This elegiac but rigorously unsentimental play with music received fine reviews in Manchester at the start of the year and now comes to Hampstead for a short summer run. It is a one-man show, with Will Young at its centre, surrounded by carefully calibrated production values that taken together should ensure a repeat of previous success.

We find ourselves in an antiseptic hotel room in Amsterdam, with high windows, a coldly neutral beige decor, and furniture that strives to be chic without personality. The style is ‘international’ in a way that appeal to and offends nobody. Ceiling and lighting levels and curtain widths alter as the eighty five minutes of the play progress, and snow falls; but that is all. The focus is very much on the meditative figure within.

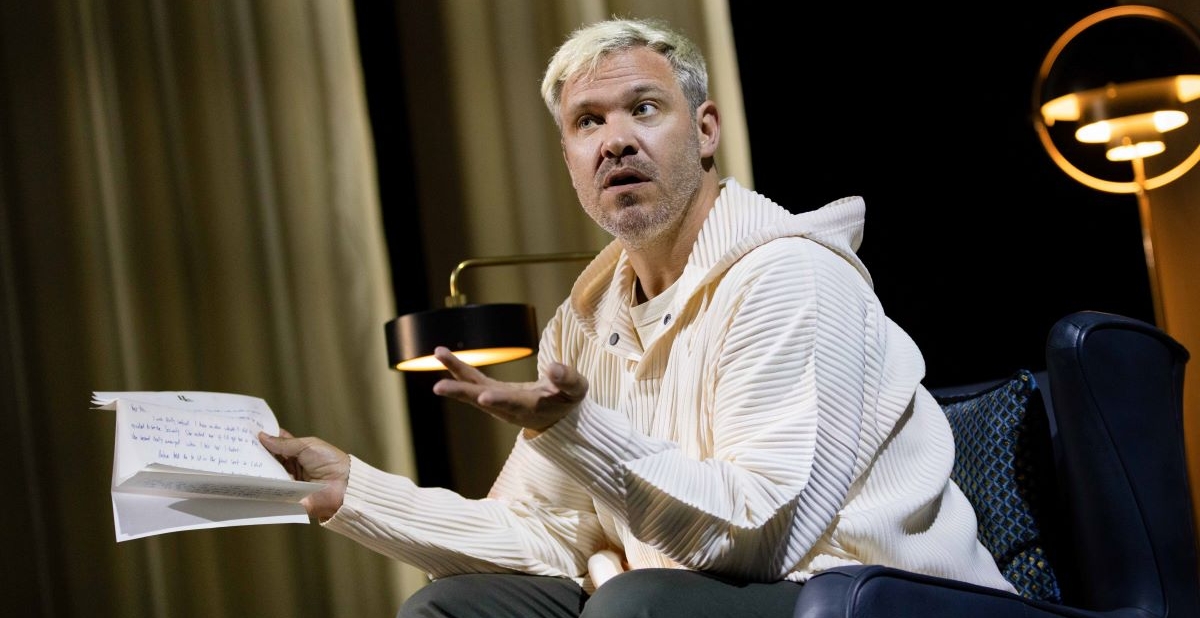

Willem, played by Young, is a deliberately unappealing figure. Originally from Holland, but long-term domiciled in New York, he is some kind of hedge-fund manager; clearly successful, but also restless and unfulfilled. He is more focused on the selfish pleasures of the moment than on deep reflection, and appears to have few deep emotional connections or social affiliations. As the play opens we find him reading a letter, one of a series he has written to his recently deceased brother, Pauli. It is Pauli’s death that has summoned him back – reluctantly – to Amsterdam, for a funeral, a reunion with parents and sister with whom he has uneasy and unresolved relationships, and above all to a reckoning with and appraisal of his past.

Where this play is unusual is in its avoidance of any obvious cliches surrounding grief. The emotional spectrum on offer here is quite narrowly restricted. While memory, anger, remorse, acceptance and several of the other familiar ‘stages’ of mourning are referenced, the character’s self-absorption and superficiality inhibit any deep explorations, at least until the very end where song takes over. Willem’s connection to his relations remains coldly, if sharply, observant, and we never in fact learn much about his brother, other than that he was artistic and lived at home with their parents. There is more focus on his reunion with a former partner and picking up a nightime companion to keep isolation at bay.

The pay-off comes at the end when Willem has a vision of his brother as he heads back home through the departure lounge at Schiphol airport and we finally receive a sustained, rather than fragmentary song sequence. All suggesting that song as opposed to speech is the medium through which not just Willem, but all of us, feel most deeply, tapping into our deepest emotions. Given Young’s prowess at pointing and putting across a song with delicacy and precision, this is a finely achieved climax, a place of genuine poignancy, all the more so because it is held back to the end.

To hold the stage through a kaleidescope of moods for eighty minutes is no mean feat. We are reminded rightly of Young’s skills as an actor just as much as his talents as a musician. It is to be hoped that he will continue to mine this aspect of his talents in future productions. He certainly realises the full potential of this role, and the play offers a perceptive vignette of Amsterdam in unforgiving winter light, and a bleak world of gay regret reminiscent of Anita Brookner’s keenly observed, minor-key novels.