Writer Lesley Hart and director Polina Kalinina bring plenty of zest and visual panache to this ambitious production of Russian classic Anna Karenina. Their retelling sticks close to the original story of a woman who falls in love outside of her marriage, and is subsequently shamed and punished by the patriarchal society in which she lives. Despite its origins nearly 150 years ago, the duo have no difficulty in highlighting the contemporary resonances of a society that values a man’s sense of honour over a woman’s happiness and self-determination.

The story has an inherently theatrical quality to it (something also effectively mined by Tom Stoppard in his 2012 adaptation for the screen) and even features a key scene set in a theatre. Hart and Kalinina effectively riff on this in their production, drawing out themes of watching and being watched throughout. Occasionally, the cast address us directly, inviting us to participate in the spectacle of Anna’s downfall. Urgent, gossipy whispering comes and goes on the soundtrack, as the reputations of Anna and those around her are dissected by society.

Of course, it is Anna’s reputation that suffers most of all, purely by dint of her being a woman. The male characters are able to carry out affairs and generally misbehave without attracting anything like the same moral opprobrium. The women, meanwhile, must put up with their philandering husbands, and are confined, silenced or restrained if they try and exercise their own agency. The production clearly highlights the contemporary parallels with a sexist society that still disadvantages women, that still applies misogynistic double standards.

This is most obviously done through the adaptation of the text, although the staging plays its part too. Female characters are taken to task while scenes of male characters avoiding responsibility for bad behaviour play out at the same time, laying the double standards bare. The sense of impending doom is effectively, if a little obviously, conveyed through a rotating spike, hanging ominously above the head of Anna as her life spirals out of control. Some clever staging separates the town scenes from the country, although it occasionally obstructs and limits the performances. It also forces an over-reliance on amplification for the actors, throwing up a barrier between cast and audience.

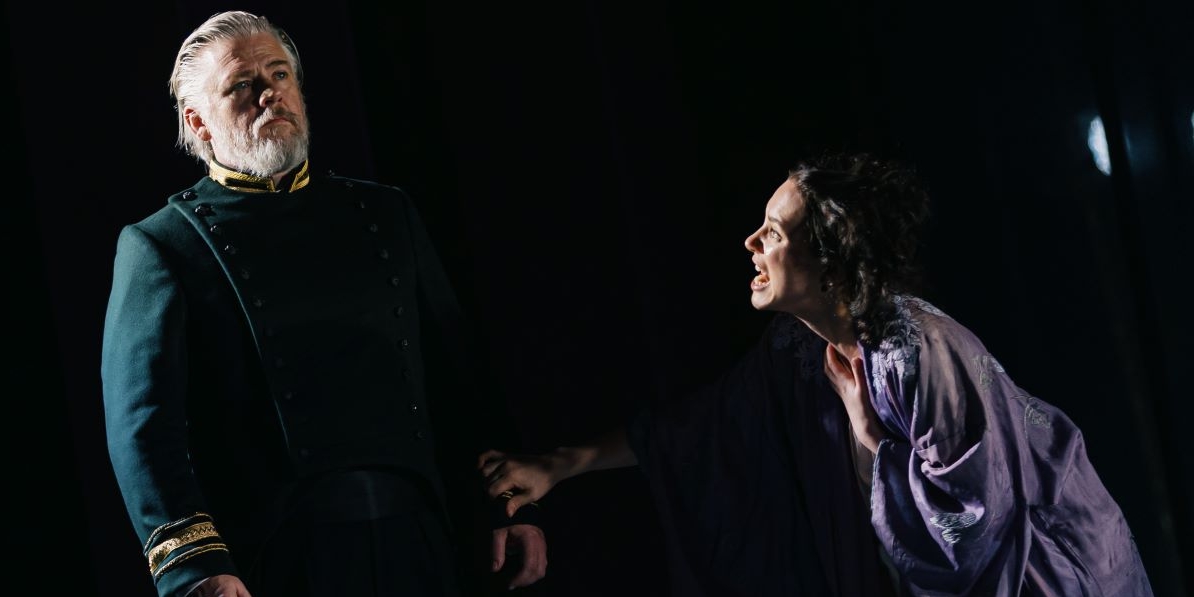

Nonetheless, the chemistry between the actors still manages to sparkle. Jamie Marie Leary is superb throughout, and her furious, wounded scenes as Dolly with husband Stiva (Angus Miller) are a treat. Ray Sesay elicits considerable sympathy with his depiction of the often lost-seeming Kostya, while Stephen McCole even manages to bring some relatability to the cold and cruel Karenin. The play belongs, of course, to Lindsey Campbell as the titular character. Her Anna bears the weight of the whole production on her shoulders, and she physically embodies her character’s arc from confident society woman to bowed and broken end.

If the final scenes feel a little rushed, the last actions of the characters a little under-motivated, then this is perhaps an understandable consequence of trying to cram 239 chapters into a little over

two hours. Hart and Kalinina have largely done an excellent job of interpreting this sprawling story, and they let its contemporary resonances ring out loud and clear.