Set on a basketball court in 1950s Alabama, SEPARATE AND EQUAL sets six young men against each other – three black, three white – navigating the prejudices within themselves and the societal forces that perpetuate bigotry and hatred. Inspired by testimonials from the Oral History Project at the Birmingham Civil Rights Museum, this performance, encompassing dance, drama, and sport, is produced by the University of Alabama in partnership with the Birmingham Civil Rights Museum and Birmingham Metro NAACP.

Two TV screens at either end of the court showing segregated water fountains switches over to a photo montage showing a century of racism and slavery leading up to the play’s hot day in Jefferson County: sharecroppers, Civil War, lynchings, Jim Crow.

Calvin Richardson (Adrian Baiddo) is a young African-American man attending college, to the disdain of his friends. “Education’s a white boy thing – they keep what’s theirs.” But they band together against Two Snakes (Will Badgett) when he starts heaping on Calvin, as well. At a time when Historic Black Colleges offer a way up, to get an education is means you’re an Uncle Tom.

Time on the court for blacks is designated for after church on Sundays, and yet here they are, the love of the game a forbidden lure. When they are met by three white boys they know, who at first attempt to own them, then challenge them, then join them in play, they are all joined in lawlessness: Ordinance 597 decrees whites and blacks must never share the court. It’s a clever tension – the act of play, benign in and of itself, spells trouble.

The boys know each other, but not as individuals, only as a color. As the narrative unfolds, each will get to tell his story, humanizing moments that pierce through the racism. But racism permeates every aspect of their lives.

Calvin’s mother is a housekeeper at the Roberts house, where Mrs. Roberts treats her well to her face, offering her a new dress, but cautions her son Edgar that he and Calvin can longer be friends. Her generation perpetuates the idea that blacks don’t want equality but what belongs rightly to the white race. It’s ingrained in her, and Edgar knows it so well, he recites the Klansman’s credo, that could stand in for the South’s defense of slavery during the Civil War: “To defend what’s ours, to take back what’s been stolen from us by thugs, by The Government, by Outsiders who don’t know a damn thing about us.”

Playwright Seth Panitch has a master’s command of the form. During flashbacks to the past, including a harrowing short scene of a black Korean War veteran returning home, only to be lynched for deigning to wear an officer’s uniform – the boys kneel as the action swirls around them. During another flashback, two sets of mothers and sons, their fathers respectively gone, circle and switch as they talk to the other’s son as their own. The conversations overlap, the mothers and the sons each having the same interchangeable conversations about loss, grief, and race. It’s a breathtaking moment that shows Panitch’s craft.

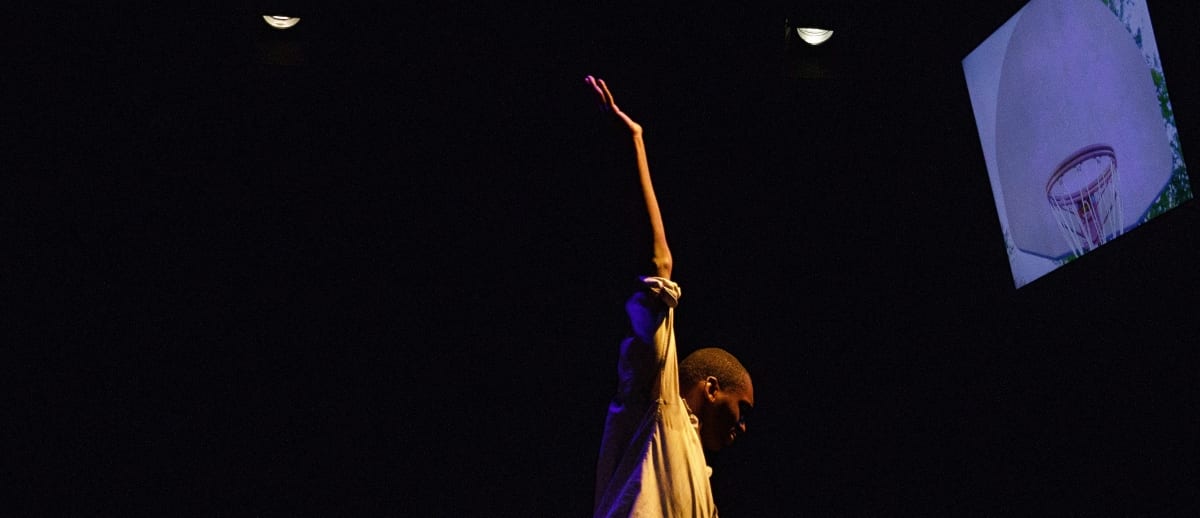

Lawrence Jackson’s choreography is skillful. It’s hard to believe the shenanigans on the court are practiced and not improvised. During one game scene, all six are backing up the court, paired black and white, impossible to tell if they’re dancing or playing.

Players Will Badgett and Ted Barton are especially notable here, playing multiple roles with skill and professionalism. While they have the smallest parts, they make them meaty and unforgettable, solid standouts who bring equal parts sorrow and terror to the drama. And their roles tip to the present. Even now, there is brutality, death, and despair inflicted on the African-American community by the police – found in the wrong place, wrongfully accused, playing basketball while black.

There’s a brilliant moment when the six players have finally shed their anger and are all in, playing for the sheer love of the game. The music that has accompanied previous court orchestrations – 1950s rockabilly – is instead a modern rock song, a musical hint that you are watching the future, an integrated game where the physical gifts of the players determines their superiority, not their skin color.