Iddo Netanyahu is a physician, author and playwright, whose plays have been performed in Israel and beyond.

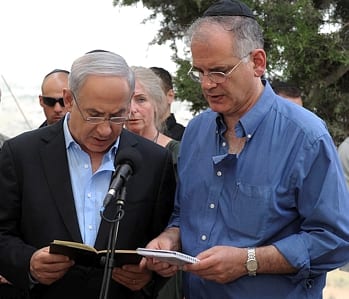

The Netanyahu family is well known. The father, was a professor of history; the late eldest brother, Jonathan, was a lead-commander in one of the most daring rescue operations in modern history, Operation Entebbe (renamed Operation Yonathan), in which over 100 hostages held at Entebbe Airport in Uganda in 1976 were rescued and in which he lost his life at the age of 30. The middle brother Benjamin is the current Prime Minister of Israel.

Iddo is well spoken, relaxed and rather charming. His voice and accent echo that of the Israeli Prime Minister, but with slightly softer and warmer tones.

Although he was trained as a physician, he devoted much of his time to writing short stories, novels, and non-fiction – that is, until ten years ago when he found himself gravitating towards drama. ‘Ever since then, apart from the occasional article, I’ve been writing only plays’, he says with a touch of meditative look. He has written six plays so far, three of which have been performed and a fourth scheduled to premiere next year in Italy and Germany. “It’s a comedy called The Muse”, he says. “Bacchus comes down from Olympus to attend a 21st century ‘Bach and Bacchus’ music-and-wine festival. Jupiter has been threatening to downgrade Bacchus’s godly standing because of his constant frolicking, and Bacchus decides to summon the great composer Bach from his home in Leipzig. He demands of Bach that he teach him – the quick and easy way – how to become someone profound, able to produce great art. It’s a farce about how we regard modern-day artistry. I am curious to see what they’ll do with it”.

Iddo finds it fascinating to see how audiences respond differently and how dissimilar the productions are in various countries. He adds ‘The interpretation is always very surprising – some things you agree with, some you don’t. If it’s a great director, it’s a pleasure’.

The narrative in some of his plays is set against a factual historical backdrop. Such is Iddo’s first published and performed play, A Happy End, which takes place in Berlin at the end of 1932 and early 1933. It is set against the backdrop of the rapidly changing atmosphere in Germany, around the time of Hitler’s rise to power and the inability of some middle-class educated Jews to read the writing on the wall.

The main protagonist is a leading physicist whose world is embedded in resolving scientific problems. Netanyahu draws delicate lines of increasing harsh developments in an attempt to convey the reality as seen at that period. Love and betrayal unfold in an uncomplicated narrative that gnaws into the core issue of why intelligent Jews failed to understand what’s happening around them and leave, even when offered a reasonable alternative to life in Germany. ‘The audience knows that if they don’t leave, they will end up in the gas chambers. But the characters don’t know that of course. Seemingly, nobody knew that in 1932, 1933’, Netanyahu explains. A Happy End was first performed in Italy and later in Israel by Beit Lessin Theatre in Tel Aviv. It then made its way to Abingdon Theatre in New York and other American theatres, as well as to Central Asia and Eastern Europe, mostly in Russian translation.

