Toronto is a city shaped and enriched by interactions between multiple diasporic cultures, home to countless stories of young people negotiating the tensions between assimilating into the urban life all around them and pressures (both from their family and internalized in themselves) to remain “loyal” or “pure” to their mother culture. The writers, director, and actors of Yellow Rabbit face this challenge head-on, and use it to produce a dramatic performance that grabs one’s attention from its opening moments and holds it for over an hour of a poignant, enlightening, and sometimes funny exploration of what it feels like to grow up self-identifying as Chinese in a city with a well-established Chinese community. The co-authors of the play, Bessie Cheng, Aaron Jan, and Gloria Mok, are the founding members of The Silk Bath collective, named after their prior trilingual play Silk Bath, which was a hit at the Toronto Fringe Festival in 2016.

The title of Yellow Rabbit appears to refer to the epithet “yellow race,” and to an old Chinese slang term of calling gay men “rabbits.” These two issues—racial purity and sexuality—are at the core of this work and its two major characters. The play is set in a dystopic near-future, when the world is a wasteland of few resources and constant race wars, where the only sanctuary for people of Chinese descent is to be recruited into Rich Man Hill (a thinly veiled reference to Toronto’s wealthy and largely Chinese suburban enclave Richmond Hill), where they are set to the task of propagating the Chinese race and preserving its culture under the watchful eye of a maternal dictator.

The main characters are played with energy and conviction by April Leung, labeled from the outset as Nü 女 (Chinese for “woman”), and En Lai Mah, called Nan 男 (“man”). These two must survive a series of ordeals overseen by “Mother” to prove the strength of their devotion to Chinese values, and their ability to produce Chinese offspring. (This would be challenging for this particular woman and man, as soon becomes clear.) Amanda Zhou plays “Mother” with the fervour of a charismatic dictator bent on realizing her ideology, while Bessie Cheng easily carries the most complex role of the play, as a young soldier devoted to the cause of defending her race, but unsure that total separation from others is the best way to achieve it. (Her character also develops nascent feelings for Nü, which would be unacceptable under the terms of Mother’s ideology.)

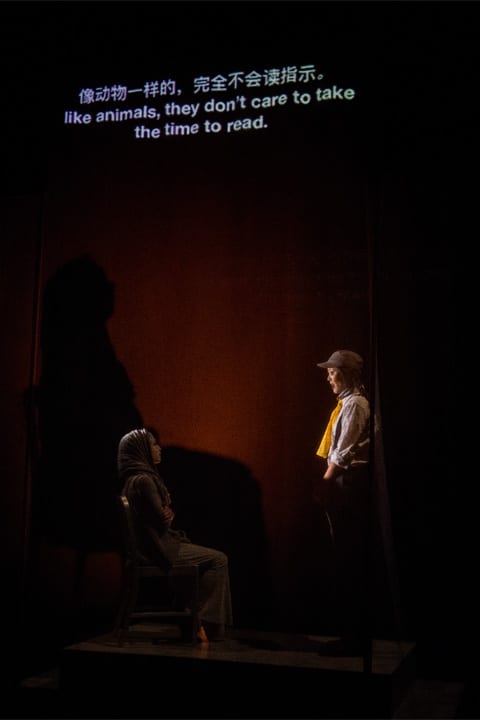

The entire action of the play takes place in the Rich Man Hill recruitment centre, which is defined solely by the use of curtains and screens, simple but effective lighting, and a lush soundscape that deftly complements the emotional tenor of the performances. The screens also serve as a surface on which to project occasional surtitles, as the script includes dialogue in English, Mandarin, and Cantonese. (The displacement of Cantonese by Mandarin as the most widely spoken dialect in Toronto’s Chinese community is referenced early in the play.) While the dialogue is at times somewhat “on the nose,” what it lacks in subtlety, it makes up with passion and sincerity. The director, Jasmine Chen, makes skilful use of multiple elements—blocking on the stage, projected images, and sound—to frame strong performances by all four actors, who quickly evoke the a whole range of conflicting emotions that burst forth when dealing with issues as charged as race and sexuality.

By the end of this riveting production, one has confidence that the emerging artists of the Chinese diaspora in Canada have found a clear and compelling voice in the Silk Bath Collective.