Rodula was nominated for International Opera Awards Director of the Year 2019.

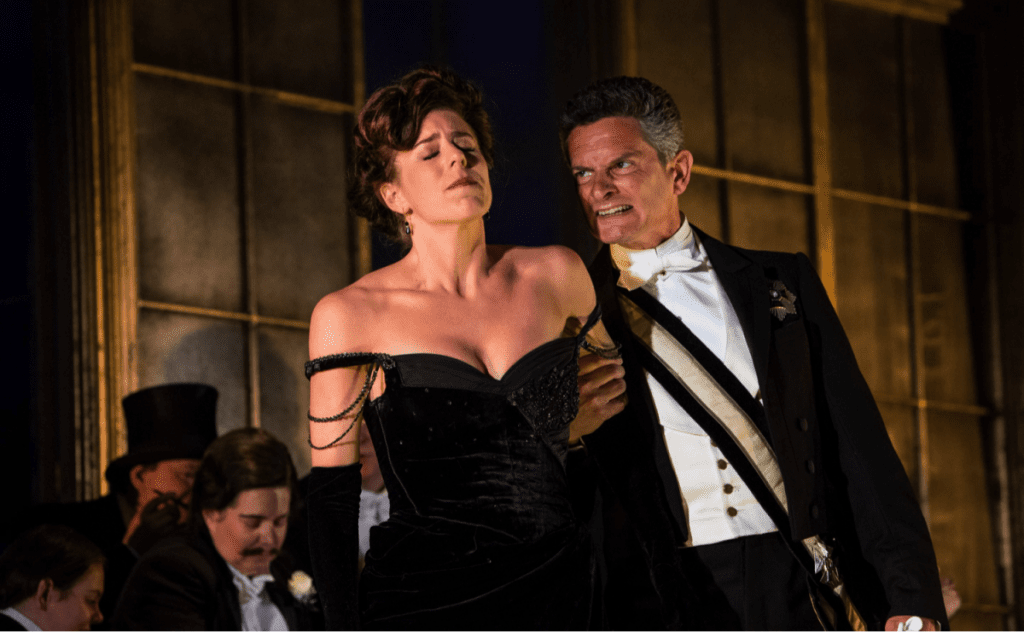

We met after I saw her magnificent production of Verdi’s opera Un Ballo In Maschera (A Mask Ball) at Opera Holland Park. This is the third opera she has directed for Opera Holland Park. The first two are Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades in 2016 was followed by Verdi’s La Traviata in 2018.

