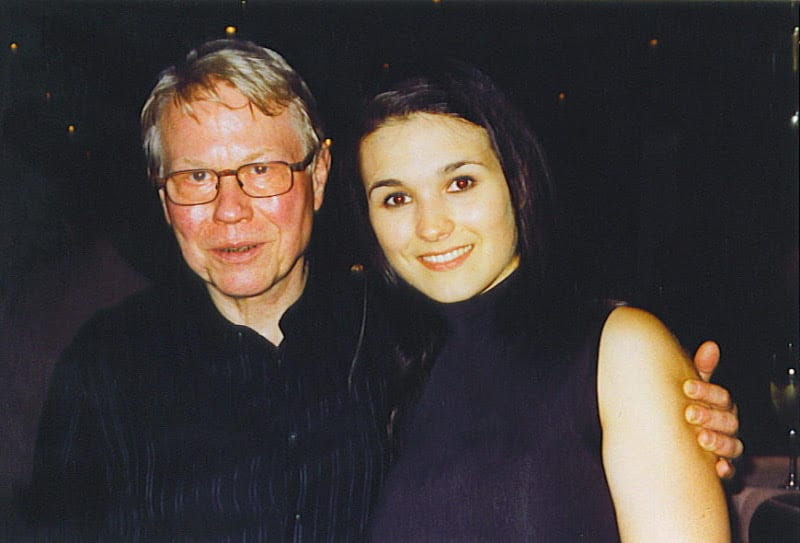

Olga Peretyatko’s debut performance as Norina in the current performance of Donizetti’s comic masterpiece, Don Pasquale, at the Royal Opera House is a triumph. Critics and audiences alike have consistently praised and delighted in her singing and her theatrically adept performance. We met at the ROH on her day off. The night before, her performance was filmed and screened internationally. I attended that exquisite performance and found it to be excellent.

Olga Peretyako’s Russian mother and Ukrainian father met in Kazakhstan, she told me, when we settled in for a coffee in a private room at the ROH. In those days both countries were part of the Soviet Union, so the idea of a clash of nationalities never crossed anyone’s mind.

Olga explained that she is one of three children. “I’m the only musician among my siblings. The other two are normal,” she adds with a laugh. Her mother worked in a bank and her father, a baritone, is still singing in the chorus at the Mariinsky Theatre.

As a young girl, Olga spent many evenings at the Mariinsky Theatre, loving the thrill of being able to watch the Orchestra and see her father singing in the famous chorus. For her, it was all magic sitting in the company box, above the orchestra pit. She was the only child to be allowed to be there. She still recalls with a tinge of her early excitement “the very first performance I attended at the Mariinsky. It was Gounod’s Faust”. In a way, that was her silent ‘debut ‘ at the Mariinsky theatre.

Her parents were divorced when she was just seven. She moved in with her mother until she had to return to St Petersburg for her musical education when she reached the age of 14 “because in Russia, they have this middle school before High School”. Once she started school in St Petersburg she studied from morning to late in the evening – all subjects with the additional extensive course in music. She also learned choral conducting. It gave Olga a solid foundation in understanding music. “All that was what gave me an amazing theoretical foundation and strong musical base, a real feeling both for culture in general and music in particular, for literature, and for everything about the history and theory of music. Everything, including analyses, solfège, harmony, everything; and that is what helps me so immensely till now”.

Olga started out as a mezzo-soprano only to discover, at the age of 22, that she is actually a soprano. Initially, it came as unwelcome news as she admired the powerful heroines, such as Carmen, and Amneris (in Aida). Three days of deep depression ensued after hearing the ‘bad news’ that she was a soprano and not a mezzo-soprano. She started listening to a vinyl record of Joan Sutherland. “Sutherland is the reason why I am singing today. Sutherland was my first inspiration,” says Olga, with tender warmth.

Olga moved to Berlin to continue her studies. She learned German in the first year, prior to sitting exams and taking on the courses that helped advance her musical training. “Germany offers free education and that is most attractive to young students. But you still need money to live on”. There were small grants and for Olga, it was an opportunity to sing in many student projects. “When you are young, everything is possible and you want to experience everything you can about your work” she points out.

At this stage, Olga and a string quartet composed of young musicians, organised concerts everywhere – in hospitals, hospices and churches – to earn some money, gain experience in front of audiences and to promote themselves as musicians. On one occasion, when they performed in a hospice, an elderly lady confided in Olga that she usually suffered from excruciating pains, but for the whole duration of listening to the music, she had had no pain. That was a revelatory moment for Olga; a moment in which she realised that music may be sheer entertainment for some but that it is a survival kit for others. She points out that some people may love a certain voice and others may think it is terrible. You sing for those who love your voice and it is okay, but one must respect that some may not share that view.

In Berlin, Olga chose Brenda Mitchell, as her vocal teacher. “I chose her because her name sounds English; so I assumed she could speak English. My German was not good enough at that point. Sure enough, she is Canadian, so English was not an issue. In fact, she speaks a few languages – French, English, German and Italian and that was a real discovery for me, and also, an inspiration. I realised that knowing languages is extremely important for opera singers”. Ms Mitchell offered Olga ‘soft’ support that helped the young soprano to establish her inner confidence. “She was always there encouraging me. She encouraged me, and all her students, to be very independent technically. ‘It’s your voice. It’s your body and you should adapt it all to your system, she told us. On stage you’re on your own, you’re the character you are projecting. You must not be distracted from your part and character, whatever else happens on stage”.

If there is chemistry between the team, (as it is in this production of Don Pasquale), then “we can change something spontaneously during a performance and the audience will not notice, as we react to each other. Occasionally, those you are singing with are more rigid and there is less chemistry between the team and the director can also be very rigid. They demand that everything should be just so, as it is in the rehearsals, with no room for manoeuvre”.

