Samuel Beckett’s transformational and radical play, Waiting for Godot, is a key part of the global theatrical canon. Performed countless times around the world, this year it comes to the Lyceum Theatre at the Edinburgh Festival, to be performed by the Druid theatrical company.

Two tramps wait in a bleak landscape for Godot, who should have arrived yesterday, who might come today and, if not today, then almost certainly tomorrow. As they wait, Vladimir (Marty Rea) and Estragon (Aaron Monaghan) bicker and make up, discuss the Bible and eat carrots, filling the time any way they can. They are interrupted by Pozzo (Rory Nolan) and his slave, Lucky (Garrett Lombard). Eventually a boy (Angus or Finlay Alderson) comes and says Godot is not coming today. So much for Act 1. Act 2 is, in its essentials, no different. One suspects that were there an Act 3, 4 or 5, the same description could still be written.

Indeed, Waiting for Godot has famously been described as ‘a play in which nothing happens, twice’, but Druid do what they can to disprove that well-known quote, at least from a physical point of view. Throughout the production, Vladimir and Estragon hurl themselves about the stage, leaping and contorting themselves into all sorts of awkward looking shapes.

This may be an opportunistic choice as a result of casting two reasonably young men in traditionally elderly roles (just five years ago the roles were taken on by Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart when both were in their mid-seventies), but it brings out much of the absurdity in Waiting for Godot. This production draws its comedy a little less from whip-crack delivery then others, but Rea and Monaghan wring every bit physical humour they can from the script.

This works well through most of the play, although it does lead to a reasonably long running time, and occasional mis-steps, where the comedy undercuts more serious themes at crucial moments. Mostly though, it is executed so well by the two leads that it does not detract from the overall enjoyment of the play.

Indeed, the acting throughout is excellent. Nolan undercuts the frightening Pozzo with a dose of absurd humour, while Lucky is rivetingly played by Lombard. His exhausted, rubbed-raw figure immediately quietens the chuckling audience, who then seem on the verge of rising to applaud him at the end of the manic waterfall of his speech.

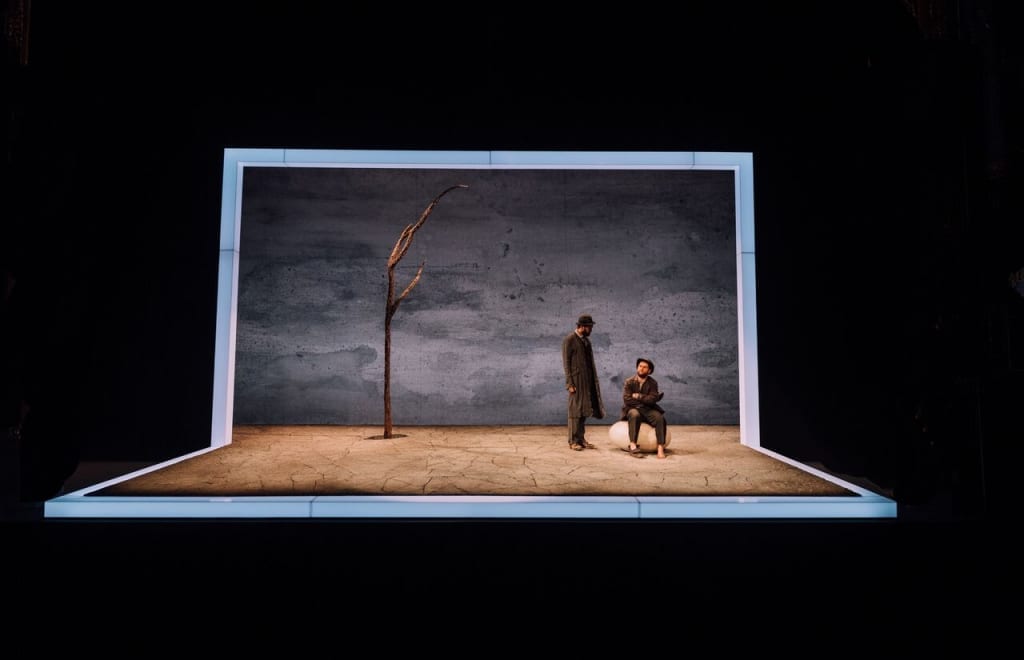

Waiting for Godot is set anywhere, nowhere and everywhere, is about anything, nothing and everything. It might be a parable for life (Vladimir: ‘all mankind is us’), or purgatory – endlessly waiting for Godot – or both, or neither. Vladimir and Estragon exist in a ‘compartment’ in a void (suggested by a glowing box surrounding the stage), doomed to endlessly repeat their days passing the time in meaningless activity. If it is a parable for life, it’s a pretty bleak one.

However, at least they always have each other, and no matter how often one of them threatens to storm off, they never do. The play ends with Vladimir and Estragon together on stage, still waiting. So maybe there’s hope after all.