The Suicide takes Nikolai Erdman’s satire and thrusts it, wholesale, into the world of 21st Century London. It follows Sam Desai (Javone Prince), unemployed and desperate, whose suicide threats are captured by local teen Gil (Michael Karim) and quickly become a viral YouTube sensation, bringing swarms of media and pseudo-activists to his estate. The Suicide is billed as a comedy, and in that it mostly succeeds: the first twenty minutes left much of the audience in stitches, and some brilliant individual vignettes (particularly an acid-tongued jab at This Morning) meant that there were laughs throughout.

However, the central joke of the play – the satiric look at our slactivist, hashtag tragedy culture – starts to wear thin long before the second half, and is largely kept alive by vibrant performances from Ashley McGuire (who plays mother-in-law Sarah) and Paul Kaye (“activist and filmmaker” Patrick). The moments of real tragedy, of real fear and anger, are quickly subsumed by the farcical – the occasional genuinely shocking moments are not allowed to fully exist before we are swept along by something else. This could well be a deliberate comment on the fast-moving nature of internet activism, on how quickly popular sympathies move onto the next target, but if so, it sacrifices real investment in the central characters for ineffective social commentary. In the chaotic final scenes, Sam’s speech – which had the potential to be one of most moving sections of The Suicide – is not allowed to finish, but is swept away by the gaggle of hangers-on.

The Suicide is a piece that feels almost overwhelmingly self-aware of its own would-be subversiveness, but there are moments where its brand of satire works. Its frank look at the political games played with mental health provision, and a particularly surrealist scene where Thatcher stalks the privatised afterlife, are effective, the darkness allowed to linger for a moment. When slam poet Igor (Tom Robertson) wanders on, dressed like a mixture between Macklemore and Kanye, the audience erupts into laughter, because it feels true. Unfortunately, there are few moments where its wry nods to popular culture connect so absolutely. The Suicide presents a hyperbolic, amped-up version of 21st Century life, and sometimes it gets so caught up in the larger-than-life archetypes of its characters that it feels like it has lost its grip on the poverty and frustration that define the early scenes.

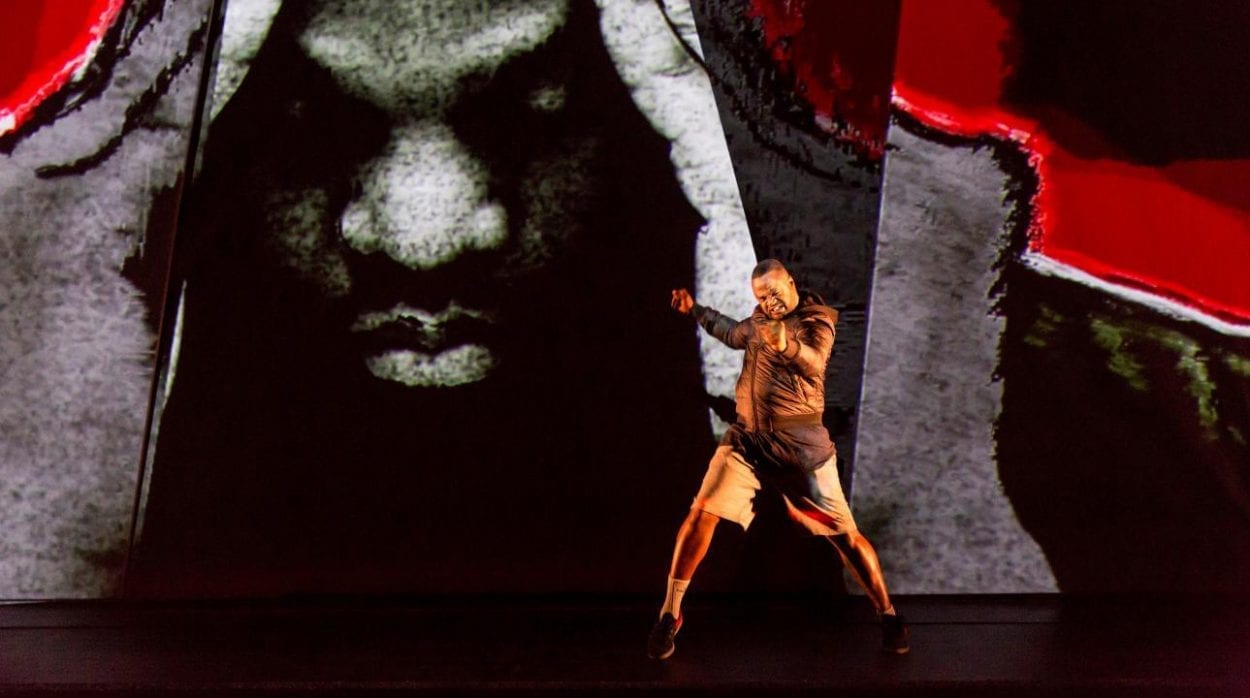

The production is saved largely by its director, Nadia Fall, whose vision of a multimedia world provides some of the best moments of the play. The throbbing, multi-layered set, full of fragmented block shapes, provides a greater sense of depth, and of the fast-paced London environment, than anything in the script. Opening credits, songify remixes of Sam’s speeches and cartoon graphics all add a sense of the layers of media through which we all live our lives, a building pressure that is, ultimately, frustrated by the script.

The Suicide is not the failure that many critics have branded it as, but nor does it live up to its early potential. The lack of compassion shown by its ensemble characters does not leave us feeling angry, but cold. The twists can feel somewhat predictable, but that would not matter so much if we were more caught up in the story. Prince does his best with Sam’s outbursts, but he is never allowed to properly get going. The Suicide is undoubtedly funny, undoubtedly accessible, but, this time, that is not quite enough.