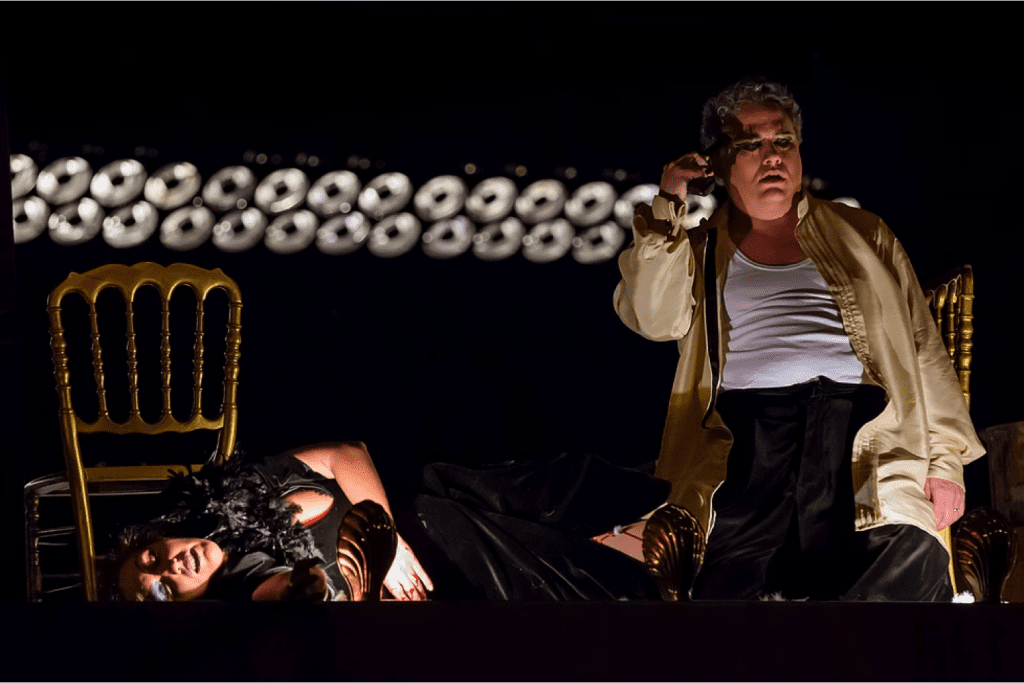

In 2016, The Financial Times, The Guardian and The Spectator praised the three leading performers – Natalya Romaniw (Lisa), Peter Wedd (Herman) and Rosalind Plowright (Countess) stating “compelling performances as three characters in the grip of obsession in Rodula Gaitanou’s staging of The Queen of Spades”.

In 2018 the critics loved her interpretation of La Traviata. David Mellor wrote “One of the most moving Traviatas I have seen.” Tim Ashley in the Guardian wrote that Rodula Gaitanou’s new production “opens not with Verdi’s prelude but with the alarming sound of laboured breathing, of someone gasping for air and life. It’s a provocative start to a thoughtful, troubling interpretation that carefully and insistently reminds us that the opera’s tragedy lies in its confrontation with encroaching mortality.”

She was born in Greece, studied in France and now lives in the UK. Her work has no boundaries, reaching out from Europe to the USA, Australia and East Asia, where she has also directed operas. Her two-year-old son has the score of Pagliacci imprinted in his DNA, having heard it before and after birth, when his mother directed three different productions of Leoncavallo’s popular opera.

She loves East Asia, China in particular, where she directed Tosca. In Xi’an, she directed the first ever-staged performance of a Western opera there. It was in 2015, in the oldest capital of China, in a city with 8000 years of history, ‘it was mind-blowing’. The newly built opera houses in the major cities reflect the Chinese government’s serious commitment to this art form.

It is clear from the current production at Holland Park that Rodula feels and appreciates the depth of the drama in the musical score and is able to merge it with the dramatic elements in the libretto, so I asked her about her musical training only to discover that she couldn’t have had a better start. She was born into a musical family. Her father was the artistic director of the Greek National Opera, her mother was a piano teacher and both her sisters are professional musicians one a viola player the other is a mezzo-soprano. She recalls that from the time she turned six her father took her and the young family to the opera, every night ‘which resulted in me being exposed to the art form from a very young age.’

She points out that conventional theatre was not exactly her scene; her passion and interest lay in the fusion of words and music. Rodula is adamant that an opera director must be able to read music. She compares an opera director who cannot read music to a theatre director who cannot read the text of the play he is directing. ‘One can have a taste for it, but you can’t really go under the skin of the piece if you cannot read music’.

