Verdi was a great admirer of Shakespeare, and would significantly contribute to the canonization of the Elizabethan writer in nineteenth-century Italy with his Macbeth in 1847, Otello in 1887, and Falstaff in 1893. By the time Otello premièred in Milan, Verdi had been unofficially ‘retired’ for sixteen years: he was enticed back to work in the opera by the editor Giulio Ricordi and the conductor Franco Faccio, playing on Verdi’s friendship with Arrigo Boito, who wrote the libretto.

This new staging of Verdi’s Otello captures Verdi at this late stage in his career, and brings to life an authentic, accurate, and acutely refined portrayal of Otello’s fall from grace — a fall which is cleverly mimicked by Otello’s own horror at his mirror image, alongside the gradual collapse of a huge statute representing the Lion of Venice which marches on proudly in the midst of the drama only to be reduced into fragments by the end.

Gregory Kunde, in the title role, superbly combines his magnificent singing to his fine acting. He realistically conveys Otello’s jealous rage after having been poisoned by Iago, played by Željko Lučić, who brings an impressive element of sophistication to the dark role, particularly during his evil ‘Credo’. Perhaps as a nod to the fact that Verdi and Boito had initially considered naming the opera Jago, this role actually opens the production. Indeed, the opening resembles more of a scene from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and, just before we see the outbreak of the storm (with the chorus huddled at the rear end of the stage who later break out into acrobatic dancing during the ‘drinking’ scene), Iago’s ghostly presence is fixed centre stage as his shadow permeates the entire action.

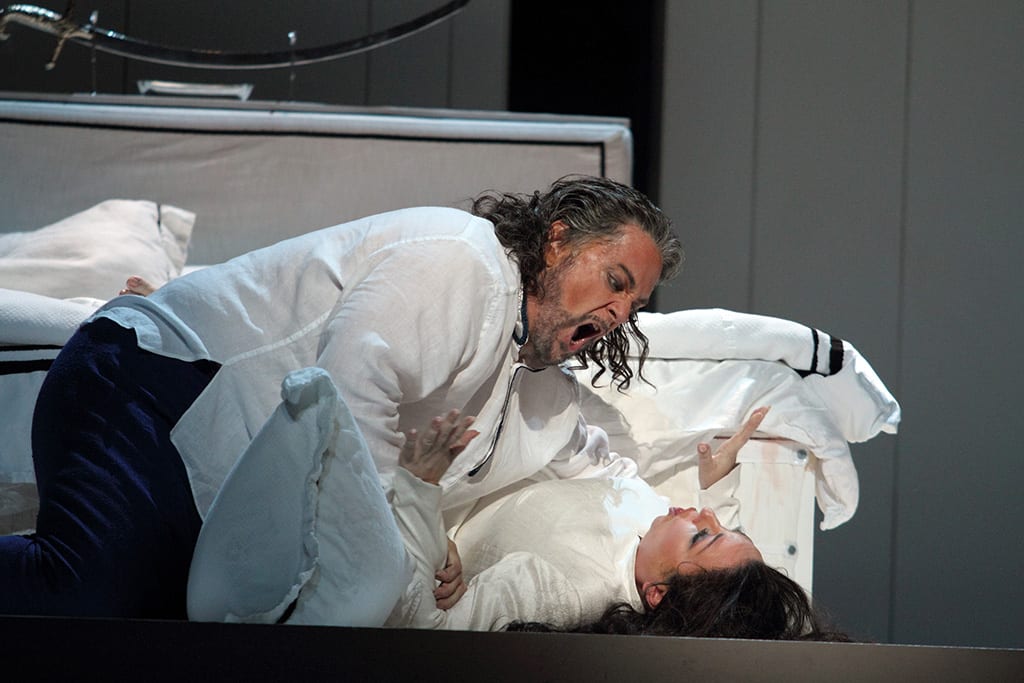

Desdemona is also powerfully portrayed by Dorothea Röschmann. Dressed in white to reflect her purity and innocence, her voice strongly reflects her character’s intense fear towards her impending tragedy, above all during the Willow Song, the Ave Maria, and her farewell to Emilia, performed by Kai Rüütel, who wears an unusual kind of head-ornament throughout the opera.

But what about the murder in Act IV? As we know from the publication of the opera’s production book or staging manual (the disposizione scenica), Verdi, together with Boito and Ricordi, took great care in providing exact details about the execution of this vital scene. Indeed, by the time the opera premièred, the role of Othello had gained notable critical attention on the Italian nineteenth-century theatrical stage owing largely to the passionate renditions of the star actor, Tommaso Salvini, whose violence during this scene allegedly caused some female members of the audience to faint.

It therefore comes as no surprise that the staging here, directed by Keith Warner, replicates the exact same intensity as the Verdi-Boito collaboration had envisaged. The production book, however, outlines more gory details, such as Otello dragging Desdemona across the stage, who, in vain, tries to resist. Despite this, the chemistry between Kunde and Röschmann, beautifully conveyed during the ‘Bacio’ scenes, is now conveyed as a bloody confrontation as Otello attempts to smother his wife. Likewise, Otello’s suicide scene is also portrayed with passion and realism, in spite of the inevitable use of fake blood smeared along the white sheets of the bedchamber as he tries to give Desdemona a final kiss: a glaring image which fades away into the darkness at the very end.

Pappano once more conducted a flawless orchestra who held the opera together with expertise and precision. This is a highly recommended operatic adaptation of a ‘simple’ story, based on Shakespeare’s own re-visioning of Cinthio’s Gli Hecatommithi (1565), which continues to move audiences today.