Among Kenneth MacMillan’s many distinctive and famous ballets Mayerling continues to win the highest plaudits, and justly so. More than any of his other full-length works this three-hour masterpiece combines his talent for dramatic narrative with searing character-study. No decorative surfaces or purely pretty patterns here. Instead we are plunged into the contrast between the stifling constraints of the late nineteenth-century Habsburg court in Vienna, and the desire for self-expression of the Crown Prince Rudolf who seeks, without success to break free from both the artificiality of hierarchy and formality and find a love and consolation he is constantly denied, particularly by his remote mother, the Empress Elizabeth. Though the narrative sticks close to history, culminating in the murder-suicide of Rudolf and his young lover Marie, it also evokes the emotional framework of pre-existing ballet classics such as Swan Lake, where formal ritual and refinement are also juxtaposed with melodrama and neurotic extremes. There is darkness and complexity within a wholly engrossing narrative frame.

The music that accompanies this story is an arrangement of many less well-known pieces by Franz Liszt, expertly combined by John Lanchbery. You might think that the milieu of Strauss waltzes and Tchaikovsky would have been the most natural fit for this material, but in fact the blend of delicately shaded private melancholy and brash Hungarian brilliance uncovered here is exactly right for the extremes of emotion unveiled across the evening. The Royal Opera House Orchestra under Martin Yates give an expert account of the score despite the constraints of fitting the rhythms to the convenience of the dancers.

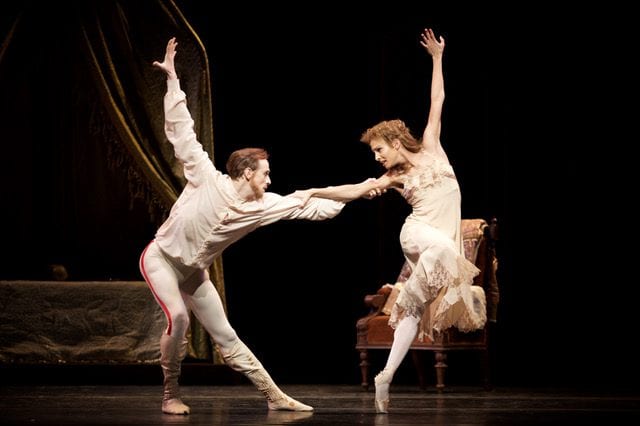

In this latest revival Edward Watson returns to a role that he has made his own. Never one to play the conventional swaggering prince, he is able to convey both the despair and sensitivity of the lead character with a continuously poignant grace. Yet he also harnesses when needed the reckless physical abandon and sense of danger that is the other side of this doomed character. Much of the ballet consists of an engrossing sequence of pas de deux between Rudolf and the women in his life that are exceptional in their expressivity. His dancing with his icy mother Elizabeth evokes uncomfortable memories of Hamlet’s scene with Gertude, and the arm movements deployed here by Zenaida Yanowsky are a remarkable elucidation of emotional coldness. The choreography becomes all the more convoluted as the action progresses. The final scene of Act 1 in particular between Rudolf and his unloved bride (Francesca Hayward) is disturbing to watch as violence and self-hatred are transformed into kinetic equivalents that still make uncomfortable viewing. Sarah Lamb is consistently fine as former mistress Countess Larisch, dancing with great emotional lucidity, and Natalia Osipova has all the technical bravura needed for the role of Mary Vetsera, though she seems at times more knowing than innocent in her approach.

Beyond the central characters there is a delightful attention to detail, whether in the sequence devised for the Empress’s maids or Rudolf’s joshing dances with his Hungarian officer friends, which bear comparisons with the graceful freedom of the sequences for Mercutio and his associates in Rome and Juliet. There is plenty of humour too of both an innocent and gallows kind, as Rudolf toys with skulls and revolvers and a brothel scene echoes Cabaret in its saucy playfulness.

Nicholas Georgiades’ designs capture in a dark, gaslit glow the frumpiness of the well-upholstered palace interiors, and the exquisitely accurate period costumes are a reminder that while the Austrians may have lost many battles they still win the fashion parade of military uniforms and ballroom galas. There are some ballets that always have a frisson of anticipation around them and this is one such: in both technical daring and emotional extremes this revival does not disappoint. We have here a gripping account of heartless pageantry, both sumptuous and stiff, with a skein of hypocrisies held in a vice of vice; and alongside it wild, reckless and romantic self-assertion. Totally gripping from start to finish.