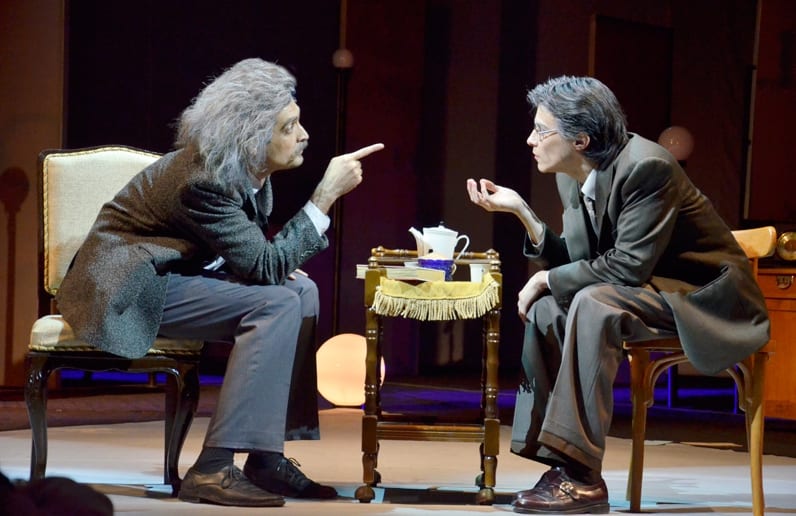

Netanyahu’s second play Worlds in Collision has at its core meetings between Albert Einstein and Immanuel Velikovsky. The very name of the play is based on Velikovsky’s book of the same title. Iddo explains that ‘this is the struggle between Immanuel Velikovsky, who believes that he found tremendous insight, with his revolutionary theories about the universe and cosmic events and human history, and the scientific world that was against him. The play is based on a true story. Velikovsky was thoroughly castigated and branded by the scientists a charlatan and liar, and his one last hope of redemption was Albert Einstein whom he tries to convince that he is correct in his theories. In some ways, it’s a play about the quest for ultimate knowledge, both by Velikovsky and by Einstein. Is it at all possible to attain? And in what way does public recognition, or conversely severe rejection, play into all this?”

RJ: Jews are your main protagonists.

Iddo Netanyahu: Although the two characters in this play are Jewish, it’s not really to do with Judaism. Except for maybe a constant need to understand the world”. The play was first performed in Russian in 2015. “I haven’t written many plays; only six so far. Out of these, I’ve submitted four, and I’m very happy and very lucky they’re all being performed or about to be. The other two are still in draft”.

He writes in Hebrew and translates his plays by himself into English. His official Russian translator translates them into that language from Hebrew.

What is the next play that’s about to premiere? I asked.

“Meaning, which will have its Azerbaijani premiere in a few weeks at the Mugam Center in Baku, and then shortly afterwards will premiere also in Moldova. The play has already been beautifully done by Blagoj Micevsky at the Bitola State Theatre in Macedonia. It’s about a famous psychiatrist, Viktor Frankl, who wrote this book, sort of a memoir about the concentration camps and his search for meaning there. He had a theory about how to overcome psychological ailments by finding meaning in one’s life. This is something which I think we all accept, but Frankl went much beyond this and believed that his brand of psychology will actually heal mankind and solve the world’s problems. The conflict in the play centres on this utopianism versus a more concrete view about life, that’s by its very nature less optimistic. The story goes back and forth between the concentration camp and Frankl’s clinic in Vienna fifteen years later, where he is treating a woman whose child is suffering from anti-Semitic persecution in school. Although it’s based on the persona and thinking of Viktor Frankl, it’s a totally fictional work. You asked about Jewish themes in my works? So yes, once again there is a Jewish theme here related to our past. But in fact, like my other plays, it has to do with what’s happening in the world today.

RJ: Should plays mirror something of current reality?

Iddo Netanyahu: I’m not sure ‘mirror’ is the term I would use. But I cannot imagine any playwright or author writing anything that doesn’t relate to his times, to his being involved with society, with what’s happening in the world or his own country. This play that I’m now working on takes place in medieval Spain, more than 600 years before our time, but in fact, I’m writing about the social reality of today, things that I believe are fundamental to our existence as a society and to the individuals in it. To what extent and how is it relevant? Let the audience decide in what way it thinks it pertains to today, if at all.

RJ: None of the four plays mentioned confronts any of the current issues that Israeli society is grappling with. Why?

