Ibsen’s 1886 Rosmersholm might well be his masterpiece, and in retrospect it may have inspired Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca.

Such a choice of repertoire must inevitably, therefore, be daunting. This production is a collaboration: the director, scenographer, and composer are Ukrainian, while the actors are Hungarian ethnics employed by a state theatre in Romania, acting in Hungarian.

The text is heavily adapted. It eliminates the strong social and political undertones of the original and plays down the religious crisis. It does away with Brendel’s and Mortensgaard’s subsidiary characters and practically becomes a boudoir play, with aggressive sexual connotations and images.

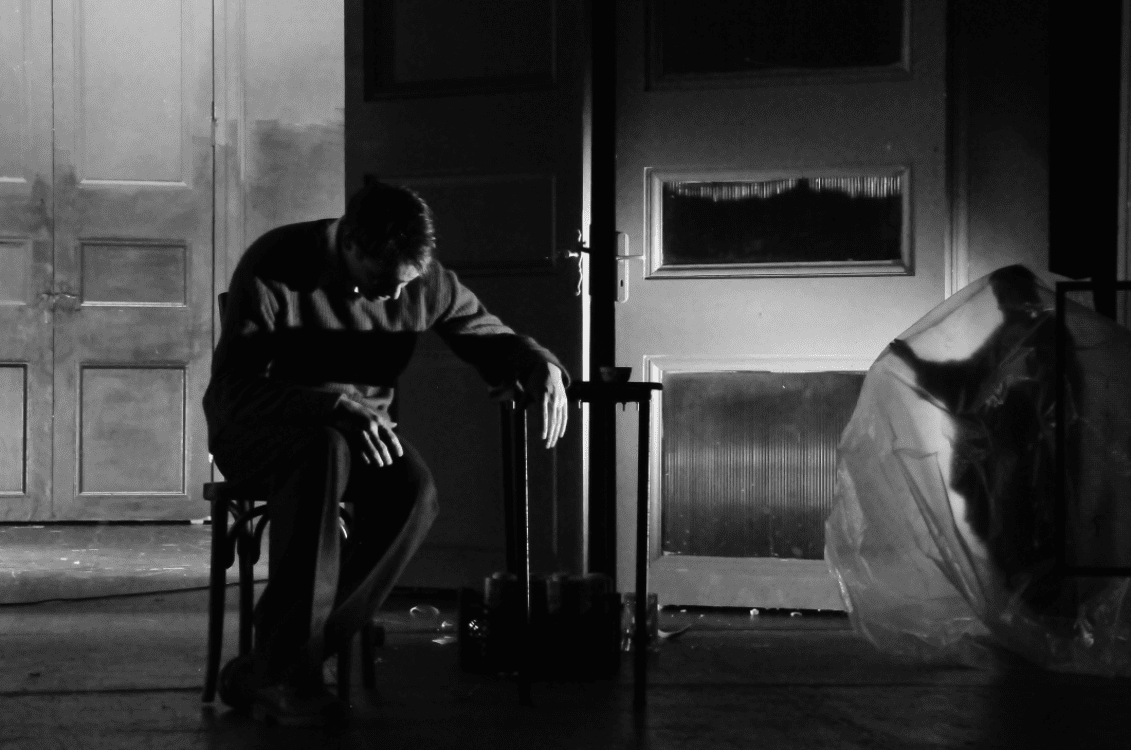

The scenography is extremely clever: the chapel is upstage left, adjoining the hall to the right. Downstage left a window opens onto the sea and there is a flower vase on the sill. The table is centre-stage, while upstage right there is a fireplace. This partition of the space allows for a captivating and fluid movement of the action. Everything is grey in this ugly world of murder, suicide, and incest.

The sound track of the production is greatly inspired and perfectly synchronised with the performance. The sound of the sea is its permanent phonic background, while the pre-recorded steps of the characters form the oppressive and ominous impression that each step weighs upon destiny. The noises of the trams and planes are added to fit with the temporally muddled view of the production.

In Andriy Zholdak’s conception, the action is not so much atemporal as pluri-temporal. Cell phones, laptops, CD recorders, and video cameras create a contemporary visual technology to match the phonic one. Rebecca strips several times, Kroll tries to rape her, then breaks a tea set, while Mrs. Helseth, the housekeeper, shakes her, in a preposterously inappropriate social gesture.

The production is also pluri-denominational, pluri-national, pluri-cultural and pluri-lingual. The chapel statues are Catholic, in spite of the fact that Ibsen was raised Lutheran and Norway is 71.5% Evangelical. Rosmer, a former pastor, makes the sign of the cross in Orthodox fashion and there is a pantomime of an Orthodox wedding (pertaining to the Romanian and Ukrainian denomination).

Certain passages are delivered in Hungarian, Romanian and English, and Rosmer complains he cannot utter the whole text trilingually.

The local colour is supposedly added, but in a truly illogical and clashing way: as the audience take their seats at the beginning, Rosmer and Beate (his dead wife) yell and move in a heavy and graceless dance to a Romanian tune from the North.

The addition of this phantomatic character is not a bad idea. She is dressed in white, as ghosts are wont to, while Rebecca is dressed in black – for murder and mourning, perhaps, in the hope the opposition does not stand for good versus evil.

Incidentally, West – Rebecca’s surname – cannot have been a random choice, as it is synonymous with occident, which literally means “killing” in Latin.

There are many cheap effects in the production, such as a lot of vulgar swearing in Romanian – the audience’s language – which inevitably triggers laughter when nothing is funny. Rosmer howls like Red Indians, eats his soup one metre away from his plate and throws up over Kroll, while Mrs. Helseth pours the soup in Kroll’s lap.

The performance is interminable, with more-than-ten-minute-long spans when not one word is uttered. Conversely, when there are large fragments from Ibsen’s meaning-laden text, they are delivered fast-forward style, as in medicine commercials, cancelling their significance.

There are several inspired ideas too, such as the permanence of plastic foil on stage, which symbolises the wrapping-up of a way of life, of a culture, of a religion; it stands for ephemerality and the loss of faith and morality. The acting’s intensity, meanwhile, bears witness to the greatness of the Russian School that formed the director.

Éva Imre is extremely talented and creates a haunting character. Unfortunately, Balázs Bodolai is quite hollow and superficial. Gizella Kicsid, Miklós Bács, and Tímea Jerovszky are solid actors who are convincing on stage.

The performance is hard to follow and to bear. On their way out, the spectators are however left with one great satisfaction: that of having seen one of the greatest masterpieces of the world repertoire.