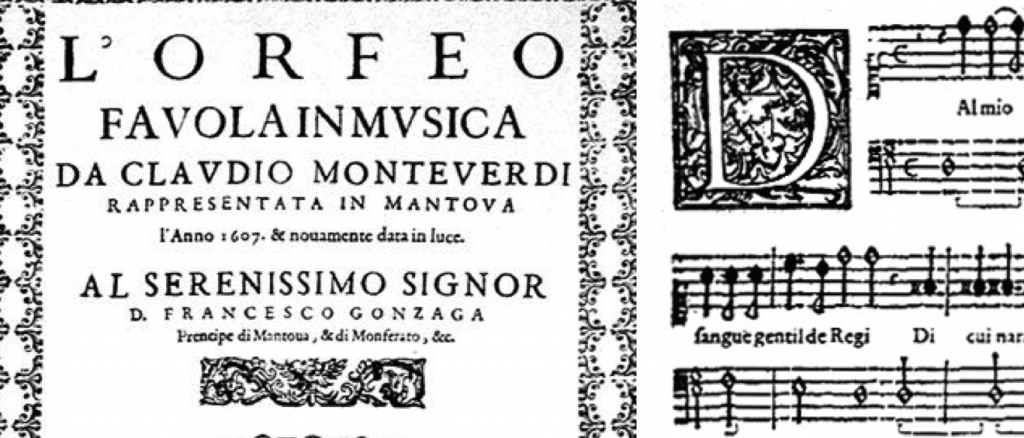

Rodula’s first challenging assignment was at university where she directed Monteverdi’s Orfeo but in its original form with no cuts ‘…which was quite an enterprise actually, because the means were scarce and we had to be extremely imaginative to create something out of nothing and as you know, Orfeo is a bit of an epic. It was great fun and it taught me a lot of things, and that was 17 years ago when I was 21. Then various projects came along, and despite the fact that I studied opera staging and musicology and did lots of internships at opera houses. I’m a firm believer that it’s a job that you learn by doing.’ She adds that the most important thing to know, for an opera director, is, of course, the repertoire, the pieces themselves.

Rivka: How do you approach a piece?

Rodula: I start from the score and I ultimately put the piece on stage. The music gives me a full sense of the drama while the libretto gives me only a 70% sense of the drama. I always start from the music and the first thing, before even reading the libretto, is listening to the piece. I don’t understand Russian, so if it’s in Russian I don’t understand the full meaning but I instinctively respond to the music. There is always an immediate reaction to the music itself. And then, of course, comes the marriage with the words and the music. The third level is visualising the world the music has evoked. You can have a big dramatic moment and usually one would expect the dramatic moment would be an extraordinary fortissimo or crescendo and often, the music suggests something different. I explore the drama of unspoken lines as in real life, and if you want the juice, it’s in what is not spoken most of the time – this is what I’m looking for when I study a score as well, it’s what’s in between the lines – what’s underneath, if you want, the musical layers’.

She then begins to explore where to locate the drama.

Rodula: For me, it’s all about storytelling. When we’re talking about the drama, it’s the drama of the characters that are involved; it is to find the perfect world in which to set the particular story. You can place the location everywhere and anywhere. For me, freedom is very interesting because it’s such a big, and radical choice. Cutting out all the options is the starting point for an idea to start forming.

In ‘Un Ballo in Maschera’, for example, there are so many places where you can place the same story. Rodula has the production open with a sword fight at a fencing school. She explains, ‘the actual opening chorus is such a beautiful moment because you have all these legato, piano lines. And yet there is this underlying, great sense of danger, which is there permanently and never really leaves the room, no matter what people are thinking’

takis the designer (and yes, he spells his name in small t), brought in the fencing because we were thinking of activity, she wanted it to be an athletic thing and I wanted it to be threatening

It is clear that the fencing idea hits the nail on its head. Rodula explains that the idea comes from the conspirators in the music, ‘ you’ve got these big legato lines and the conspirators first line which is very staccato, so immediately you create this contrast. And I wanted, from the outset, to have this sense of threat. That people are in a period of peace, and yet they are training to be able to kill. So it was the marriage of these two ideas – how can I get this great sense of danger in a peaceful setting, and how can I highlight what Verdi’s doing with the writing, which is creating this extraordinary contrast within the first ten bars of music. The very first idea I had for ‘Un Ballo’ was the masque itself, that allows you to mask gender, intentions, identities, so I wanted the masque to be a recurring theme and therefore the fencers have masks – you don’t know who your opponent is until the end, which is a great metaphor for what is happening at the end.

Naturally, this is teamwork. ‘At this point, the set, costume and lighting designer come on board. We put all the ideas under the microscope and we dissect them together. We throw everything in the mix and out of that come something, after a lot of work. We don’t crystallise the whole thing until after months of brainstorming. We are quite free in this process and honest with ourselves, so when we come out of it, there is something that is very solid. Before we start rehearsals we have created something that works both dramatically for space and the characters are three-dimensional. Most of the time I have a clear idea for what I want to do with the characters. Now this might be applied, this idea might work, it might not work. I might work with the singer who brings something so different, and so personal, and so enticing, that what I had as an idea doesn’t quite fit.

