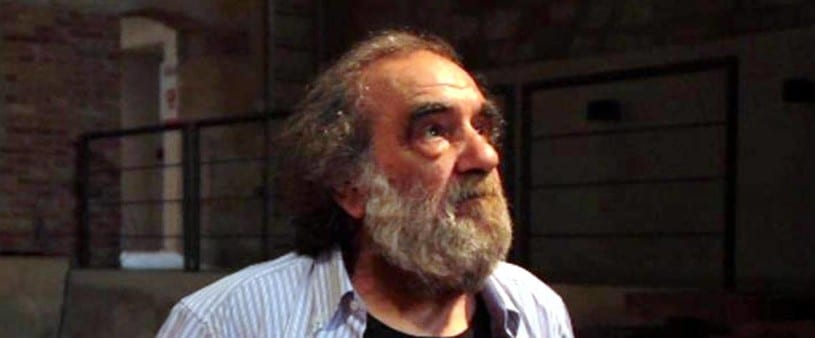

Franco Scaldati in conversation with Rivka Jacobson in 2012

He is tall and rather scruffy looking. His untamed beard and moustache dominate his face, that is, until you get nearer to him and look into his eyes. Then, you are transfixed by what he has to say. His eyes and body language make the translation from Italian into English a great deal easier. His interpreter tells me Scaldati is the National Poet of Sicily, a playwright and ‘Capocomico’ (artistic director) in Sicily. Italian theatre critics I met in Palermo, referred to him as Sicily’s Samuel Beckett

After a performance of his play Piccole lune per due Clown (Small Moons for Two Clowns), at Teatro Bellini, in Palermo, Sicily, we sat together at the nearest café.

In an odd way he seems the embodiment of the old archetypal poet, scruffy with a greyish beard and moustache, his shirt partly un-tucked, but warm, thoughtful, very insightful with a touch of melancholy in his eyes.

His place of birth, he replies is Montelepre (Sicilian: Muncilebbri), a town and commune in the province of Palermo, which is renowned for the birth place of the Sicilian bandit Salvatore Giuliano.

He was born in April 1943, his father was a merchant and they owned a bar, but during World War II, his parents with their five young sons, had to flee Palermo.

Education & Theatre

Rivka: Which university did you go to?

Scaldati laughs. He looks at his friend and colleague Melino Imparato: I did not start High School let alone a university he says. Life was my school and university.

He continues to explain that he began work as a tailor from the age of twelve. It’s only when he married and had a child that he decided to dedicate his life to the theatre. Today, his two sons and grandchildren work and act with him.

Scaldati points out I was always interested in the performing arts, I used to act in the local theatre. I worked as a tailor by day and acted in the evenings.

At the age of 23, he and Melino Imparato joined forces and set up their own troupe. It was only when they needed someone to write a play for their group that Scaldati wrote his first play. This piece created the working-style that he continued to use for the remainder of his career. The group as a whole would collaborate on a piece, and then Scaldati would edit and refine the play.

Scaldati: I draw from the people for the people. I created a new language using popular language and slang but constructing it in a poetic way. I am inspired by William Shakespeare, William Blake and the Pre-Raphaelite painters. They help me create symbolic and romantic images which I adorn with popular scenes from life and a lifestyle that emerged after the World War II in Palermo which is now lost, he says.

In his plays he dwells on the past that no longer exists, but he manages to bring relevance to it in the present.

The playwright & director

Scaldati is well aware of the need to create escapism so he draws on situations that are comical and embellishes them with surrealism. His animals speak and characters can talk to the sun and moon. He wants the audience to have fun by creating a new universe in which they live and anything can happen within it. Something, I guess akin to children’s theatre, but for adults!

Scaldati is a realist with a romantic soul. He is aware of the sharp contradictions created by the illusion on stage and the reality people have to meet on a daily basis – after all this is the story of his life, until he became famous.

Scaldati: You have to have a light approach and empty your mind in order to enjoy yourself within this economic reality. It is important to create a reality that demands nothing back. This is life. Like the world of animals, we need to be completely and utterly free. We restrict this aspect of ourselves too much, but it lives in us. The real freedom is when you can communicate with everything. In theatre, everything is life and life is born from that exchange. The energy of people is unleashed between things, and yet actors must be extremely disciplined in order to be liberated. In the Asian theatre tradition discipline is essential to freedom.

R: You acted in the production of Piccole lune per due Clown. Do you enjoy acting in your own plays?

S: I always act in my own plays, even if it is a very small role: I like to share the experience of the performance with my actors. The actor creates a mask which allows him to liberate himself, using the invisible mask to get rid of rationality.

The dialogues in Piccole lune were in Sicilian dialect. My Italian interpreter was unable to assist. I asked him about the play. He explained that at the beginning there is a person who is dying, and she accepts her fate. While the other girls come to help her, there is personification of nature. At the end, a prostitute is the one who comes and gives her body to poetry. I am certain there was a great deal more as the local audience seemed moved and laughed a great deal.

R: To those, like me, not familiar with your work, can one say that Piccole lune per due Clown has the hallmark of your work?

S: Of course not. Some of my plays contain violence and are harsh: they enter the darker side of human nature. Piccolo lune is a softer and more tender side of my writing. Other plays discuss murder, incestuous relationships and some violent family relationships as well as violence within the world. I depict the world of the poor and the world of the vagabond. For fifteen years I worked in the roughest district of Palermo called Albergaria. My company and I worked in that area to absorb the atmosphere, the way of life and the language and the play that followed communicated all these elements.

He is fascinated by language therefore: he draws a great deal on the local dialect. Both the physical aspect, body language and the verbal aspect, spoken language, are central to every play. His characters are usually people who have been hurt or suffered. He is not interested in the purely physical story, but in the spirit of each character.

He holds the pre-Socratic philosophy and admires Samuel Beckett. He has adapted Hamlet, The Tempest and Macbeth into Sicilian.

He said that Shakespeare is an infinite universe, and beyond Shakespeare there is only God.

Some of Scaldati’s work has not been performed, though during my brief visit to Palermo, I met one individual, who has written a book on Scaldati’s work. Unfortunately for me, it is in Italian, a language I have not yet managed to master.

R: Do you believe in God?

S: We are not sure if there is God or not; but there is a presence of something.

I believe in God as an undefined being. A God that is severe but also forgiving, a God that doesn’t judge but is understanding.

Before concluding the meeting, I had to ask him how long he had had his beard.

Scaldati, with a friendly laugh says: For many years my wife has asked me to shave it off. But I cannot remember how my face looks like without it. It has to stay!