Iddo Netanyahu: As I’ve already alluded to, I believe they do – in fact, very much so. Maybe I chose to place events in the past and outside my country for the same reason numerous playwrights have done so before me, finding that if you take the audience far away from the turmoil in which they are currently embroiled, they will be more receptive to what the play has to say.

RJ: Does the fact that your brother is the Prime Minister of Israel affects your open approach to addressing current conflicts within the country?

Iddo Netanyahu: No, his being PM doesn’t affect me. But if by “open approach” you mean writing a play that is a sort of political or social pamphlet disguised as a piece of drama, this is not my kind of play-writing. For sure, politics in some form or fashion is present in my plays, but it has to be gleaned from the contents. As a rule, I dislike plays that openly espouse a political, social or ‘behavioural’ message. It’s usually a simplistic kind of writing which tries to appeal to people’s already formed views, and is nearly always boring, at least for me.

RJ: Do you find that your brother’s political views help, overshadow, or affect you in any way?

Iddo Netanyahu: No, they don’t affect me or my writing. But I can assure you that they very much affect the way some people choose to regard me and my works. In Israel, I’m currently not being produced. I cannot say what is the reason for this, whether it’s based on prejudice due to politics or whether it’s due to other reasons. But it doesn’t really matter, since, politics or not, I’m pretty certain that it’s just a matter of time until my plays will be staged in Israel as well. I see the reaction they have on audiences and I see various critics’ reactions. Eventually, I’ll be produced here as well. And you know what? It could also be that my plays don’t quite fit the general Israeli taste. That might be a factor here. But then, what of it? A play doesn’t have to fit all tastes. God forbid that it does. But it can to appeal to some, not all.

RJ: Don’t you think that the political scenario has any part in that?

Iddo Netanyahu: As I said, I don’t know. But let’s see what happens down the road. Truth is, I am not complaining at all. My plays are being shown in quite a few places, they are well produced and are staged by some great directors and acted by fine actors, and so I’m happy. Surprised too, to be honest.

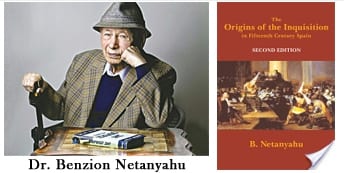

RJ: Your father was a historian who specialised in the period before the Inquisition. Has that affected the way you perceive history and the issue of the rise of anti-Semitism?

Iddo Netanyahu: I learned a lot from him with regards to history in general, and to anti-Semitism in particular. His magnum opus, The Origins of the Inquisition, contains a brilliant introductory chapter that examines, and I believe answers, the difficult and age-long question of anti-Semitism, how it was born and why it spread throughout Europe and beyond – in short, how it turned into the terrible plague that has been ailing human society for generations upon generations.

With regard to the current wave of anti-Semitism, I see it as part of a never-ending cycle which started, as my father pointed out, in Egypt long before Christianity and which has been around for well over two millennia; it waxes and wanes according to social, economic and historical conditions and events, but is always there. You can try to fight it, and sometimes you might succeed in persuading some people to change their minds about the Jews, but that’s no solution for the Jews. The only solution is the one that modern Zionism developed back in the 19th century. The founders of Zionism understood that the Jews need to move to a country of their own and create a military to defend themselves. Because the problem of the Jews was not only that they were reviled by the populations at large, but that they were powerless to physically defend themselves against the numerous attempts to destroy them and banish them, which as you know often succeeded. Now, with Israel existing, at least the millions of Jews who live here have the ability to defend themselves and live their lives.

“But going back to my father’s writings, the very first play I wrote, which takes place in Medieval Spain, was inspired by an article of his. It is about the grandfather of the famous Jewish leader during the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, Yitzhak Abravanel. They were a remarkable family, the Abravanels. All of them were leaders of the Jewish people in Spain. This grandfather, Don Samuel Abravanel, was THE Jewish leader of the Spanish Jews and their great defender against powerful enemies. But it turned out that he then converted to Christianity. The question is, why did he convert? What happened there?