Events in this production take place in Sweden in the 1930s during a politically uneventful period to ensure nothing overshadows the narrative in ‘Un Ballo In Maschera’. Rodula wanted to focus on what she thinks is at the heart of the piece, namely the love triangle.

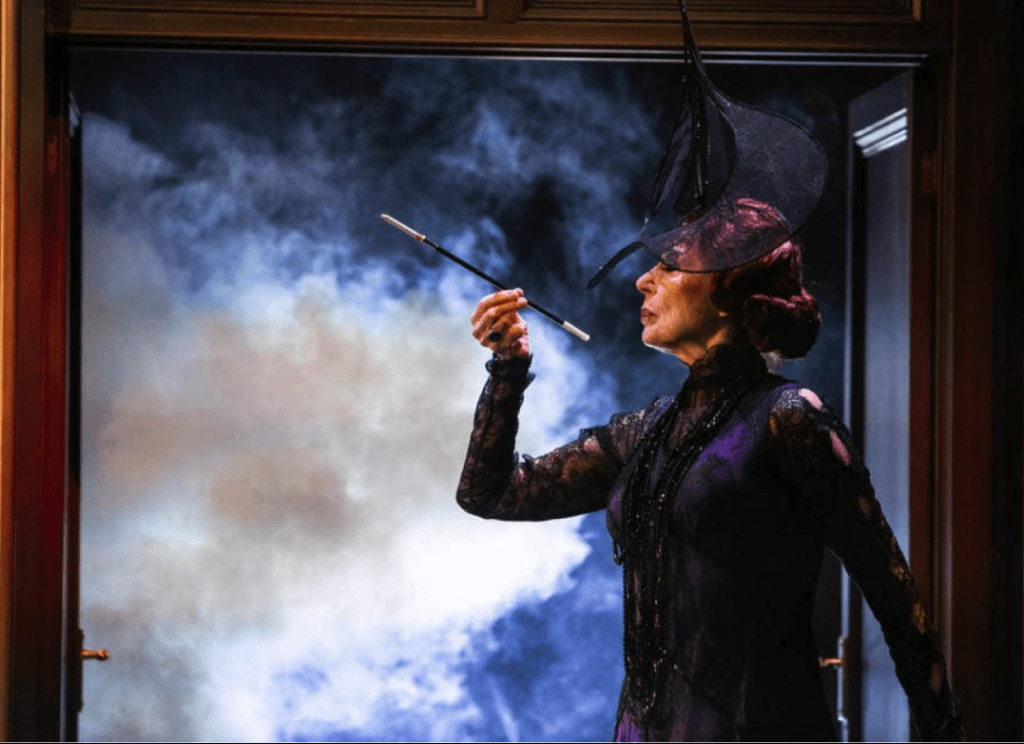

‘In addition, there is the conspiracy against the king, the fate element when the extraordinary character of the fortune-teller, Ulrica, Madame Arvidson. In our version, these three big narratives evolve simultaneously, and somehow meet at the end.’

Rodula’s approach to each opera she directs is a long process to ensure the audience is there for a very special treat. She assumes the storyline is familiar, hence she invests a great deal of energy and thought in the ‘how’ of telling of the story and how to generate the dramatic thrill from the music and the libretto, Rodula elaborates with an example from ‘Un ballo’, and explains ‘the moment you realise that Ankarstrom has caught his wife with the king, in a dark place, it’s as if he walked into his house and he finds in the bed his best mate with his wife. This is the situation, and if that happens in real life, it’s a bomb thrown into the room but it must be believable. And so must the characters be believable.

