Mamzer Bastard, a ninety-minute opera by the 29-year-old Israeli composer, Na’ama Zisser, is an impressive achievement.

The title is a tautology once the term is placed in the Jewish religious context. It means a person born from a forbidden relationship, such as bigamy. That person is prohibited from marrying and is expelled from the congregation.

The libretto is written by two women, one of whom is the composer’s sister, Rachel Zisser, and the other Rachel’s partner, Samantha Newton.

Na’ama Zisser, herself of a Jewish orthodox background, explores through her composition issues such as isolation, anxiety, fear and the question of identity. Her composition is often visceral, yet unsentimental. Warmth, dreams and aspirations are interwoven via carefully selected cantorial (hazzanut) pieces.

The action takes place in New York City on 13 July 1977, the night of one of the biggest blackouts in the city’s history. The protagonist is twenty-one-year-old Yoel (Collin Shay), a man from an ultra-Orthodox Jewish family and community. He is to enter an arranged marriage the next day. Unsure that he is ready to wed, he decides to explore the milieu outside his closed community. He becomes lost in the darkened streets and is attacked by a mugger. A stranger, adequately performed by Steven Page, saves his life. The dialogue between the two reveals that the stranger knows a great deal about Yoel and his mother, Esther, who married in Europe and survived the holocaust. Esther, whom Gundula Hintz effectively brings to life, believes her long-lost husband perished in the concentration camps, hence her marriage to David (Robert Burt), Yoel’s father.

The libretto, written in a form of a screenplay, lends itself to dynamics that are not necessarily dramatically convincing. The show moves rapidly from one location to another with the narrative leaping forward and backwards in time.

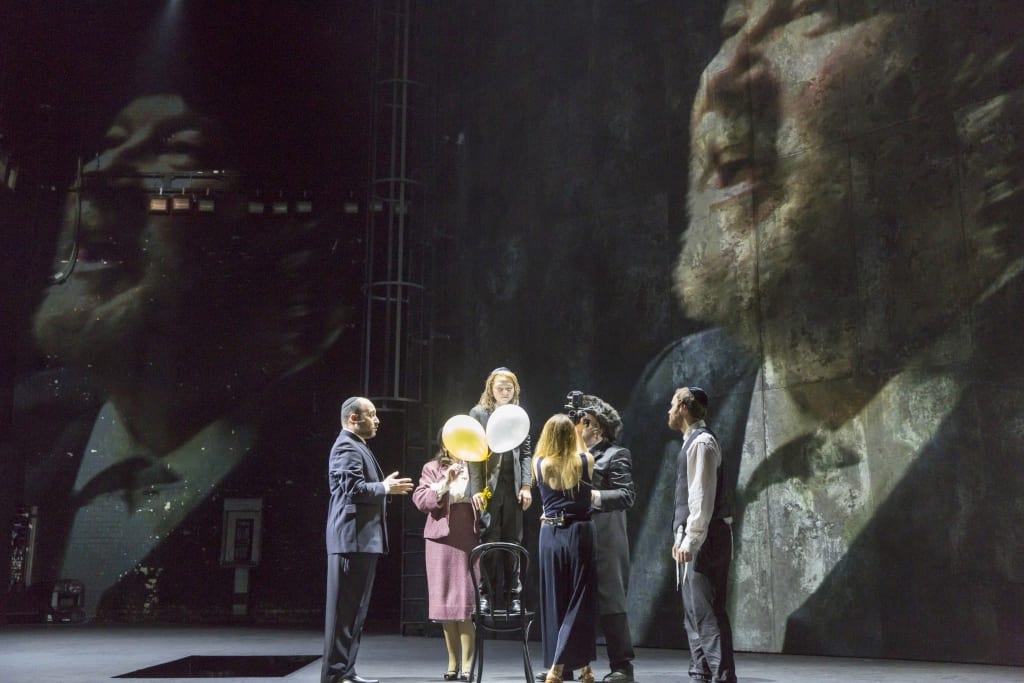

The music score is a mix of amplified chamber orchestra, cantorial pieces and cinematic sound, all designed to integrate and create an immersive feel. Unfortunately, the drama on stage, combined with the projected images and the presence of the cinematographer, comes across as noisy. The characters seem disjointed and communication between them is devoid of the emotional elements necessary to be convincing and draw the audience in. The action lacks impact and even dramatic music from the orchestra fails to dislodge the feeling of watching amateur theatre.

The highlights of the production are the cantorial pieces. It is the cantor from the Hampton Synagogue in New York, Netanel Hershtik, whose singing injects the performance with operatic qualities. Zisser’s choice of the cantorial pieces is superb and meaningful in the context of the libretto. From the first piece, known as ‘Song of Ascents,’ Psalm 126, and sung in the musical version of the celebrated Cantor Yossele Rosenblatt (1882-1933), to the last, the melancholy poem ‘I reduce myself / to a point ” by Avraham Halfi, the selections are moving and help cast some light onto the world Zisser sets out to explore.

Jay Scheib’s direction is brilliant in theory, but the execution is chaotic and disjointed. The dramatic tension is missing throughout. The excessive intrusion of the camera woman on stage following the unfolding story seems pretentious and hindered the intimate moments in the performance.

The production’s failings distracted from Zisser’s composition and the beauty of the incorporated cantorial modes in the opera.

*Na’ama Zisser is a doctoral composer-in-residence at London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama (GSMD); the opera serves as her thesis and is a co-commission between the Royal Opera and the GSMD in association with the Hackney Empire.