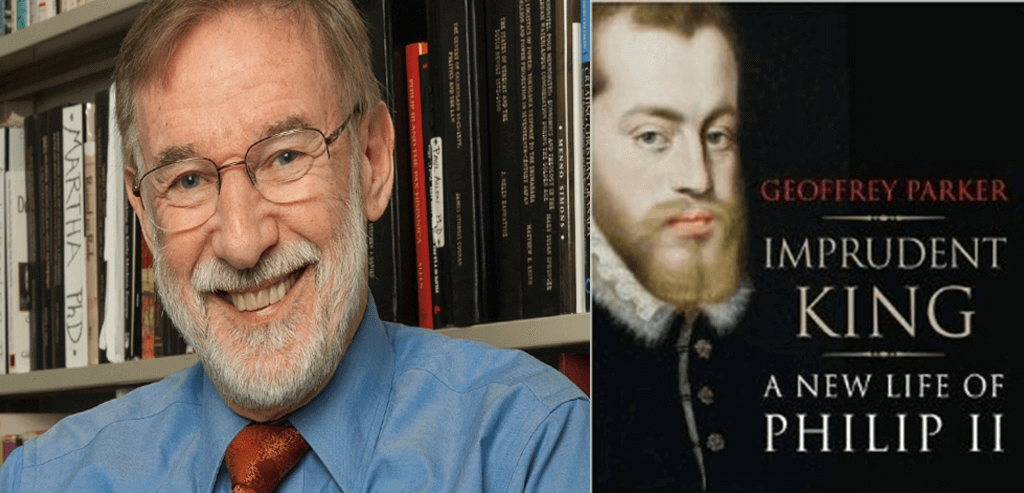

Anyone interested in Schiller’s play Don Carlos, or in the great Verdi opera based upon it, must be curious about the real historic background to these two major works of art. There is no shortage of decent biographies of Philip II and also no shortage of appearances of the character in the biographies of Mary I or Elizabeth I of England or several other contemporaries, but this new and extremely scholarly biography by Geoffrey Parker is now my “go to” book for anyone who wants to know about this troubling, difficult monarch.

Prize winning historian Parker has had access to a recent, astonishing archival discovery – 3000 documents in the vaults of the Hispanic Society of America in New York City that have mostly not been read since the time of Philip II himself. Many of the documents confirm what is already accepted interpretation of the personality of this king and also of his reign in general; but some suggest some significant changes to our understanding of this man. Dealing with his relationship to his father and his heritage and ending with this religious king’s supposed ascent into heaven in 1603, the book is very well written and presents a compelling story.

The Don Carlo story is, of course, only an episode in the tale of Philip II – his birth, his upbringing, his erratic behaviour, his arrest are all there – and is very different in reality from what Schiller (and thus Verdi) made of it. However, the book manages to examine and portray the personality of Philip, his likes, his dislikes and his psychological issues, cogently and convincingly; and as such is the perfect place to find out the truth behind his portrayal by Schiller and Verdi. Of course, neither of these great artists had access to a great deal of the material that Parker can deal with and they also were closer to the gossip and the distortions; and yet, perhaps the most exciting thing about this book for those coming to it from the play and opera is that, even if the historical details of the man’s life and his relationship with his son, are wildly romanticised, one comes away from reading this book convinced that both dramatists got the gist of the man. The authoritarian self-belief, the religious narrowness and bigotry, and the immense loneliness and pain that you find in Verdi’s music and Schiller’s dramatisation are all given greater credence by this book. He micromanaged, trusted no one, and wasted too much time on the trivia in periods of real crisis that needed understanding of the bigger issues. Also, of course, you come away understanding the real background to the Posa/King Philip friendship; and so much more – Charles V’s abdication, the marriage to Mary Tudor, the various wars including the troubles in the Netherlands, the wooing of Elizabeth I, the terrible religious conflicts of this era which is the protracted and very painful, bloody dawning of modernism; the Imperialism; the Armada. All of it seems to be impeccably researched and Parker’s conclusions and understanding are completely convincing. It is a rich and complex tale that is being told and does require attention to detail.

A friend of mine to whom I gave a copy of the book for his birthday because of his love of the Verdi opera complained to me that this was not an easy book to read. It is meticulous in detailing Philip’s religious attitudes, the background of the period, and the administrative details of this man’s obsessive control of his empire. It sets everything in scholarly context. But in the end my friend said it was worth the effort to get through it, even though he usually preferred Alison Weir or Philippa Gregory for learning about the history of this era. Personally, I felt the scholarship was immensely important in convincing me about the character of this somewhat dour but also sad, troubled monarch. There is material here for a Freudian study. If you want a quick fix on the background of Philip, there are no doubt easier and briefer ways to get it.

I would have liked to have more in the book about Philip’s zeal for collecting and commissioning art and his use of it for propaganda; and I would have liked to have even more information about the Inquisition. But if you want really to understand the man, his nurture, his nature and the background thinking and conflicts of his important era when the early foundations of the Enlightenment were beginning to be laid down, this is the place to go for what will probably be the definitive study of this monarch for some time to come. Philip was isolated, tormented and, at times, very imprudent as well as willfully narrow – and this book tells you all about that and more quite clearly and reliably. It also makes sense of the great sequence of Philip’s relationship with the Grand Inquisitor in both the play and the opera. I recommend it very highly for anyone willing to take the trouble. And then go back and see what Schiller and Verdi made of Philip and their insights into his soul through their art.