Rodula explains that there is no pattern as to how she creates the extra dimension of the characters as they always grow in her. For instance in Un Ballo, ‘it was clear to me that the king is very eccentric and not a natural-born leader. He is someone who is impulsive and emotional. Weak in the sense that he would always follow his instincts, rather than think pragmatically or realistically without engaging the emotional world and therefore he’s not a perfect king. The conspirators find a weak point on which they initiate this conspiracy. You don’t have a character that is being threatened just because the world is bad if that makes sense. And therefore, he becomes a completely plausible sort of person. You can see both his weakness and also the strength. He’s someone who is ahead of his time. He’s someone who sees through the situation. And he’s someone who’s bold enough to make fun when other people are completely gobsmacked, for instance. When Ulrica utters her prophecies, he’s not bothered by death. He’s welcoming death, in a way.

There are so many different ways that one can read the same moment.

We moved on to discuss the ‘comic’ character that defused tension and added humour in the unfolding dark narrative of this opera. It is the King’s page, Oscar, superbly performed in this production by Alison Langer. Rodula explains that ‘Verdi throughout the piece, has a foot in comedy and a foot in tragedy. So it’s a very fine balancing act. We go from extremely tense dramatic moments into things that suddenly lighten up the whole thing. Oscar is the only one we encounter – a woman portraying a man. The intention originally, I think, is to follow the idea of the masque and disguise the voice into a character that, for me, is very ambiguous. Is Oscar a woman or a man? It’s not a question I want to answer. It’s a character with many facets and has to be strong enough to hold the comic element.’

As to women in opera, Rodula thinks that opera somehow glorifies women and that this art form has treated women as characters extremely well through the centuries while other art forms didn’t

‘Despite the fact that these pieces were written by men, they put extremely powerful female characters at the centre of the story. So this is where I’m focusing on, I’m not focusing on the women being victims of the situation. They become victims if you tell the story of a victim’. Rodula explains that women have to comply with moral values and standards of the hypocritical society they live in, but once the story unfolds – her truth shines brighter. In this opera, for instance, ‘Amelia is the star but she doesn’t make an appearance for the first 45 minutes into the show and we have no idea who she is when she appears. She appears very frightened and she has just gone to a fortune-teller to know her fate, do you know what I mean? I feel that I need to take this character and ground her and give her a bit of background and context for her to be able to stay strong. And therefore I don’t see her as a victim, I don’t read her as a victim, and therefore she doesn’t come across as a victim.’

She explains that more often the female characters are much more rounded and complex. The male characters differ. The tenors for example – the hero, or the lover, can be mono-dimensional. “You have to dig deep to make them more interesting and a bit more human, so that they’re not just the lover. The same cannot be said about baritones, I have to say, they are complex, but that’s partly because they play the baddies. Baddies, you know, have more juice. I’d say that once more, opera has done justice to big female characters, and the female side.’

Rivka : What about the female characters assigned to mezzos singers?

Rodula: That’s an interesting question, I think the choice for the vocal type always comes with a choice for the colours that you want to have, and the different colours are always linked to intentions. So I think, undoubtedly, you do think of a character by putting a lot of things in the mix, one of them is exactly what sort of colours they bring, and what their music suggests. But a lot of the time, you have one thing said and another thing meant. Not always do they mean what they say, and the music is there to show you what they truly believe. I think the voice-type is undoubtedly an element that dictates where you’re going to take the character.

Rodula’s next big project is in Ireland, directing Massenet’s Don Quichotte. This opera opens the Wexford Festival Opera. Then another Un Ballo in Maschera, completely new production, different concept, different ideas, and different designing team, in Germany, in Oldenburg. Then, she’ll direct Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito in Bergen, Norway, and Carmen in St. Louis in the States. So it’s a busy season – very varied, very different pieces, very interesting, great colleagues, great teams.

Rivka: Un Ballo in Germany. The same music and libretto, but you’re going to put it in a completely new setting with a completely new interpretation to the characters. Surely there must be influences from your earlier direction of the same opera.

Rodula: Of course my appreciation of the piece hasn’t changed, how I’m thinking about the piece is different, but the world I am choosing and the way to tell the story – yes, they’re two completely different things. But my appreciation of the piece is, you know, what is at the heart of it, and what is primordial, is the same. And it cannot change really, you can have many ideas about the same piece, but I think the way you appreciate it and present it can be very different.

