Sound designers are in the game of manipulation. They exploit our emotional instincts to intensify and control the dramatic experience. With the slow timbre of a bass drum, the creak of a door, or the slice of a knife into flesh, they widen eyes, shorten breath and send hearts racing. Berberian Sound Studio at the Donmar Warehouse explores just how far sound can go in shaping the audience experience, not only intellectually, but physically.

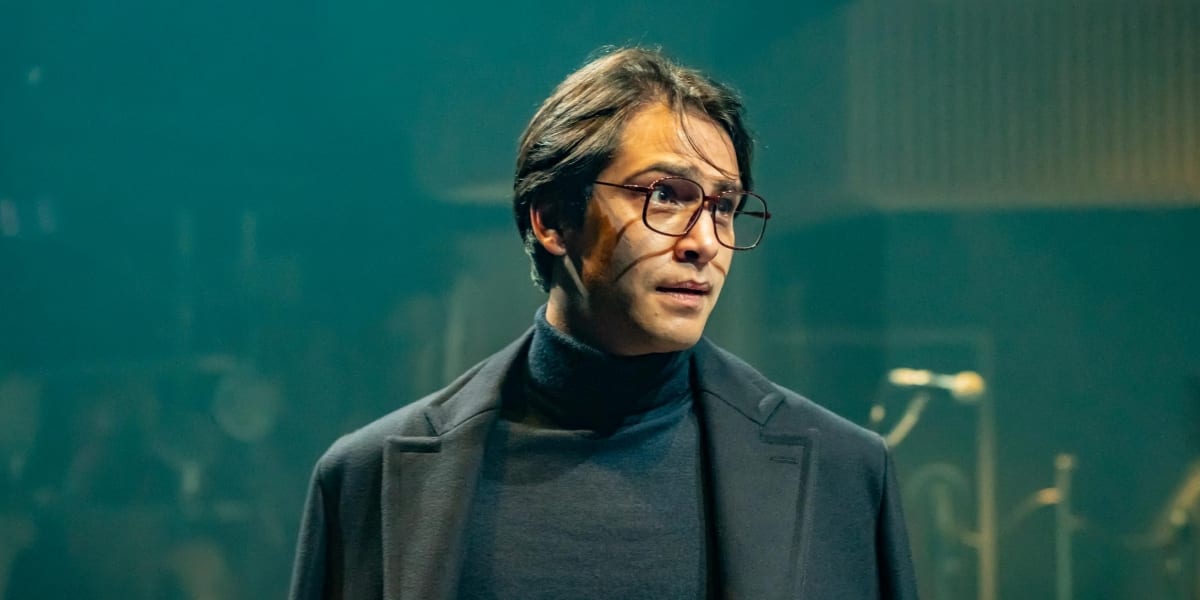

Based on Peter Strickland’s 2012 film of the same name, the action follows Gilderoy, a tightly-wound British Foley artist specialising in dry nature documentaries, who is summoned to Italy to work on a “Giallo” horror film – known for their provocative blend of sex and violence. Tom Brookes is excellent, bringing a shy charm to this oddball character, who seems most comfortable working alone in his mother’s shed.

Director Tom Scutt made his name in another pillar of the theatre world – set design. As one would hope, his debut turn as a director makes creative and intelligent use of a beautiful space. A glass-fronted mixing studio filled with eclectic posters and objects is wedged upstage alongside the actor’s recording booth. They stand behind the Foley-stage, which is decked out with vegetables, chains, water buckets and various props available to the sound technicians. Two eccentric Italian assistants smash their way between them while staring up at a projection of the film that extends over the heads of the audience. They time their movements to correspond with the gory action, dramatically plunging knives into melons and snipping carrots with scissors. We are the audience of an audience, intuiting the film through the sounds, gestures and expressions of the actors on stage – an intriguing collision of slapstick comedy and gory horror.

The play is drenched in filmic references. There is an interesting parallel between Gilderoy and the protagonist of Hitchcock’s horror classic Psycho, who infamously claims ‘a boy’s best friend is his mother’. Gilderoy’s own Freudian tendencies become increasingly explicit over the course of the play. He receives tape-recorded voice messages from his mother, listening to them with ritual intensity before cutting and manipulating her voice with a sound mixer to produce peculiar acoustic effects.

His behaviour becomes increasingly volatile as he immerses himself in the fetishized violence of Giallo, whose gruesome sounds he labours to create. This culminates in a disturbing torture episode, during which he afflicts an unwitting voice actress with excruciating sonic frequencies to elicit the perfect blood-curdling scream. She erupts from the booth, violently berating him while hurling wads of remnant cabbage, but Gilderoy simply stares through the glass with blank, sociopathic interest.

This moment of misogynist abuse is the logical product of the fetishization of female suffering that characterises the Giallo genre and which pervades the studio environment. Earlier on, the filmmaker, a self-obsessed wannabe auteur, dismisses a concern with the film’s content from one of the actresses, making vague references to artistic licence, while the studio manager incessantly preys upon and demeans the female cast in front of Gilderoy.

The fractured episodic structure that comprises the latter sections of the play, bound together with a brutally intense soundtrack, seems to evoke the chaotic, primal masculinity that undermines the ethical interests of the female characters. Writer Joel Horwood does well to translate the cinematic intensity of the film to the stage, but this ending feels like an easy way to call time on a difficult set of intersecting issues – misogyny, mental health, cultural responsibility. Despite its length at one hour and 40 minutes, no interval, Berberian Sound Studio would benefit from a second act that allows these narratives to play out more organically.