At the talk back session, prolific and charming playwright/director Israel Horowitz told us how the play had been inspired by a story of a man trapped in an avalanche in Alaska. What he created in Man in Snow is an extraordinary, exquisite and poignant story of one man’s grief over the loss of his son, his questions about life and death, of love, of marriage, of parenthood that entertains and moves us profoundly and even to tears.

And I must digress here to praise the lighting and scenic designs – a white circle on the floor with a central square, an ordinary white wooden chair, and a backdrop of white transparent material draped to suggest icy snow designed by Jenna McFarland Lord complimented wonderfully by the colorful and vibrant northern lights effects created by Niluka Hotaling. And onto this stark and innovative vision, the audience is bidden to imagine the world of snow and freezing temperatures.

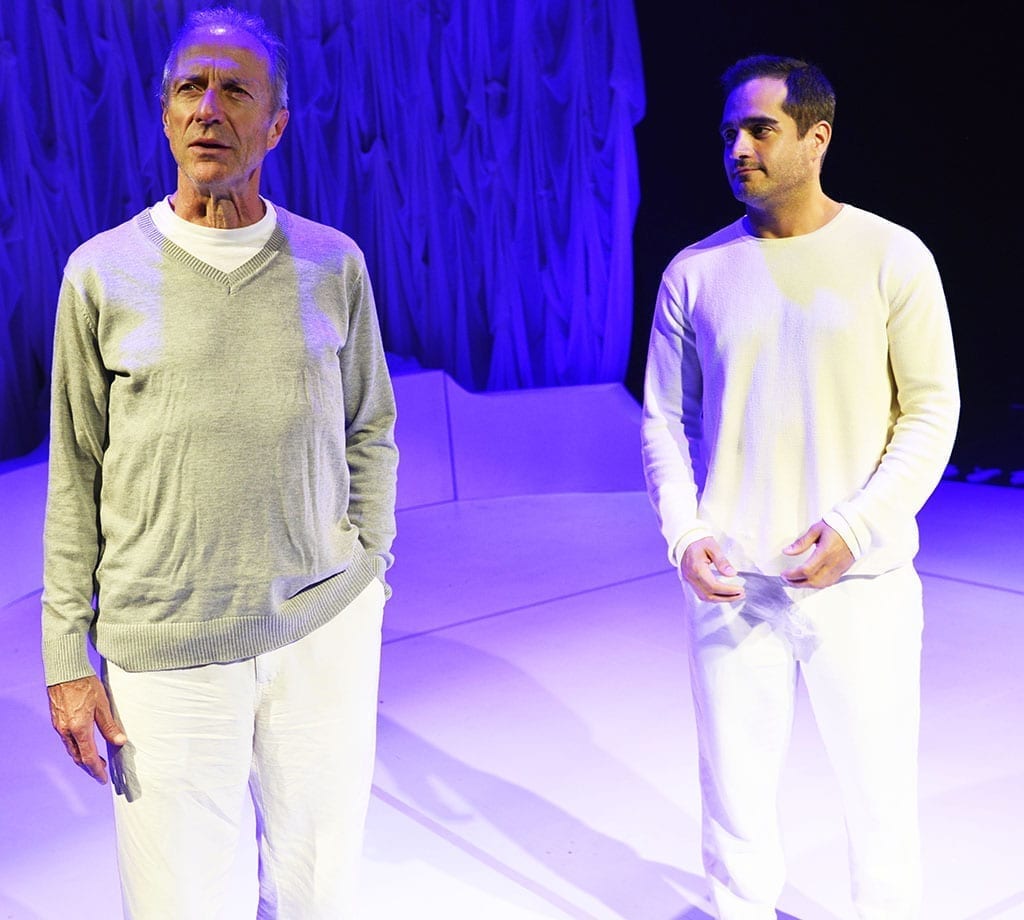

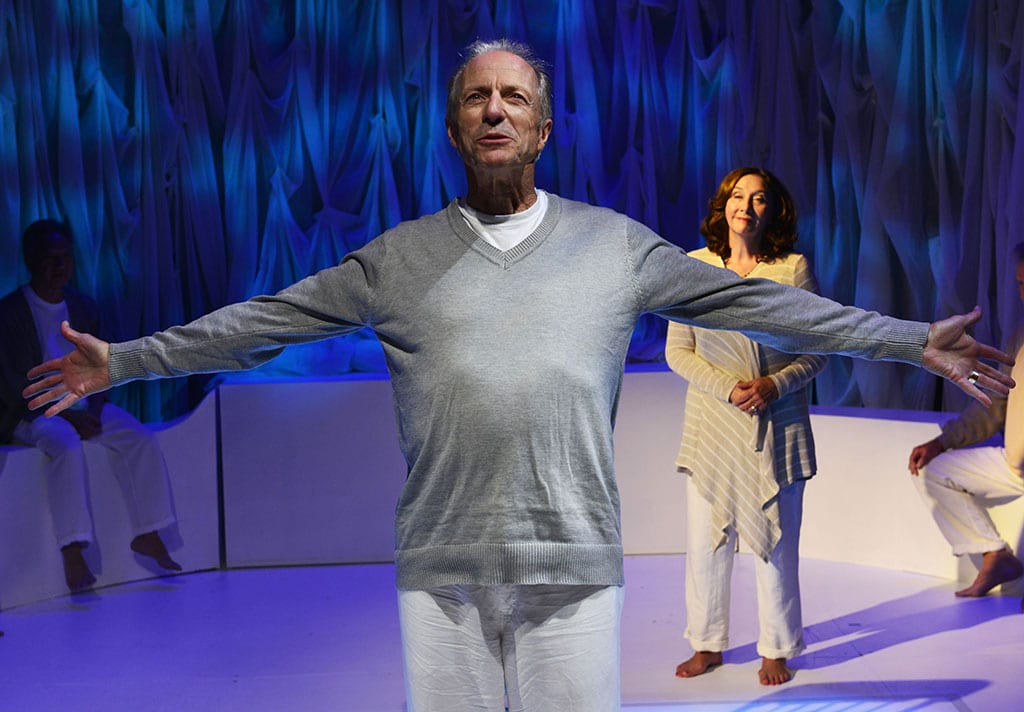

The plot concerns David (played with remarkable depth by Will Lyman) who has returned to Alaska and Mt. McKinley (now renamed Denali) to lead a group of Japanese honeymooners to experience the northern lights. They want to conceive their first child under the influence of how David refers to the northern lights as “tumbling out of God’s mouth.”

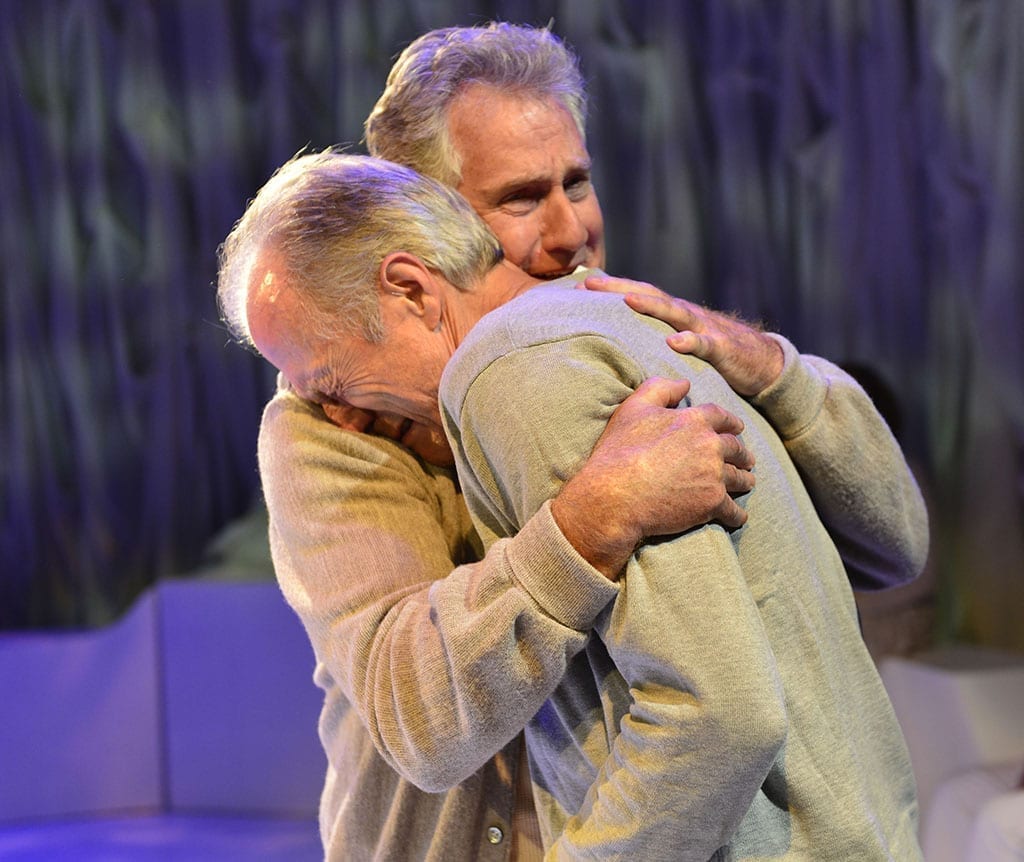

David is there not only to guide these Japanese newlyweds but to come to terms with the loss of his son, Joey (Francisco Solorzano). He is haunted by the stultifying guilt he feels as a father who outlives his son, by his relationship with wife and daughter, by deep religious and existential questions. “Why am I alive?” he asks the Joey in one of many visions he has of his son in the afterlife. He