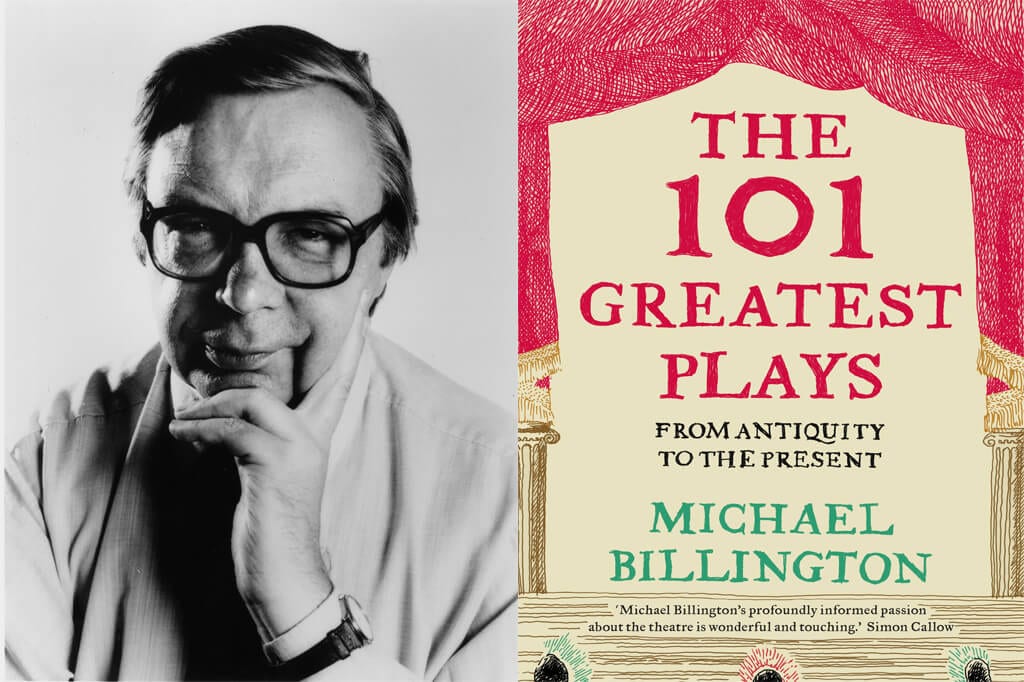

Michael Billington’s selection of his top 101 plays, from Antiquity to the Present, is a treat worthy of Trimalchio. Surely King Lear will top the fare or, if not, Hamlet? As it happens Shakespeare’s most searing exploration of the human condition doesn’t even make the grade here while Hamlet only comes in at number 10, after Love’s Labour’s Lost and the two Henry IV plays, with Macbeth at 14. But then the author of this playful, as it were, collection repeatedly assures us that his rankings and choices are cheerfully subjective and reflect his own most cherished experiences of the theatre. Not since Kenneth Tynan, kingpin of British theatre reviewers (he is repeatedly evoked in the collection), has there been a drama critic as incisive as Billington.

To the extent that this book offers its readers 101 reviews of important plays it is a veritable treasure trove. Billington comes to the table with some 9,000 plays under his belt, his skills and talent honed over a period of 50 years of reviewing. There can be few better guides to the living theatre, to the glory of plays ancient and modern, than this anthology of critical essays about plays that have shaped the way we look at the world while entertaining us over the course of two or three hours. If readers want to know about Menaechmi (ranked 5 out of 101 here), the comedy by Plautus that provided the comic matrix for Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors, they might turn to any number of sources. But this one alone will give them, in four succinct pages, the gist not only of the play but of what makes it tick on the stage as drama, now as much as it did 2,000 years ago. Billington’s eye and ear for what works in the theatre are unerring. Every single discussion is a model answer on plays in the theatre and, often, informed by the latest scholarly debates on them, as is evident from, among others, his Shakespearian discussions. He is uniquely placed to tell us about the plays as theatre because he has seen every one of them done more than once on the stage. At times he emerges as the most-to-be-envied person in Britain, constantly at shows and able to learn from them.

As for the highlights of the selection, apart from a bunching of Shakespeares among the top 15 (they bag 30%), at number 1 and 2 are plays by Aeschylus and Sophocles, one not very well known, the other arguably the most influential play in the world, while the last two, 100 and 101, are works by Butterworth and Bartlett that the present reviewer had not heard of. It would be churlish to give away Billington’s ranking order and, in truth, that is not the book’s primary appeal. Rather it is the individual entries that so enrich it. Most readers and theatre audiences will have heard about the Golden Age of Spanish drama, but how many have caught performances of plays by Calderón or Lope de Vega? No fewer than three of their plays feature here and Billington’s richly suggestive discussions of them effortlessly draw us in their ambit. If the Spanish plays are not exactly household names in Britain, what of D. H, Lawrence’s The Daughter-in-Law (58)? As novelist, writer of short stories and even poet, Lawrence is a big name, but as playwright? And yet, by the time Sons and Lovers appeared Lawrence had written six plays. Many of the old warhorses figure here: plays by Brecht, Chekhov, Ibsen, Ionesco, Miller, Shakespeare, Williams, and of course great classics from France by Corneille, Moliere, and Racine. Nothing new in that but for each of them Billington is able to home in on its core dramatic appeal. To do that for Molière may be easy enough though how many critics other than Billington can comment with such mastery on the nuances of translations of him?

And if the divinely funny Molière might just get away with less than perfect translations (it so happens that there have been at least two masterly ones into English), how much more important is it to get the best translations for Racine and Corneille, not generally known for their sense of humour. The discussion of Racine’s Andromache, described brilliantly as an ‘intemperately exciting work’, is a model of lucid exposition of its structure. Here as elsewhere Billington is able to test the play’s drive by comparing different productions of it, in 1985 and 1988, and by referring to other plays that deal with the tragi-comedy of unrequited passion as in, for example, Chekhov’s Seagull.

Inevitably Chekhov looms large in this book – how could he not. The Cherry Orchard passes the Billington litmus test, if only at 53 when perhaps it should be up there among the top five in a league table of the greatest plays. It is, the author concedes, one of the unchallenged masterpieces of twentieth century drama; perhaps the most enthralling play altogether of that century. In the end, we are told, ‘the beauty of The Cherry Orchard lies in its openness, abundance, and multi-dimensionality’, to which one might add its largesse of spirit and countless subtle hints and twists inside a seemingly plotless play.

‘Open’, ‘abundant’, ‘multi-dimensional’ are all epithets that apply to this engrossing trawl through a wonderland of 101 great plays. And finally, yes, Billington is keenly aware of the absence of King Lear from his shortlist and he does explain why it didn’t make it into his subjective canon. For that matter, he might have needed to include most of Shakespeare’s plays, Chekhov’s, and Ibsen’s, which would have severely curtailed the scope of his book. As it is his long shortlist is supplemented with contextualizing references to many other plays that are not specifically included but which are used to underpin the discussions of the ones that are. Enjoy.