A body has been found in the desert outside Taos, New Mexico. It is identified, cremated and the ashes scattered. But is the person who inhabited it really dead?

Sam, played by Gemma Lawrence, has flown in from London to identify the body of her mother, Kath, from whom she has been estranged for three years. The major complication comes when Kath’s will is explained: Sam gets nothing, it all goes to the sinister Future Life Corporation. When Sam goes to investigate she finds the ultimate in glossy American lifestyle salesmanship offering ‘to take humanity into the third millennium.’ Future Life offers nothing less than an end to death. Her mother Kath is only literally dead, she is virtually alive.

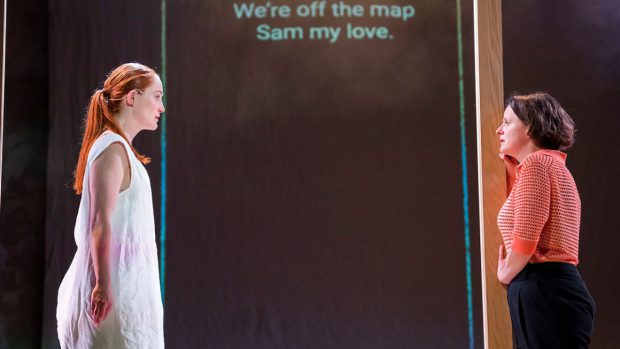

Sam is introduced to the ethereal figure of Kath in a white gown, speaking mechanically but with wit and awareness. She is a cyborg, a product of 3D modelling and years of Kath recording facts about herself at the Future Life labs. As Sam is told, ‘your mother had therapy all her life, many kinds, so she was highly skilled at emotional and biographical recall.’ It’s good to know there is a use for all that therapy after all.

David Farr’s new play is a brave experimental piece of sci-fi in theatre, one not usually attempted. However, the play begins to feel disjointed at the point when Sam tries to come to terms with the enormity of having a dead, but living mother with whom she still has emotional issues, and we cut to a series of sketches of Kath’s journey of self-development as we watch her past life revealed – her involvement in student protest, free love, encounter groups, the punk scene, and the advertising industry. At this stage the plot of the daughter’s emotional wrangles is overtaken by that of the mother running through her past life, though the sparing use of 1960s and ‘70s music evokes the time perfectly.

Eve Ponsonby gives a stand out-performance as Kath who is needy, belligerent and sometimes screaming as a live woman, but icily sardonic as a cyborg. This is the story of someone who has always been self-willed. As an artist she needs to follow her own vision, but sometimes she is merely selfish – as in her infidelity because ‘the opportunity was gaping’, and in her refusal to do the work she is being paid for because she doesn’t feel like it. Facing the end of her life, she doesn’t want to die, why should she if she can afford not to?

The play points to one of the paradoxes of Artificial Intelligence: however detailed an AI programme is, an essential element is missing. Cyborg Kath has all the facts of living Kath’s life but no convincing humanity. In order to grow emotionally in her artificial death state and become a realistic person she needs human interaction. If her daughter chooses to keep her mother ‘alive’, and not press the delete button, she would have to feed Kath’s emotional needs, presumably for the rest of her life. Kath, having been a user in life, does not let a little thing like death get in the way of her being a bad mother.

The concepts are superb but there are problems with the execution. For example, what could be an interesting exploration of character with Kath’s yearning to be back with her college boyfriend is thrown away in a plot device where she makes a cyborg of him. A rather unconvincing sub-plot features the excellent Jason Ives-Moiba as Sam’s lawyer who has suffered a conventional bereavement and who feel his dead wife comes to him.

There are some brilliant ideas here, and powerful themes: bereavement, AI, student protest, vacuous advertising, corporate encroachment and mother- daughter conflict, but in the end the play never fully hangs together. It never really comes to life, it is always less than the sum of its parts

Performance Dates: 26 Oct-12 November 2022