BUTA FESTIVAL OF AZERBAIJANI ARTS

As I walked through the blinding light into what was once an old dairy factory in Battersea, I had no idea what to expect from ‘Telescope’. All I knew was that the play was written by the prolific playwright and Azerbaijani Deputy Prime Minister, Elchin, and had been translated and adapted by Aloff Theatre Company. Despite his government career, the play seems quite devoid of Easter European and Western Asian politics. Instead, ‘Telescope’ explores what it means to be human. What happens when you die? Is there a God? Will those I leave behind mourn me? The script seems to retain a loyalty to the Azerbaijani original while also connecting with a contemporary London audience. Frequent mentions of Baku did not alienate or divide the multi-cultural spectators but rather connected them. We are all human, after all.

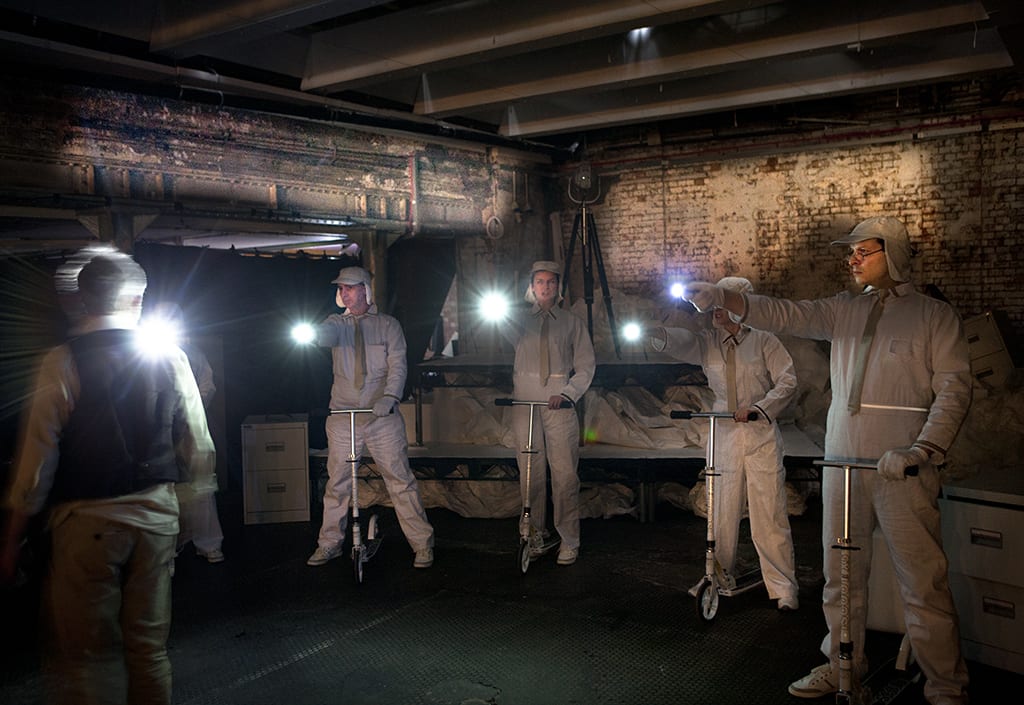

The play begins with a man (whose name is never mentioned) dying. Doctors and family members, played by a talented ensemble cast, surround him in anguish. The man slips into a coma, finding himself with his previously deceased ex-wife. She explains that they are in the ‘waiting room’, where they must stay until the angels decide where their souls belong: heaven or hell. In this resourcefully reimagined production, the angels are bureaucratic leaders, clad in white, with dozens of filing cabinets full of millenniums of paperwork and daily meetings in which they report their progress with the backlogs of the dead who are awaiting their final destination. Oh, and they travel around on scooters.

Chris Simmons gives a captivating and energetic performance as the man who finds himself hovering between earth and heaven (or hell). He deals with his character’s Kafka-esque anxiety with control and nuance. Tanya Franks balances her surreal command with a moving naturalism, creating a deeply likeable character. She is simultaneously both the man’s ethereal guide through the ‘waiting area’ and his loving, argumentative ex-wife.

Gould’s creative adaptation has the audience working as hard as the actors and characters. By the end of the show, your back aches from sitting on a white padded stool. You are forced to crane your neck to see different parts of the space and shield your eyes from the blinding lights being shone in your face. But it is not just your body that is sore once the show ends; it is your mind too. The hero is given an ultimatum (I won’t spoil it). The playwright, Elchin, asked his daughter and wife which of the two options they would choose if in the same position. They answered differently. As a result, the play has two alternative endings. In Gould’s adaptation, the audience is asked to decided the fate of the hero. Forced to confront our opinions on the afterlife and our assumptions on the humanity of the world, the play succeeds in questioning what it means to be alive.

The man decides he no longer wants to look through the telescope that allows him to see the world he left behind. The characters ponder that, in a world filled with such misery, can anyone take pride in being a human being? However, two young children sat opposite me in the performance. They were fully immersed in the world of the play; engaged in every step of the man’s journey. Their delight and involvement reinstalled my hope that perhaps we can be proud to call ourselves human.