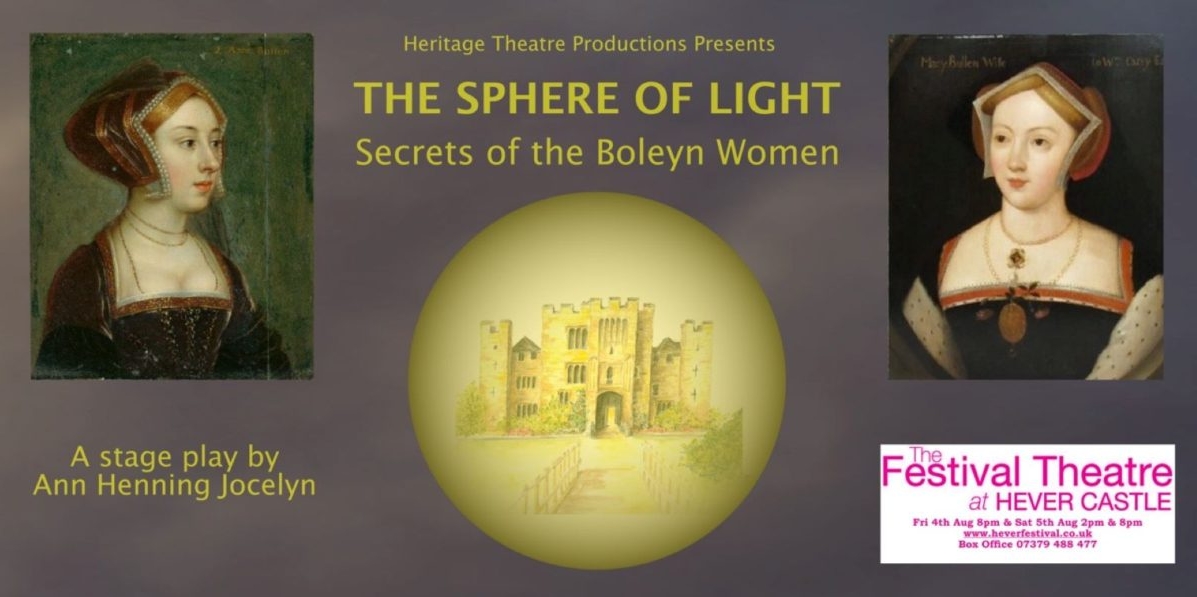

Hever Castle, childhood home of Ann Boleyn, hosts a theatre festival every year, and it therefore is a natural ambience for Ann Henning Jocelyn’s new play devoted not just to Ann, but also her sister Mary and sister-in-law Jane. This is hardly new territory, of course, and after Hilary Mantel and Alison Weir and the films and plays that have flowed from their books, is there room for more? Actually, there is.

In this play and the book from which it derives Jocelyn focuses on two individuals left on the sidelines or wholly omitted from previous accounts of the intrigues at the court of Henry VIII in the 1530s. The first is Lady Rochford, sister-in-law to Anne Boleyn, who gave evidence to Cromwell that led to the downfall and execution both of her own husband and the Queen. The second is a mysterious George Boleyn, a clergyman of the next generation, who may, on some readings, be the son of Lady Rochford and her husband. The play offers a solution to why Lady Rochford turned on her relatives and why George, if he was indeed her son, remained unacknowledged. We are invited to imagine that all the participants are reunited in ‘the sphere of light’ after death and compelled to give George, in particular, answers to the many questions he has.

It is an engrossing story, and Jocelyn deserves credit for finding a lucid structure in which to unravel it once more, getting the balance right between the complexities of family and court politics under Henry VIII and avoiding over-elaboration with too many layers of intrigue and subterfuge. The characters are well developed and the politics is broken up with bawdy irreverent ballads showing how unillusioned the populace were about the goings on at court. The pace is perhaps too leisurely – after all Mantel was onto something when she told the events of Ann Boleyn’s downfall as a short breathless thriller. However, given the difficult circumstances of the performance the actors did a fairly heroic job in getting their work across to the audience.

Last month a branch demolished the usual tented structure that houses the Hever theatre. So this production was then relocated to the loggia of the Italian garden instead. On a fine day, with sweeping views over the lake and the collection of sculpture assembled by William Waldorf Astor this would be a delightful, even distracting experience. But on a windswept day of continuous rain it was a different matter, and one had to feel for the cast dressed in flimsy silks and satins contending against the results of our unseasonal jet-stream.

That said, there were some characterful performances: as the unrecognised and neglected George Boleyn, Julian Bird ranged from chirpy toddler through to gruff and disillusioned old age with skill. Kitty Whitelaw applied a slow burn to the role of the vengeful Lady Rochford, complacent and accepting to start with, and then coming into her own in the final scenes. Robert Madeley looked elegant and shifty as a her husband and provided a useful double-act as a balladeer breaking down the fourth wall. Sarah O’Toole demonstrated the bright, arrogant charm and edgy self-esteem we now familiarly associate with Ann Boleyn, the favoured, pampered daughter of an ambitious clan. Maud May quietly revealed the more appealing aspects of Mary Boleyn, former mistress of a younger, more attractive Henry VIII, and Elaine Montgomerie projected the forceful matriarch of the family, drawing on many years of acting experience.

Just as in the musical ‘Six’, Henry himself does not appear, but looms over the action as a capricious, unpredictable and malign presence. It seems entirely plausible that his main motivations throughout these crucial years in English history were not about religion or even lust but rather a determination to impose his will and defy his father’s low assessment of his potential as monarch. In showing how the political ultimately is both personal and familial this play reminds us of a central truth that does not change over time.