Creditors is an exploration of sex and sexuality, of power and weakness in men and women, of how partners can be consumed by each other. When callow Adolph (Edward Franklin) meets older, experienced Gustave (Stuart McQuarrie), he unwisely opens up to him about his absent wife Tekla (Adura Onashile). Gustave’s smooth and pleasant exterior starts to morph into something altogether more unpleasant, with dramatic consequences.

As written, Creditors is a taut and claustrophobic three-hander, full of psychological torture and manipulation. For the first two scenes, this production does a decent job of maintaining this. First Adolph and Gustave and then Adolph and Tekla are alone on stage, complemented by a sculpted figure silently standing in for the absent party. It is a shame that in the third scene all three characters are on stage at once, rather diminishing the ominous effect created by the watching sculpture.

Unfortunately, this is not the only misstep, and the innate quality of the play cannot rescue it from some peculiar production choices. Part of the strength of Creditors should be its naturalistic feel, a sense that what is happening on stage could happen in any living room across the country. The insertion of a troupe of girl guides occasionally striding across the stage to no obvious purpose is, therefore, something of a distraction; they feel like they belong in a different play.

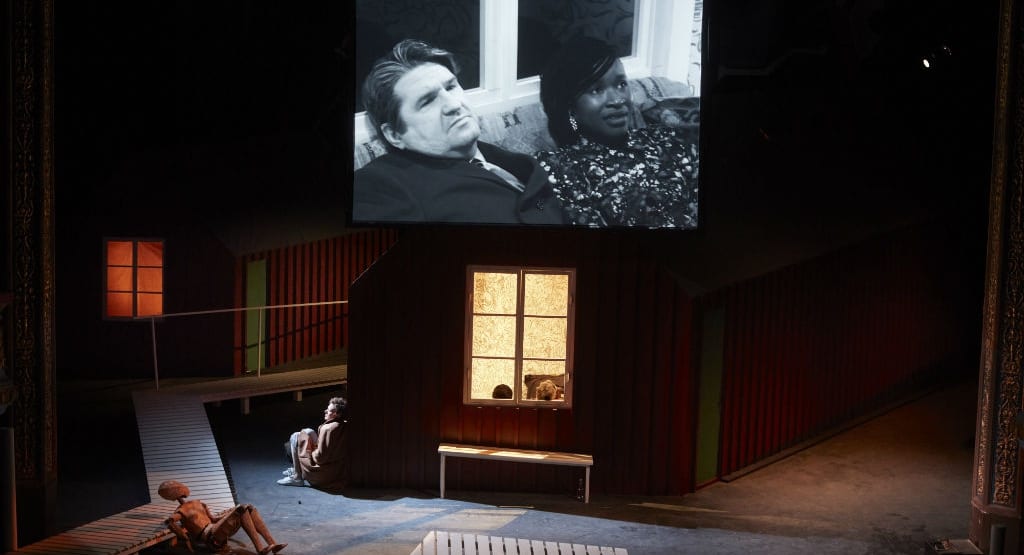

The choice of staging, too, weakens the play. By setting most of the action on the shore of a lake (instead of inside a single room, as intended), much of the claustrophobia of the original work is lost. This is exacerbated in the final scene, which takes place inside one of the lakeside cabins, with no way for the audience to see in. Instead, a screen drops from the roof, and the action inside the cabin is relayed to us via a live camera stream.

This has several negative consequences. It entirely divorces the audience from the actors, removing any sense of intimacy. Frequent views of the camera person filming the actors wreck the sensation of the play being a tight three-hander. By introducing unnecessary technology, the play becomes hostage to the vagaries of disruptions such as crackling microphones. It has none of the benefits of either film or theatre while incorporating negative elements from both. Rather than being an innovative staging choice, this feels more like a failure of imagination.

Despite this, the cast’s performances are largely quite good. Franklin as Adolph is suitably childish and weak-jawed in his pandering to McQuarrie’s manipulative Gustave. McQuarrie himself is sly and manipulative as Gustave while Onashile’s Tekla is a sparkling addition to the stage when she appears, sultry and sulky by turns. Unfortunately, by having to act at one remove in the key final scene, both performances lose their bite.

Overall, this production of Creditors is something of a disappointment. There is a sense of the taught, manipulative tragedy it could have been, but it never really delivers. The bold staging choices do not come off, and in fact seem to fly in the face of the way the play is intended to work. Creditors is clearly a fine play, but this version of it does not do it justice.