The 68th opera season in the Teatro Campoamor began in September with Die Walküre and continues in October with Nabucco, an opera first staged under its original name of Nebuchadnezzar at La Scala, Milan in 1842.

The libretto draws on biblical stories. Nabucco, King of Babylon, takes Jerusalem in his war with the Israelites – but his daughter Fenena loves the Israelite Ismaele. She frees their prisoners, leading her half-sister Abigaille to plot to take power.

Nabucco declares himself a god and is struck by a bolt of lightning. Abigaille tricks the now frail king into signing death warrants for the Israelites, including Fenena and Ismaele. Nabucco prays to the God of Israel for forgiveness; his sanity is restored and he saves the prisoners from death. He converts himself and his people. Abigaille commits suicide.

It has been stressed that the leading role in the Verdi’s opera Nabucco, the King Nebuchadnezzar, is a complex character, but, actually, his daughter Abigaille is much more complex. Abigaille is a character full of contradictions: she challenges her class (she is the daughter of a slave), her gender (she desires power, which is restricted to men) and defies the dominant ethnic group —from the story line point of view— (since she is an infidel). She only can redeem herself through death at the end of the opera.

Nabucco’s production in the Oviedo’s Teatro Campoamor underlines this interesting role as the center of the stage. This anti-heroine is dressed in red and, consequently, stands out among the widespread grey and black clothing on the other characters.

Moreover, the Russian soprano Ekaterina Metlova offers a decisive Abigaille despite the difficulties of this role. Her powerful voice achieves bright trebles and great mastery in coloratura and her brilliant Abigaille stands out from the rest of the cast’s characters. The audience recognized this in the final applause during the premiere.

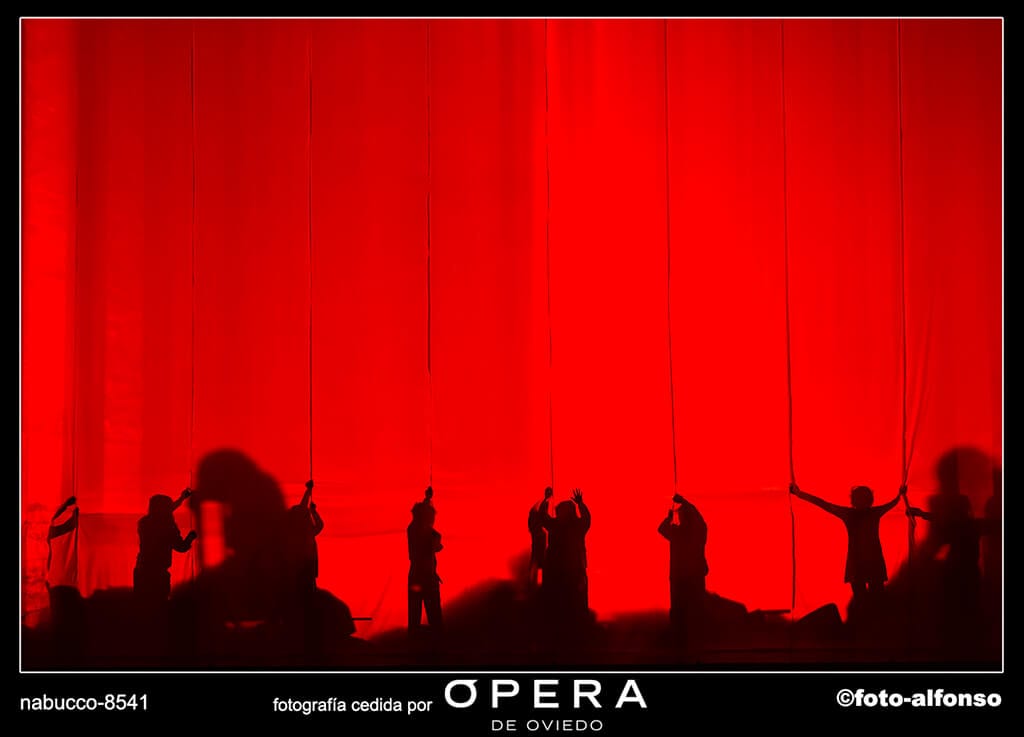

Emilio Sagi, the stage director, presents a minimalist and abstract scene that sets the action in a timeless frame. Wars, oppression and its consequences for people are topical issues and, at the same time, timeless. Sagi presents the action on an almost empty stage where different elements operate as symbols. In this regard, symbolizing Abigaille, Sagi offers a mural representing a fragment of Ashurbanipal bas-relief in which a fighter strong lion, though wounded, represents this woman, psychologically naked and full of fury and pain in her scena ed aria ‘In io t ‘ invenni…’