For the benefit of our readers, who are keen to understand a bit more of the real unfolding drama on stage but outside the actual text, Olga explains the importance of “a flexible conductor, who can breathe with you, follow you” to elaborate the point, she explains that singing bel canto offers freedom. That freedom can only function in the context of flexibility from the conductor and other members of the cast present on stage. Olga explains “Historically bel canto was born with three composers: Bellini, Rossini and Donizetti. Donizetti, in this case, is a bridge to Verdi. Verdi brought real life on stage and in La Traviata he chooses a scandalous character to be the protagonist. Later came verismo, and real-life stories and not just about kings and aristocrats, but normal people who are the protagonists of the opera. In bel canto operas you can play with the second strophe of the cabaletta and give your own variations, coloratura, low notes, high notes, however you feel. So it is up to your performance. It can change from performance to performance, too, and the conductor should react to your performance, as things can happen, you know, you can blackout, something falls, you are distracted, that is life and that’s why I love this because it’s life and the conductor has to really appreciate it. A good conductor is one that can breathe with you and follow you and practically be inside your throat with you. Singing is very good for your health too, like meditation. My mantra and my singing are good for my health!”

I asked Olga if she had any theory about the vocal cords, why some voices can sound so sublime.

“It‘s all about breathing, the energy of life. When we come to the world, the first thing we do is use our diaphragm. Learning to breathe properly is exactly what we should be doing,” she says candidly. Apart from yoga she finds saying her mantra another practice that helps her clear her mind and switch off irrelevant clutter and concentrate on what matters. “Mantra meditation came into my life like four years ago,” she says. “It helps to clear the mind.”

She tells me an anecdote that highlights the impact a voice has on children Olga was asked to speak to sick children at Casa Ronald McDonald in Valencia. She was asked to talk about singing and breathing and to tell them what it feels like being an opera singer. Initially, the children were not interested and were distracted by the electronic gadgets they have. The minute she sang a few high notes, every gadget was dropped and attention was totally engaged. “I told those children that we are super-human, that we can do jazz and pop music without using a microphone. Pop and Jazz singers cannot really perform without a microphone, while we can.”

Olga believes that one way to expose new audiences to opera is by inviting ‘people and school pupils’ to rehearsals, then they can see how it works, “because we are laughing and sweating or whatever. They see what can happen in rehearsals and never can be allowed in the performance and that can interest them.”

She won second prize in Operalia 2007. “The money was great, £20,000, which helped, subsidise flights and hotels for auditions.” However the most significant turning point in her career was not Operalia but the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro (Italy) that same year, 2007. The opening show of the festival was Rossini’s Otello. Olga performed the part of Desdemona. The title role sang by Gregory Kunde, and Rodrigo by Juan Diego Florez. And since then she has been travelling the world and appearing in leading opera houses.

Olga admits that today to be an opera singer is not easy. They expect you have to be young forever, beautiful, fit, to jog and be a good actress and singer. Before Maria Callas, she believes, a singer could get away with merely singing.

In Don Pasquale Olga performs the part of Norina, a woman that agrees to take part in a bogus marriage in order to manipulate the rich old man, Don Pasquale. Her aria ‘Quel guardo, il cavaliere’ makes no secret of her ability to use her looks, smile and lying tears (So anch’io la virtu magica…) to charm her way and fool the old man’s heart.

“Donizetti’s women are not easy at all. Just look at Norina in Don Pasquale and Adina in L’elisir d’amore. These are two female characters, which are not very simpatico. They can be cruel. They play with someone else’s feelings. The director Damiano Michieletto wanted to project Norina as a gold digger, a real bitch. I did not think that of Norina”. Olga wished to show her character in a more sympathetic light. She wanted to ensure that the audience does not feel her cruelty to Don Pasquale is gratuitous but for the good of his nephew, Ernesto, with whom she is sincerely in love.

Having discussed the character in great details with the director, he agreed to present the character more sympathetically. This production, with a different cast, was staged in Paris. In the Royal Opera House’s staging, Norina is not portrayed as a pure exploiter. She can be smart, manipulative, childish, knowing, but in principle, she is a good person. Once she slaps Don Pasquale, she realises that she has crossed a red line, but she cannot change, as she wants to make sure she achieves her goal. The real evil character in this story is Doctor Malatesta, in Olga’s opinion “as he manipulates everyone and Norina knows that”. Olga points out that she is very fortunate to work with Damiano Michieletto, the director of Don Pasquale, as he is flexible and happy to discuss each singer’s character with that singer. Initially, the director, Michieletto, contemplated a liaison between Norina and Doctor Malatesta, “making her a gold digger and a bitch and a double-crosser”. Following a discussion, they both agreed about the interpretation of Norina that Olga should present on stage. This Norina is not a female monster but a more sympathetic character, who loves to sparkle.

Olga lovs her time at the Royal Opera House. “Every day, six hours rehearsals for three weeks. I love it. I enjoy coming to work”

Olga, who has now appeared in many leading opera houses, finds La Scala a place of stress from the minute you enter stage door. Here, at the Royal Opera House, she says it is a pleasure. “Everyone is relaxed, though serious and committed but, work is made to feel real pleasure.”

She admits that she tries not worrying about two things – the acoustics of the building where she is singing and the audience. “You just have to give it your 200 per cent and that is it.”

In November 2019, that is next month, Olga will performing Lucia in Lucia di Lammermoor (Donizetti 1835) in Monte Carlo and on 28th and 30th of November she performs the title role in Anna Bolena (Donizetti 1830), at the Royal Opera House Muscat.

She is clearly doing Donizetti proud.