In 1972 actress Jane Fonda travelled to North Vietnam as part of her on-going mission to halt what she perceived to be America’s futile, destructive and unnecessary involvement in the Vietnam War. She was photographed laughing with the North Vietnamese people who America was fighting, talking to American soldiers who were prisoners of war and happily sitting astride an anti-aircraft gun that’s purpose was to shoot down American planes. She gained the nickname ‘Hanoi Jane’ and became a figure of hatred for many patriotic Americans and was labelled a traitor. In 1988 shooting of a film starring Jane and Robert De Niro was halted when war veterans held demonstrations. Terry Jastrow’s play, starring his wife Oscar nominated Anne Archer, imagines the real life course of events as they might have been when Jane decided to hold a meeting with the angry mob of men.

Jastrow talks about using a triangular technique when he researched the events preceding and during this tense encounter between a formerly strident protester and the people who felt personally slighted by her actions and labelled her a seditious Communist. His technique was to scrutinise events through the eyes of at least three eye witnesses. His research was extensive and involved travelling to Hanoi, staying in the same hotel as Fonda did, as well as spending time with the veterans and with Fonda herself. His story is meticulously written, heavy with detail and timely with resonance given recent revelations surrounding the Gulf war.

It’s a fascinating story and one worth learning about even if just for for its parallels. The script, whilst lacking dramatic tension at times, is dense and interesting to watch. Archer is masterful as a steely Fonda with hints of compassion that is ready to surface when needed. The main problem is that it all feels slightly one sided. Fonda is serene, reasoned and composed. She’s barely ruffled at all by this violent outpouring of hatred and resentment. By the end of the play she seems only mildly dented by the encounter and has had little cause to waiver in her reflection on past events. The veterans seem unreasonable, bitter and mostly unshakeable in their resolve. Whilst there are nods to their pasts reflected through their stories of the conflict and the acting is universally strong, they seem lacking in flesh. It feels like a court case that we always knew the outcome of and one which was too easily won.

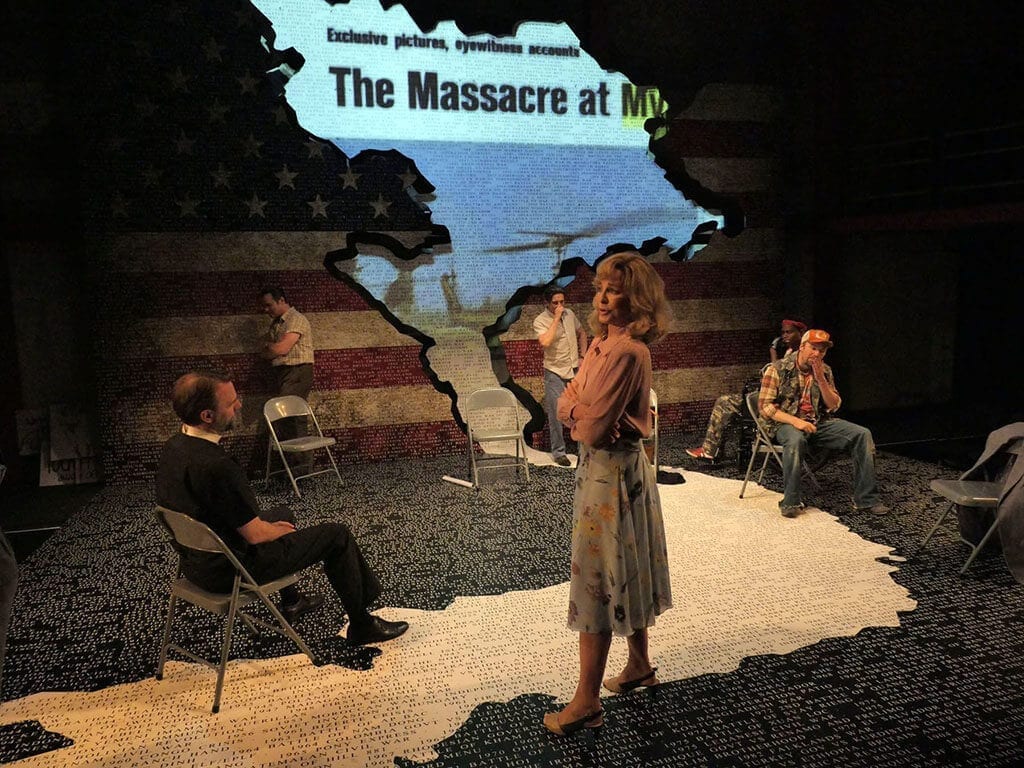

The set by Sean Cavanagh cleverly features a wall covered in the names of twentieth Century battles and is a huge American flag split in two by a map of Vietnam that doubles as a projection screen. The video clips work well to add context. Adding to the atmosphere is the slow rumble of Matthew Bugg’s moody soundtrack.

It’s a worthy play and is no easy ride to watch but has rewarding elements. It would have been nice to see more of a battle and more evidence of the triangulation of accounts that Terry Jastrow talks about.