Stage direction and its components function as perfectly to serve Sagi’s concept and develop the plot with great clarity, through recurring elements of the stage director (for instance, the use of bright red and little lights holding on the dark stage), the staging of Luis Antonio Suárez, the gorgeous lighting of Eduardo Bravo, and Pepa Ojanguren’s costumes.

This production, made in co-production with the Teatro Jovellanos, Saint Gallen Opera, Baluarte Auditorium and Teatro Principal in Palma de Mallorca, unfortunately sometimes reveals a lack of funding apparent in little details that depreciate an otherwise elegant and effective work, for example, the structure that holds the beautiful Lamassu where Nabucco enters in the first act.

The skilled musical direction of the young Italian conductor Gianluca Marcianò offered a version restrained in tempi and, at the same time, very powerful: the Orchestra Oviedo Filarmonía played in a united and firm way, in which all of the instruments created a beautiful sound. The brass section and string bass in particular were excellent, especially during the ‘Preghiera’ (second act). Here, the bass Mikhail Russov offered his best in his role as Zaccarias. The Bulgarian baritone Stonayov improved as the opera continued, and shone in the aria ‘Dio di Giuda’. Sergio Escobar and Alessandra Volpe tackled the Ismael and Fenena roles well.The choir achieved the biggest success of the evening, together with Metlova. It offered really excellent singing, particularly in music in which the women’s voices were included, since sometimes music sung by the men only showed a lack of balance. On the whole, it was a performance with great force, which featured breath-taking moments (although perhaps too much pianissimo, as in the beginning of the famous ‘Va, pensiero’).

Reseña en español

La ópera Nabucco con que continúa la 68ª temporada del Teatro Campoamor de Oviedo ofrece una producción en que el personaje de Abigaille destaca como centro de la escena. Esta hija de esclava, que va vestida de rojo brillante sobre el escenario, resalta sobre el gris y negro generalizado del resto de personajes. A ello se suma la interpretación de la rusa Ekaterina Metlova, quien ofrece una Abigaille categórica en un rol de altísima exigencia. Su poderosa voz, de agudos brillantes y con gran dominio de la coloratura brindó una Abigaille brillante que destacó sobre el resto del elenco, y así se reconoció en los aplausos finales del estreno.

La producción es minimalista y abstracta, y no sitúa la acción en ningún marco temporal. El director de escena Emilio Sagi desarrolla la ópera en un escenario casi vacío en el que únicamente surgen elementos que funcionan a la manera de símbolos y que desarrollan la acción de forma muy eficaz. El coro fue el otro gran triunfador de la noche. Ofreció un recital de buen hacer, sobre todo en las intervenciones donde se incluían las voces de mujeres. La dirección musical del joven director italiano Gianluca Marcianò esgrimió una versión contenida en los tempi y, al mismo tiempo, de gran efectividad: la orquesta Oviedo Filarmonía destacó en un trabajo unitario y firme, de gran empaste, en que descolló la sección de metales y la cuerda en los graves, sobre todo en la «Preghiera» del segundo acto con el bajo Mikhail Russov, quien ofreció un Zaccarias aceptable.

El búlgaro Stonayov fue mejorando a medida que transcurrió la ópera, ofreciendo lo mejor de sí en su aria «Dio di Giuda». Sergio Escobar y Alessandra Volpe abordaron con solvencia los papeles de Ismael y Fenena. En conjunto fue una interpretación con gran fuerza, que ofreció momentos sobrecogedores tanto en el pianísimo –quizá demasiado, por ser casi inaudible- con que comenzó el célebre «Va, pensiero», como en el concertante con que se cierra el primer acto.