many others around Italy.

* The surtitles were funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Impact Acceleration Account and supported by the Society for Italian Studies in collaboration with Glasgow University as part of the project “Translating Pirandello in Agrigento: City of Culture (2025),”