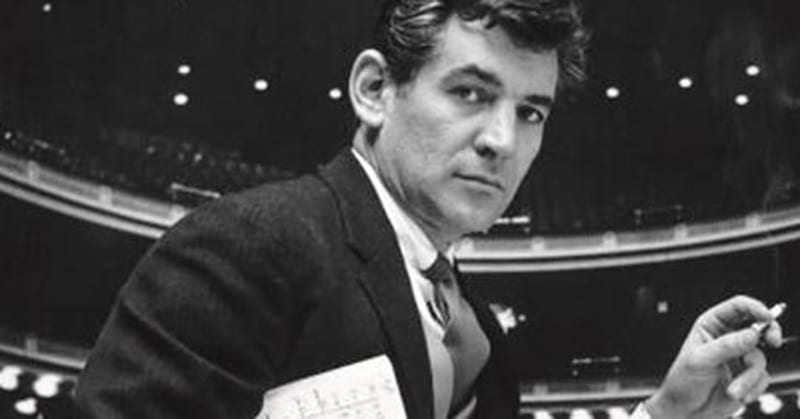

Allen Shawn’s new book about Leonard Bernstein probably doesn’t replace the magisterial Humphrey Burton tome about the polymath’s extraordinary life, but it certainly is a superb pendant to it, is very accessible and is also a very fine shorter introduction to the extraordinary and very important life of a great man. Its emphasis on considering each of Bernstein’s compositions in turn as well as his TV programmes, lectures and didactic concerts for children, is especially interesting. I’ve always preferred Bernstein to, say, his rival and near-contemporary Herbert von Karajan, whose international post-World War II career so definitively overlapped with Bernstein’s; and I would bet a fair amount that it is Bernstein’s reputation as a conductor and composer that will grow over the next decades while von Karajan will be found to be, in some ways, a more limited artist. I also expect people to become more aware of Bernstein’s persona, his reputation as a mensch, a real human being. He was flawed; he was complex; he was madly in love with his wife for a time and with her formed one of the early power couples but he was also essentially gay and ultimately tormented by his love for men. He could be selfish and thoughtless and he caused problems or one sort or another for many people who knew him or who knew him or got close to him, as this book suggests; but he also was a generous teacher, a superlative mentor for other composers and conductors; and a brilliant entertainer as a conductor, as a teacher and as a composer. He was also a very, very good friend to have. And he smoked a drank way too much! How can you not want to know the story of the man who wrote On the Town, Wonderful Town, West Side Story and Candide as well as one of the worst atonal operas in existence? He was a man who had a huge influence on teaching about music to at least two generations of children in North America. Two things come through strongly in this book: his ability to form lasting, loving, loyal relationships both personally and professionally; and his complete dedication to conducting, teaching and composing. He was also a brilliant pianist and a great performer whether on the podium, the piano bench or in front of a crowd and/or cameras delivering lectures. Add to all his other gifts that he was a fine writer. Indeed, Shawn shows clearly that he was, in everything he did, above all, a generous and enthusiastic communicator. There was much about his life that, in retrospect, seems messy and sad, but what seems to stand out from this story is how much he was loved and how much joy he brought to everything he did professionally as well as personally. As well as telling the story of the life and placing it carefully in the social and political context of the times, the book carefully analyses and assesses each of his works individually, cumulatively building up a picture of how important the man was to twentieth century culture both in America and throughout the world; and Shawn’s dealing so fully with this major aspect of Bernstein’s life and mentality, with his artistic intensity and the development of his creativity, made me want to go back to listen to things like his symphonies or even his opera A Quiet Place in the light of what was said here. Because Bernstein was so gifted and energetic in so many different areas, some people considered him to be facile. Shawn clearly admires the results and argues against that belief. I myself had a brief but delightful acquaintance with Bernstein towards the end of his life that was enriching and enjoyable out of all proportion to the time I spent with him. He even had a joke for me that was delivered a year after his death by his assistant conductor, Michael Barrett. I came away from reading this book remembering the power and charm of his personality, his astonishing polymorphic brilliance, and that, above all, he was a genuinely generous and endlessly creative man.