Rivka: Opera director and opera conductors – how easy or challenging it is to work side-by-side?Rodula: I love working with conductors, I love working with theatrical conductors because I’m a very musical director, I think, so that is the happiest of circumstances, is when I work with someone who has a very strong sense of theatre.

Rivka: I would have thought that the conductor interprets the music.

Rodula: Totally, but, you know, what the music is, is music for a dramatic moment or situation, so when you’re what I call a theatrical conductor, you have a sense of the pacing, of the drama – it’s not just about a choice of the tempi, you know, the choice of the tempi relates to something that’s happening on stage. In this decision-making, we very much work closely together and the conductor can facilitate the impact that a moment can have, and I can facilitate what he or she wants to do with the score. So we work so closely together, and he/she is my best ally on the floor. And I hope it is how they see me.

Rivka: So you start with the idea, you relay it to the conductor, then what?

Rodula: It is a constant exchange, a constant dialogue, so the conductor wants to do this slower, and maybe go into a pianissimo, which suggests dramatically the focus becomes smaller. To enhance his, or her, idea, I really need to put that moment on stage as well – I really need to find an intention for the pianissimo. It comes across best if what you hear translates to what you see on stage.

It was a tremendous pleasure talking to this exceptionally talented opera director.

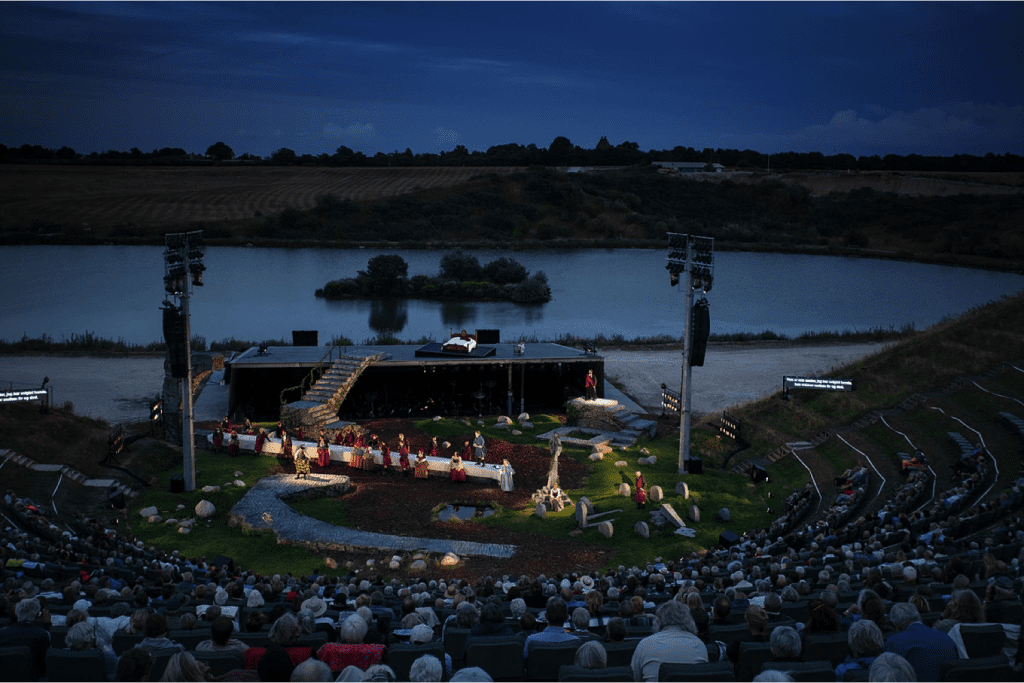

Her production of Lucia di Lammermoor was nominated for Best Opera Production in the CPH Awards (Denmark 2019). Her production of Barber’s Vanessa was nominated in the Irish Times Theatre Awards in the “Best Opera” category (Ireland 2017). She was nominated for two Helpmann Awards (Australia 2013) in the “Best Opera Director” and “Best Opera Production” categories for her production of L’isola disabitata presented at the Hobart Baroque Festival.