Coriolanus comes to the Barbican as the first instalment of the RSC’s Roman season in a transfer from Stratford. Any production of this under-performed play from the peak of the playwright’s career is welcome, but this one is a very indifferent vehicle for conveying the greatness of this study in ornery character and wily, intricate, switch-back politics. While there are several fine supporting performances and an intriguingly flexible set, the poor and cavalier handling of the text makes the first half a real grind and ordeal to sit through. In the second half where there is more action, and rather less politics and poetry, the scenes flow more freely, redeeming some of the torpor of the earlier scenes.

This is more a mythological than historical play with the focus on political archetypes that easily transcend the Roman era: the focused, austere proud patrician soldier, as ill-adapted to politics as he is ferociously successful on the battlefield; the mother who has made her son so through trying to live her life through his; the smooth equivocating and calculating tribunes seeking to exploit tensions between people and senators to their own advantage; the senators aiming to protect their own privileged position; the people, easily led, and hovering between hero worship and mob rule; and the rivals to Rome, hoping to exploit Rome’s internal divisions to their own advantage.

Some of these roles are excellently inhabited. Paul Jesson’s polished, emollient Mennenius is the epitome of an establishment figure engaged in self-preservation, shaping the text meaningfully to his advantage. The same may be said for Haydn Gwynne’s Volumnia, though she is best at projecting the fierceness of her character (‘Anger is my meat’), which leaves her great speech of supplication to her son, somehow lacking in emotional light and shade. James Corrigan is excellent in the somewhat ungrateful role of Tullus Aufidius, easily inhabiting the physical demands and finding more of a homoerotic bromance with Coriolanus than is usual. This helps to make a lot more sense of his final act of violence. As the two ambitious tribunes, Martina Laird and Jackie Morrison are all too convincing as politicians for whom every event offers possibilities that could be turned to their advantage. This was one of the occasions when gender-blind casting really worked to advantage in focusing attention on the processes of Machiavellian chicanery involved, irrespective of gender.

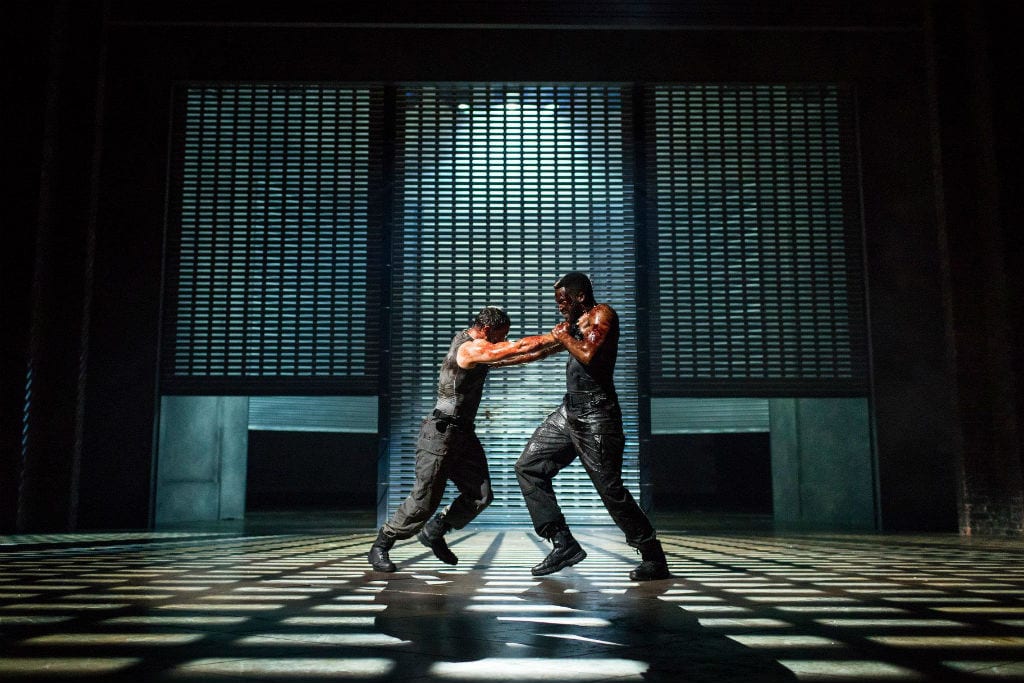

This play stands or falls on its central character who bestrides each act. While it is not necessarily a middle-aged role, it does need to be played with a settled maturity and persona that was not present in Sope Dirisu’s performance, at least not until the final stages. The martial side of the role was easily his grasp, but he failed to use the knotty but refulgent poetry of his lines to good advantage to suggest the man within. In the crucial market-place scene he did not really evince his disdain for the people or the tensions within himself between hauteur and self-contempt. His performance was at its best in his scenes with Corrigan, especially at the Volscian Banquet, with its exquisite trade-offs between low comedy and grand rhetoric. The climactic scene with his mother which should bring all the strands of the play together in one confrontation also seemed underpowered and lacking in really detailed direction.

Designer Robert Innes Hopkins does a fine job with a series of metal shutters in varying our sense of location from interior to exterior, from battlefield or market-place to Deco drawing room. Modern-dress costume suits this play well, and still allows social distinctions to be drawn between plebs and patricians. There was an extensive musical soundtrack provided for a singer and small ensemble by composer Mira Calix. This was sweet on the ear but rarely enhanced or added to the meaning of the action in significant ways.

Ultimately this production does not deserve either a decisive thumbs up or thumbs down, but there is still a sense of missed opportunities.