So when I read my father’s article, the thought came to me that it’s a very dramatic story that touches upon Don Samuel’s struggles between his loyalty to his people and his wish to punish them, combined with his aspiration for greatness. ‘This really should be a play’, I said to myself. And that’s what got me started writing plays. It was my first play and it was not written well enough, for obvious reasons. Thankfully, it was rejected at the time – yet from there I started my career as a playwright. But I very much believe in this particular play and I am now busy rewriting it.

RJ: How easy it is for you, as a physician, to delve into your characters’ mind and emotions?

Iddo Netanyahu: As a writer, it’s something you need to know how to do, whether in your other life you happen to be a physician or, I don’t know, a barista. Writing anything involves psychology. You have to delve into people’s minds, try to understand them, and combine all that with the plot, the conflicts, your underlying ideas, and in doing all this try to gain at least a glimmer of understanding about humans and their society. As you probably know, many famous authors were physicians, like Chekhov, Bulgakov and others. Jews too. The famous philosopher Maimonides was a physician, for instance. But then, among Jews, being a physician is very popular, and maybe that’s the reason there are so many physicians among the Jewish writers.

You ask what do I try to do in my plays? Well, I know what I don’t try to do. I don’t try to do what I don’t like, which is, first of all, obscurity for obscurity’s sake. I simply don’t like unintelligibility. I see no point in it. I’m not referring here to writing that might be difficult to understand and requires mental effort. The audience might have to think long and hard about what they saw, and that’s fine. In general, though, things should be comprehensible on some level, otherwise, the piece is simply unapproachable to the human mind and consequently also to the human heart. Unfortunately, intentional obscurity has been a prevalent feature in the arts for a long time now.

I also do not like declaratory theatre. This is a disease of the West, this blaring out with a bullhorn your brilliant, inspiring and righteous political or social stands. Theatre has become in many instances explicit rather than implicit. But ‘implicit’ is the beauty of art. And I’m not talking here necessarily about politics or saying that playwriting cannot be political. No matter if it is or not, it should be done in a way that would make people try to understand things for themselves. Challenge the audience! Don’t preach to them. Don’t just tell them what they should be thinking and what opinions they should adopt.

RJ: Your plays are successful in some ex-Soviet Union countries. Can you explain that?

Iddo Netanyahu: So far, I’ve been successful in other places as well, such as off-Broadway in New York, and the audience there is quite different from that of the Eastern European countries. I think it’s just happenstance that my plays are circulating today mostly in Eastern European countries.

Netanyahu is open to constructive comments. “I learn from actors. On a certain level, they may understand the characters better than the playwright since they’ve spent so much time with them; they have literally ‘lived’ them. Occasionally they suggest adding or deleting certain lines, and you’d be an idiot not to take their comments seriously. One of the reasons I initially wanted to be in rehearsals was in order to better understand the craft of theatre because I knew I was a novice in these things. I still consider myself a novice and am still trying to learn. So being part of the rehearsal process is very helpful”.

RJ: Should theatres be subsidised?

Iddo Netanyahu: In my opinion, no. But not only theatre. Art, in general, should not be subsidised. The very fact of subsidisation via a committee, often politically or socially motivated, consisting of a group of usually like-minded people who decide who and what gets to be shown, is ultimately a form of control that has nothing to do with art. In Israel, when it comes to theatre or cinema, these subsidies do not allow for independent productions since such productions become virtually impossible. What Israeli film producer would give his money to a movie that doesn’t get half its budget from one of the two public committees that decide? Why should he take the risk of losing his money? So in the end, these subsidies limit artistic expression. Look at the great movies of Hollywood of the past, or the great productions of the West End – no committee of bureaucratic ‘experts’ gave them any public subsidy, yet great art was produced in those places.

Iddo Netanyahu, it was a great pleasure talking to you.

My special thanks to Austin Fimmano for transcribing the interview.