Sharp rappings on the door and a woman shouting sets us up for an intense evening of desperation, isolation and fragility. But do not despair as it is also about two people finding each other in a wilderness of life.

Rosanne bursts on to the scene in her bridal gown and wedding veil speaking in a stream of consciousness, grabbing the air in an anxiety overflow. She wakes the slumbering Henry who stands silently wrapped in blankets while he listens to her hysterical outflow of words. This is the pitch kept up all evening.

We are presented with a stark set of black walls, a bed, cooker and a table. The scene reflects the bleakness of Henry’s life in the wilderness of both Alaska and inside his own head. He is a loner, living in a shack on his time off from working on oil rigs in the middle of nowhere. His physical isolation is a choice he has made after a tragedy in his own life. She has escaped a doomed wedding. They are both trapped in his cabin as a wild blizzard rages outside, her car having stalled in the snow. She cannot leave – as Henry tells us often, it is just white out there, the sky meets the floor and no-one knows what is real, or the right way up, a figuration of life itself.

Michael Feldsher as Henry Harry and Sam Kamras as Rosanne give their all in this powerful drama. In forceful performances, they portray people lost in life. The names of the characters are incidental as they are universal, we can recognise their difficulties. We learn she has driven two thousand miles from Arizona to Alaska as though she were floating above the car, like a soul outside of its body.

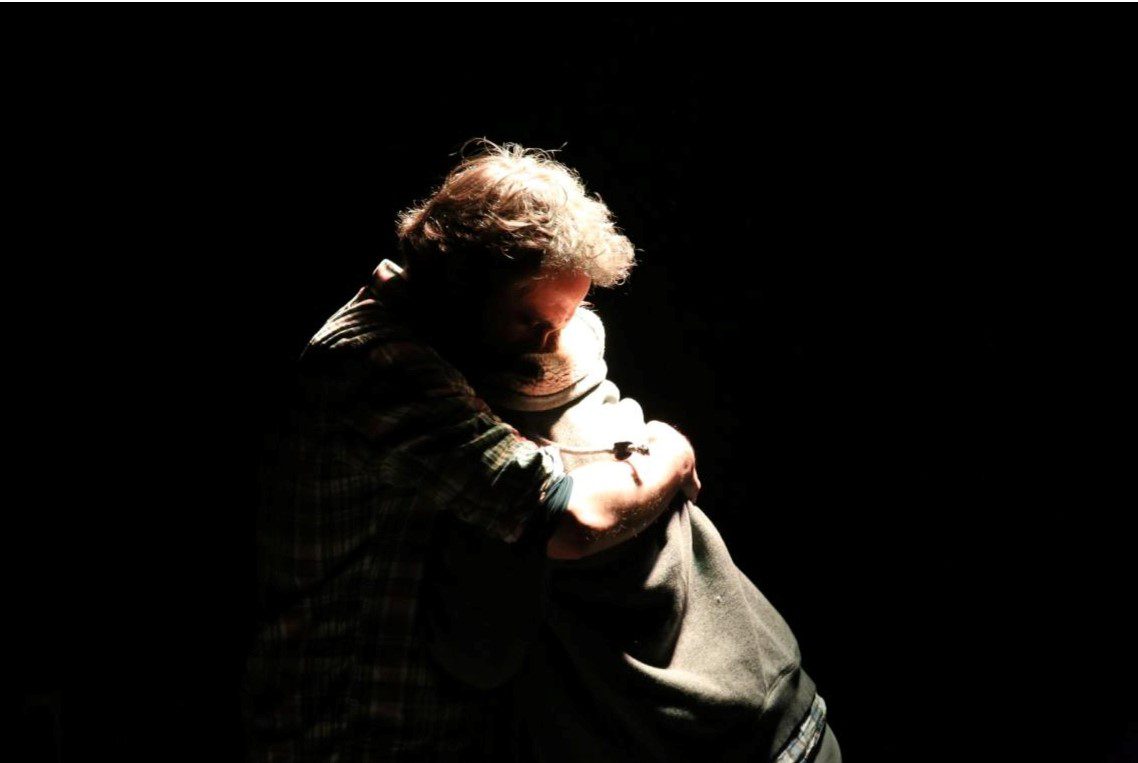

The strength of acting of both parts is stunning. The two of them hold the stage completely with very little support except the projection of the tightly-scripted words and the force of their acting. Their verbal toing and froing is like a battle, struggling to come to terms with both their own wounds and each other in a fragile space of the unknown – he tenderly undresses her, puts her to bed, and feeds her soup, but does not want to be known as a person who cares about people; she is volatile, but she feels she is weak. They know neither themselves nor each other and the reveals show us their sad histories, and the shaky connection they are making, reaching out across a void of unknowingness and uncertainty. The volley of exchanges are attempts to understand themselves, make sense of life, and to find each other. Through their intimate exploration of the past, they realise there may be a future after all.

At the centre of all the drama is a pair of Rosanne’s bridal satin slippers which Harry placed out of sight in an oven, then cooked them – he could not bear to see them or contemplate what they meant. They talk about the scars of life which leave the brilliant traces of the play’s title.

The play was influenced by a poem by the playwright’s mother, Avah Pevlor Johnson called ‘Individuation’; the poem speaks of being pelted with particles from the dark side and flung into a black hole which reflects the tone of the play. Cindy Lou Johnson first wrote the play in 1989 but it holds true today and is perhaps more relevant in a time when we are suffering from the isolation of covid and the bleakness of war.