When Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring was first performed in Paris in 1913, the score and choreography were so controversial that they provoked riots. The original choreography is now lost, but tonight’s performance pairs Stravinsky’s music with contemporary work by Christopher Hampson, Artistic Director of Scottish Ballet, in double bill of Stravinsky’s work. So how do you create a balanced double bill with such an infamous piece? To put it simply, you go for contrast, and The Fairy’s Kiss, a subversive twist on neo-romantic ballet, choreographed by Sir Kenneth MacMillan, does exactly that.

The Fairy’s Kiss was first composed as an homage to one of Stravinsky’s favourite composers, Tchaikovsky, famous for his romantic ballet scores including Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, and The Nutcracker. Stravinsky’s homage features all the sweeping sound of these classics, with full orchestra sequences, and delicate harp solos, all handled elegantly by Jean-Claude Picard’s orchestra. The Fairy’s Kiss is so rich with quotations that Stravinsky soon couldn’t tell which notes were his own, and which were Tchaikovsky’s. The ballet is an adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale The Ice Maiden. The narrative features a young man (a perfectly cast Barnaby Bishop Rook) who is kissed by a fairy (an absolutely captivating Sophie Martin) as a baby. She returns, on the eve of his wedding to a young village woman, to claim him for herself. The themes are rather traditional – love, temptation, betrayal – as are the costumes. The fairy’s glittering white tutu could easily be worn by Odette or the Sugar Plum Fairy, except that unlike these characters, she is not benign. Each pas de deux she has with the young man mirrors those he has with his fiancée, but with sinister departures from the classical canon, twining her body about his until he is bent double beneath her, in her thrall.

Scottish Ballet uses Sir Kenneth MacMillan’s little-performed 1960 choreography, painstakingly recreated from archival video footage. MacMillan is ‘always disruptive’, says Hampson, and while the performance features signature moves made famous in his later ballets, they are full of quirks that destabilise the classical style and themes of The Fairy’s Kiss. Gary Harris’ set design echoes this narrative, the performance starts with a snow-covered mountain and the fairy’s icy entourage. Thereafter, wooden window frames and other set pieces cover the mountain, disappearing scene by scene, until we’re left with nothing but the mountain once again. This production is stunning, nostalgic, and subtly subversive.

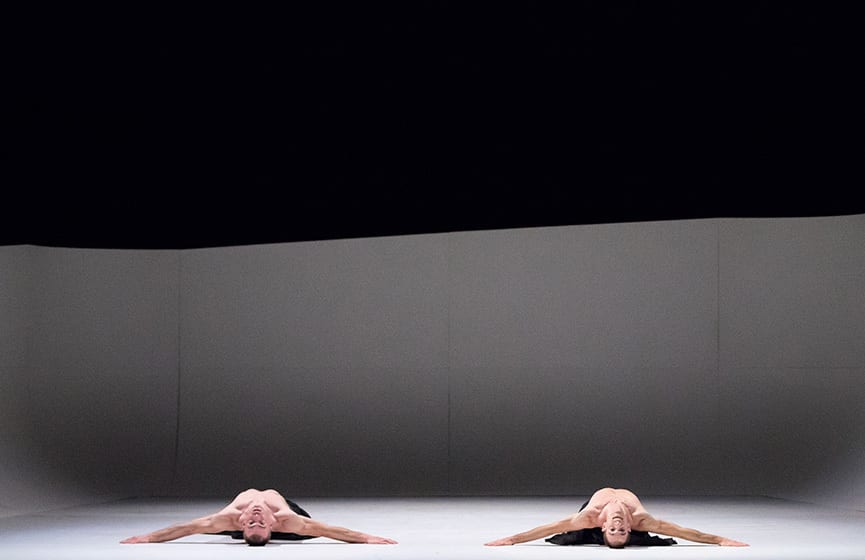

Christopher Hampson’s version of The Rite of Spring, on the other hand, is a harrowing exploration of power struggle and abuse – both physically and psychologically violent. Two brothers dance on a stark white stage, hemmed in by three white walls. They wear nothing but sweeping black trousers that billow as they move. Their playfighting becomes more and more combative, as the older brother dominates the younger one, and wears him down. They ritually cover one another’s eyes, come together and apart, run up the walls, their movements compulsive, repetitive, with the older brother (Victor Zarallo) becoming increasingly violent, the younger brother (Jamiel Lawrence) weaker, using looser, exhausted gestures. A woman who represents faith and death weaves in and out of the narrative, offering hope, then escape. Zarallo exudes toxic masculinity – though his military uniform in the second half is heavy handed. Lawrence’s performance shifts subtly from playful, to desperate, to hopeless. A deliberately uncomfortable piece, this is a perfect compliment to The Fairy’s Kiss. Hampson’s take on The Rite does away with the large original cast and replaces it with something that may not be riot-provoking, but is certainly still shocking, and will have audiences captivated long after the curtain falls.