The Magic Flute returns to the English National Opera this week to much applause. The revival of the dircetor Simon McBurney’s 2016 production brings back a crowd-pleasing show that is chock-full of magic, mythology, and love.

We meet Tamino, a young prince being chased by a giant snake through a rocky wilderness. We do not know who he is, where he is, or how he got there – but it soon none of that matters. After Tamino faints from fright, he wakes up to find himself in a mythical world that proves infinitely as complex to navigate as the forgotten reality from whence he came. Rupert Charlesworth as Tamino has a strong voice, well matching the princely valor that both the Queen of the Night and Sarastro recognize in him.

The Queen of the Night (Julia Bauer), ruler of the rocky wilderness, hears of the young prince in her lands and sends her handmaids after him. After waking from his faint, Tamino is recruited by the Queen of the Night to rescue her daughter, the princess Pamina, who has been kidnapped by their enemies. Tamino, of course, has fallen in love with her lovely visage the moment he set eyes on her picture. So Tamino sets off to rescue the princess. In tow is the reluctant, constantly chattering – and often scene-stealing – Papageno (Thomas Olimans), a man who makes his living selling birds to the Queen and dreams of finding a love of his own. But what the two men discover on their quest is not what they had expected to find.

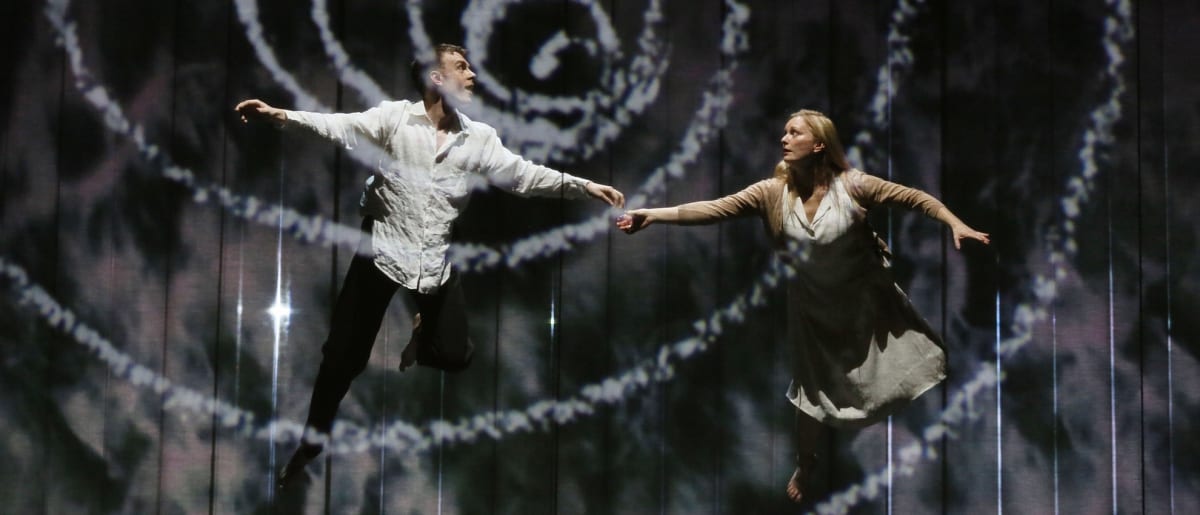

And so an epic battle between light and dark is revealed. Our heroes are thrown headlong into the action, forced to fight their way back to one another as much as they must resist the evil forces around them. Lucy Crowe as the princess Pamina depicts a soft, kindly woman, but one who is fierce in the face of adversity. She sings with a clear, strong voice, the very cadence of which leaves no doubt as to her goodness. Her scenes often brought the most enthusiastic applause. Pamina’s mother, the Queen of the Night (Julia Bauer), offers a competent but slightly underwhelming performance. However, her character is interestingly complicated by director McBurney’s choice to have her dependent on a wheelchair. The Queen seems to be able to get by without it in Act I, but her dependence on it grows as she loses her controlling grip on Pamina and Tamino. By the time of her final appearance in Act II, she cannot walk at all. For me, this makes her all the more pitiable. Her disability is the only thing that she is not lying about to Tamino or Sarastro, and it explains why she must trust her evil missions to her daughter and the prince. Her failing physical abilities mirror her waning power, and the wheelchair is a tangible reminder of how desperate this queen has become.

But the star of the show was the ingenious chalkboard writing. Controlled by a man sitting on stage and projected on screens over the action of the opera, the chalkboard writings – whether used to introduce the characters, or to suggest impossible special effects like the giant snake or a whirlpool – are a fun and unique way of modernizing the story without interfering with the archetypal fairytale feel of the opera. The chalkboard, which has the feel of a Hand of God, also adds to the prevailing sense of magic and myth in the world laid out before us. And from the beginning to the very end, the chalkboard gives the opera the sense of a child’s book of stories, which closes quite neatly only after the Happily Ever After has been achieved. In this way, The Magic Flute will leave you happily satisfied, and dreaming of magic.