This new opera emerges as one product of collaboration between the Royal Opera House and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, who have sponsored composer Philip Venables in a doctoral residency. It takes as its text the last play of Sarah Kane, which ever since its posthumous premiere has been associated biographically with her own suicide. The title itself indeed refers to the time of day when the link between desperation and suicide is most likely. However, its treatment of depression, self-hatred, suicidal impulses and medical responses to them is much more open ended and impersonal than this suggests; and the musical setting, with plentiful polyphony and much hieratic chanting and invasive percussion only serves to underline its essential abstract austerity.

Just as in the original, there is no obvious narrative and no single lead character, though a doctor-patient dialogue is plausibly assembled between Lucy Schaufer and Gweneth-Ann Rand which provides a central spine of confrontation and misunderstanding, around which are located episodes of grief, exasperation at the world’s incomprehension, remembered happiness, and verbal self-evisceration. Violence is implied without direct representation, and the work is the more haunting and painful for leaving much for the interstitial imagination to process. The six singers, three sopranos and three mezzos, provide different commentaries and insights which the audience can then assemble into a complete picture. The orchestra partly underscores the voices, and then comes into its own in sparkling up-tempo toccata interludes, and prominent solo roles for antiphonal percussion, these last particularly effective in the scenes of confrontation.

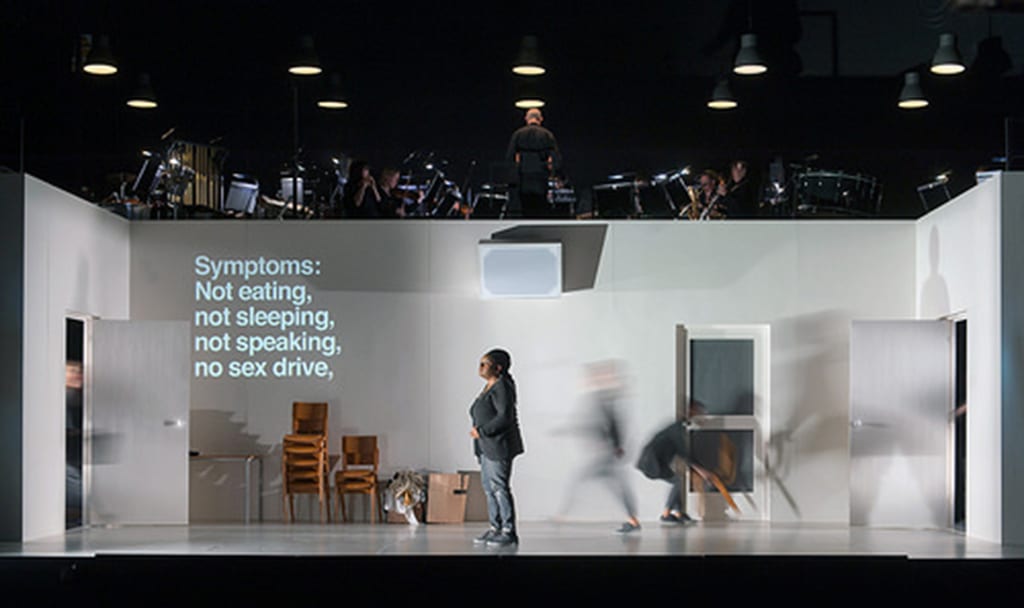

The stark white box of the set is a sharp contrast with the elaborate whipped-cream plasterwork excess of the Lyric Hammersmith itself, and the limitation of palette is enhanced by the sharply contrasted lighting effects and the stately choreography of D.M.Wood and Sarah Fahie, and the grey grunge of the costumes. The orchestra of twelve players perform above the set, rather than in a pit, and this produces a finely balanced sound, which offers potential lessons for other chamber ensembles. There were stylistic echoes of Stravinsky and Glass in the instrumental writing, and Monteverdi, Britten and Purcell in the vocal lines; but these were synthesised into an effective and individual style that suggests Venables is a composer to watch out for. Richard Baker conducted the intricate score impeccably, giving the singers plenty of space when they needed it, and letting his instrumentalists off the leash when the occasion demanded.

Among the singers Rand and Schaufer stood out, both for the richness of their distinctive tones, but also the emotional range they discovered in the very taxing vocal lines. For all the performers this must be a draining opera to perform, quite apart from its technical challenges. In line with T.S. Eliot’s dictum, ‘Humankind cannot bear very much reality’, this is not a work that one would want to perform, or indeed to hear, very often; yet everyone was fully committed to its execution.

Kane’s confronting theatre works are steeped in musical imagery, and in their extremes of situation and character present themselves as clear candidates for operatic treatment. Venables succeeds in adding real value to a play that has not yet been appreciated fully in its original form. This is a dark inward journey, akin in many ways to Hans Zender’s enhancement of Schubert’s Winterreise, recently performed at the Barbican. From these stark, underdetermined bones more can be created, just as players of different combinations can make something new each time out of Bach’s Art of Fugue. The formal minimalism of the text allows composer and performers to shape and interpret extreme emotions and infuse the abstract scenario with dramatic personality and individual fervour. The audience can then decide for itself where the balance lies between metaphor and reality.