First produced at London’s Bush Theater in 1993, Helen Edmundson’s The Clearing is about Oliver Cromwell’s horrific policy of ejecting the Irish from Ireland, set in County Kildare in 1652. In Theater 808’s production, director Pamela Moller Kareman sets the play “over the course of three years” without specifying the year. This is our first hint of Kareman’s concept for the play. Further clues are given with Jason Bolen’s abstract set – 6” gray platforms with obvious gaps between them, gray cubes scattered stage right, wooden posts with metal wrappings that suggest a wooded area and a beautifully constructed and easily scaled wooden panel that curves up several feet.

Then there are the costumes. Kimberly Matela’s designs are contemporary – hoodies for both the peasant and the British landowner, slacks for both sexes, business suits for the villain.

It is only as we view the play that we begin to understand the meaning behind these abstract and contemporizing clues. We are meant to apply metaphoric thinking to make the shock of those historical events relevant to our times. The gaps in the platforms mean that the actors/characters must tread carefully or risk breaking an ankle. They will be metaphorically maimed by their very attempt to exist in this world of precarious loyalties.

The story of The Clearing is one of marital strife incited by national politics and by the depraved morality of the occupying British in 17th century Ireland, transplanting the Irish to Connaught, the colonies, or the gallows. Loyalties to country and marriage vows are at stake.

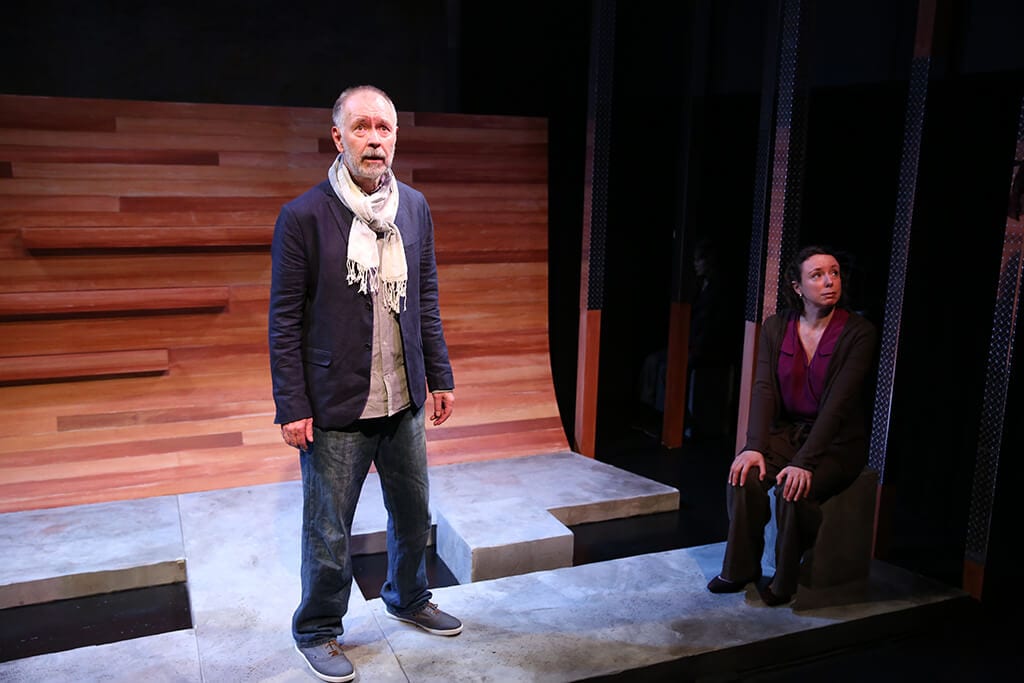

Edmundson’s story funnels this national tragedy into a personal one involving the marriage of Robert Preston, played by Jakob von Eichel with a British stiffness not only of his upper lip but of all his limbs. At the opening, he is the proud father of a son apparently madly in love with his wife (a vibrant Quinn Cassavale). She appears with their baby boy, miraculously recovered from a difficult labor. She is meant to be the most sympathetic of characters – passionate, free-spirited, almost reckless in her Irish indignation, while her husband is self-serving and ultimately weak, abandoning his wife for political safety and survival.

Cromwell’s policy affects the lives of everyone around the Prestons, even ironically of other British settlers. Their good British neighbors, Solomon and Susanna Winter (David Licht and Tessa Zugmeyer) settled in Ireland 30 years prior, but they too will be transplanted as their former loyalties are now treasonous. Preston and Solomon appeal to Sir Charles Sturman (Neal Mayer), a thoroughly inhumane and despicable character. But to no avail. Mr. Mayer gives us little room for much understanding of his character other than his vengeful motive. In all fairness to Edmundson, the brutality of the English at this time was so severe that she probably didn’t feel disposed to deepen this particular character.

Still, we feel glimpses of profound despair such as when Madeleine Preston finds that her dear friend, Killaine Farrell (Lauren Currie Lewis), has been raped and is about to be sent to Barbados. Ms. Lewis’ performance throughout of this gentle and simple girl has touched us, but never so much as when she relates the crimes against her and thereby her country.

This is a laudable endeavor to make this dark period of Ireland relevant to a 21st century audience. By modernizing the look of the play, attempting to tie it to contemporary issues such as ethnic cleansing or the Holocaust, it creates an emotional distance, becomes more intellectual. Ultimately and ironically, we are less moved by the Irish reality of 1652.