Canada is 150 years old, and we celebrate this nation’s many evolutions with carefully commissioned works of art and culture in a grand festival that lasts throughout 2017. The COC’s restaging of Harry Somer’s Louis Riel (1967) was, no doubt, meant to be a celebration of history, music, and culture; but it is in precisely these aspects that it fails. Miserably.

To our international readers who may be less familiar with Canadian history, Louis Riel was the founder of Manitoba, and arguably, our most recognized Métis revolutionary and leader. He was our Ché. Any grade seven child would tell you of his great resistance to British colonial rule, and his unfailing efforts to force the Crown to recognize Indigenous rights. We also know that Riel was a flawed figure, with his own share of delusions of grandeur, but to portray him as a God-obsessed megalomaniac mamma’s boy is to frame one of the most important characters of Canadian history within a rather narrow lens that does him no favours. Perhaps the librettist, the famed Mavor Moore, only wished to bring a complexity to Riel, and to make him more man than hero, but the result is a character whose motivations are unclear, and who seems to blow any which way his mother, or God, wishes him to go.

The music, which was composed in 1967, promotes a particular brand of atonality that makes for chaos. Somers, who studied with Darius Milhaud, among others, was knighted by Canada before I was even born, but to call this opera a work of genius is a case of the emperor’s new clothes. According to Réa Beaumont’s program notes, the work combines tonal, atonal, electronic and pre-recorded sounds, as well as folk elements including songs from Métis and Indigenous cultures. It is the latter that renders the work most problematic in its attempts to represent indigeneity.

Dylan Robinson, Wal’aks Keane Tait, and Goothl Ts’imilx Mike Dangeli, the cultural advisors to this evening’s production, outline some of the pitfalls associated with the work’s most lyrical aria, the “Kuyas” aria, which is sung by Marguerite Riel, Louis Riel’s young wife. In their words, “… The ‘Song of Skateen,’ a Nisga’a mourning song, was used by Harry Somers without the knowledge of Nisga’a protocol that dictates that such songs must only be sung at the appropriate times, and only by those who hold the hereditary rights to sing such songs.” I do not see any mention in the program notes that Soprano Simone Osborne, who plays Marguerite Riel, is Nisga’a, and although her performance was guided under a production team that included Nisga’a, Métis, and other Indigenous community members, one has to return to the words of the advisors as they note, “To sing mourning songs in other contexts is a legal offence for Nisga’a people and can also have negative spiritual impacts upon the lives of singers and listeners” (Robinson, Tait, and Dangeli, Louis Riel Program Notes, 2017). How can this be anything but cultural appropriation?

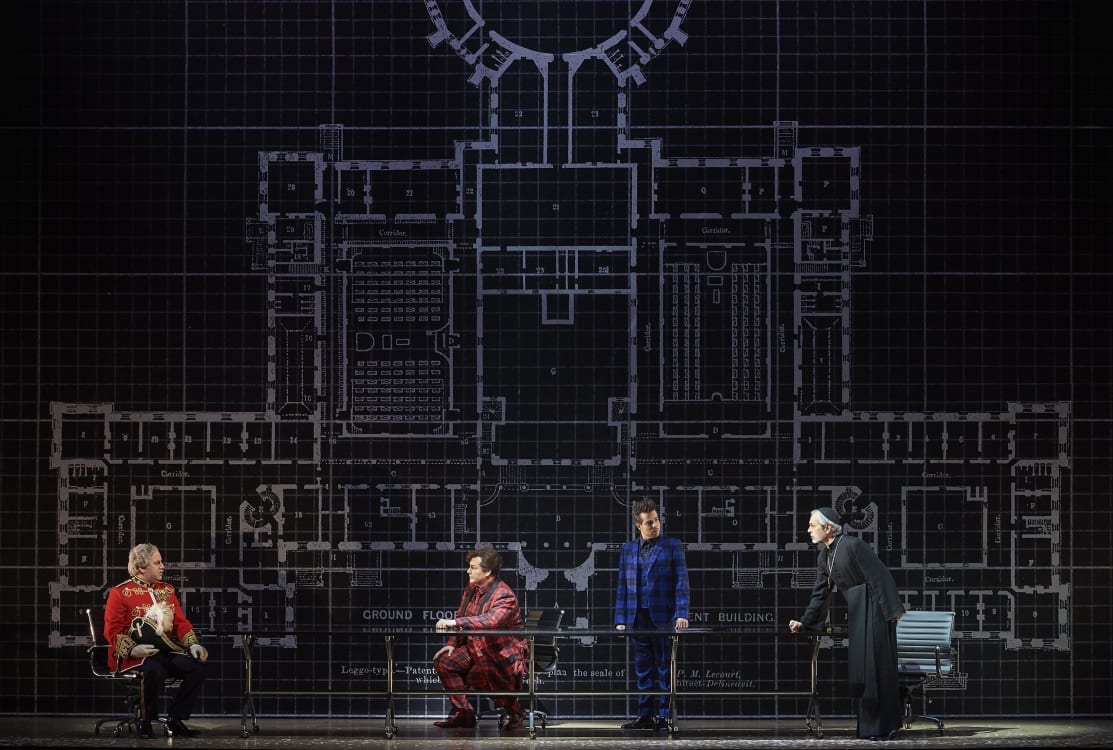

It would have helped, perhaps, if Ms Osborne’s two tone vibrato hadn’t completely masked any semblance of a line that might originally have sounded like that of the Nisga’a in our ears. Baritone Russell Braun, continues to bring star power, and as Louis Riel, still finds a way to bring richness and pathos to his role. Alain Coulombe as Bishop Taché, and James Westman as Sir John A. Macdonald, brought drama to the stage, but were frequently singing in registers that were drowned out by the orchestra.

Against this usual fare, is the powerful echoing silence of the Métis and Indigenous cast members who circle the stage in a silent chorus. These are the performances worth watching. And when Métis performer and singer, Jani Lauzon, calls out across the space, her voice will electrify you to your core. Lauzon also chants and raps, as Justin Many Fingers leaps and roars movement across the stage as the Buffalo Dancer; together with the chorus, they produced the only moments of dramatic power in the entire evening.

Somer’s Louis Riel has been around for 50 years. None of the issues I have outlined in this review can come as surprises. In a celebration that must also acknowledge the systematic cultural erasure of the Indigenous peoples of this land, and their rights which have been stolen, why stage the work of two dead white men who, albeit with good intentions, did little more than appropriate what was not theirs? In a year that is meant to be a celebration of history, why return to narratives that gloss over Indigenous and Métis experiences and cultures in favour of highlighting, yet again, age-old settler battles between anglophone and francophone Canada?

I can’t help but feel that an opportunity was lost here to commission an original work by an Indigenous artist. Canada has incredible Indigenous and Métis artists like Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, whose audio tracks to Islands of Decolonial Love (2013) will make you weep; but it was not their music, their words, or their stories that took the stage tonight.

The questions remains: Why this work? Why now? And I can find no legitimate answers.