is connected to his family (Sandra Shipley, his wife, Ashley Risteen, his daughter and Paul O’Brien, his cousin – all with superbly nuanced performances) by cell phones as well as his re-enacted memories of the good and bad times of their life together. One of the many outstanding and powerfully heartrending scenes is between the two men as David’s cousin tries to comfort the bereft father who has lost his son to a motorcycle accident.

To assuage David’s grief, his family comforts him with words that do not quite satisfy what is left after grief devours a parent. Enter Mr. Takayama (Ron Nakahara), an 89-year old Japanese man who has been coming to experience the northern lights since his own honeymoon. He does not offer easy consoling words to David’s “blinding grief.” His advice is that one must find strength and purpose in the sadness that comes from loss, and think of how to use the time we have left, and that life is the same whether we spend it crying or laughing. Mr. Nakahara’s serene performance, tempered with moments of self-aware humor, wards off any suggestion of some smug Zen-like answers to the mysteries of life and death.

Mr. Horovitz originally conceived of this as a radio play for BBC Radio 4 in 1999, and then developed it in workshops and various performances in Italy with Compagnia Horovitz-Paciotto and here in the U.S. with, among others, Gloucester Stage Company, whose production we now have here. The care in development is well reflected in the artistic and emotional gratification we receive from this superb production. At 77, Israel Horovitz, still vital in his originality, has created in Man in Snow a piece that confronts our imagination, challenges our fears and complacencies and is, finally, immensely entertaining and heartwarming.