Shakespeare is the world’s global literary brand, as popular in Africa, America, and Asia as he is in Europe. For the last 30 years Shakespeare’s internationalism has been growing exponentially to the point where, at this very moment, the Globe Theatre in London is taking Hamlet on an epic tour of the world, aiming to perform the play in every single country on earth. In Andrew Dickson global Shakespeare has found a talented champion. This is as brilliant a book as it is generous and inclusive. Over 400 pages Dickson records the results of nearly four years of globetrotting in the imaginative footsteps of the poet dramatist from Stratford-upon-Avon. His journey takes him from Germany to America, India, South Africa and finally to ‘the middle kingdom’, China, the new power house of the world which has discovered Shakespeare in the course of the last 20 years and is tackling him with the most extraordinary zest.

By starting in Germany and particularly with Hamlet, Dickson acknowledges that the cradle of Shakespeare studies was ultimately the country of Goethe and Schiller; or perhaps, less grandly, of Schlegel and Tieck whose seminal translations of Shakespeare into German set the points for a Europe-wide bardolatry that matched anything in post-Garrick Britain. They also inspired Coleridge whose critical thinking about Shakespeare was profoundly influenced by the Germans. Paradoxically it may be the distance from the hypnotic power of Shakespeare’s language that, according to Dickson, eases non-native speakers into the magic of Shakespeare. In translation Shakespeare inevitably sounds modern to the ears of the target audiences while Early Modern English to us is just that; and, as Dickson reminds us, it is quaint-sounding to our ears if spoken in the pronunciation of the time and, with its post-vocalic ‘r’ markers, seems irksomely closer to American English than modern British RP.

Any in depth discussion of Shakespeare in Germany inevitably sooner or later touches on the way plays such as The Merchant of Venice were interpreted in the theatres of the Third Reich. Dickson is acutely alert to the dilemmas posed by the plays and their interpreters during the years of tyranny when Shakespeare was both an enemy nation’s core writer while also being claimed by the Germans, historically and long before the advent of the Nazis, as one of their own. He refuses to indulge in clichés when discussing Shakespeare during the long European night, aware of the fact that the plays were in turn written during the most sectarian period in English history, a history that is itself reflected in plays like King Lear and Macbeth and in the martial play that lends its title to this book, Coriolanus. The climate of violence and hatred in the 1930s may chime more with the original period of the plays than with anything since in Europe.

‘The roads up into the Sierras were twisting rat’s tails, winding and jackknifing’, Dickson writes as he is driving (even ‘barrelling’) in search of the town of ‘Rough and Ready’ in California. Once upon a time there had been a small theatre here embedded in a hotel and Dickson is hoping to find it. His southern California pages could have been written by Chandler, for the way he evokes settings which are after all inextricably linked to his subject matter. Style may be this book’s most distinctive feature, the fact that the search for the common good of Shakespeare across continents is conveyed in a language that never ceases to dazzle and seduce. This could easily have become a worthy scholarly, dull tome. Instead it is quicksilver lively and full of colour while relishing the otherness of those worlds elsewhere that have tried to make Shakespeare their own. When our narrator strays (actually, trespasses) into the grounds of a superstar actress in India, we are there with him, just as we accompany him on his many train journeys and flights. By his joyous courting of the English language Dickson at times brings to mind the young Patrick Leigh-Fermor.

The Robben Island Shakespeare has become something of a holy grail in Shakespeare folklore, a copy of the mass-produced Alexander Shakespeare that for years was a standard text for years in British universities. It was smuggled onto the prison island by the wife of one of the ANC inmates. They all read and annotated it, if only by marking and signing their favourite passages. Since the collapse of the apartheid regime this humblest, most austere of Complete Shakespeare editions has in turn toured the world. When in 1599 Shakespeare made Julius Caesar proclaim defiantly that ‘Cowards die many times before their deaths. / The valiant never taste of death but once’ he never imagined that some 380 years later the world’s most famous prisoner would in turn defiantly pick those lines as his favourite among Shakespeare’s. The Robben Island Shakespeare is discussed here in situ, not without a certain frisson as Dickson traces the history of responses to Shakespeare in this most complex moment in history, when the inner strength and stoicism of a handful of men in the end triumphed by passive resistance over an oppressive regime.

The link between South Africa and India in this respect is intimate, and tangible historically in the person of Ghandi. If Mumbai appeared to Dickson to be a Shakespeare-free zone, in Kolkata Shakespeare ‘seemed – like the British – to be everywhere’. Familiar names like the Kendals, the parents of, among others, the British actress Felicity Kendal, surface in the context of the 1965 Merchant Ivory classic film, Shakespeare Wallah, and launch us into a fascinating discussion of the evolving relationship of India with the former imperial power’s favourite author. At some point Dickson finds himself momentarily adrift at a conference in Delhi: ‘I was finding it difficult to join the dots. So many theories about Shakespeare, about India, about Germany and the US, so many cultures, interpretations, languages … Mumbai and Kolkata had left my head in even more of a scramble than usual. All these different adaptations … It felt as though one could go on for ever, and never reach the end’. He was sharing his moments of doubt with a professor, a specialist ‘on Hindi cinema, who was also bunking off class. The Indian professor replied: ‘‘Old chap’, he said softly, ‘isn’t that rather the point?’’ Quite so.

The book is studded with gems like this one, combining a remarkable inwardness with the minutiae of Shakespeare’ plays with a revealing series of cross-cultural dialogues. Dickson not only knows the plays and myriad adaptations of them, but he is able to hear what others have to say about Shakespeare. He is as conversant with the inner sanctum of the Folger Library in Washington as he is with a forlorn corner of southern California where once long ago there stood a ramshackle, makeshift Gold Rush playhouse. His book time and again surprises even seasoned writers with nuggets of information as, for example, when he discusses translating Shakespeare into Mandarin, where ‘Romeo’ becomes ‘Luomiou’ and Rosaline ‘Luoselin’; not to mention the challenges posed by ‘To be or not to be’, since Mandarin cannot render the conceptual duality of English ‘be’, meaning both to exist and, as Dickson puts it, possessing ‘the much broader ontological sense’ of being.

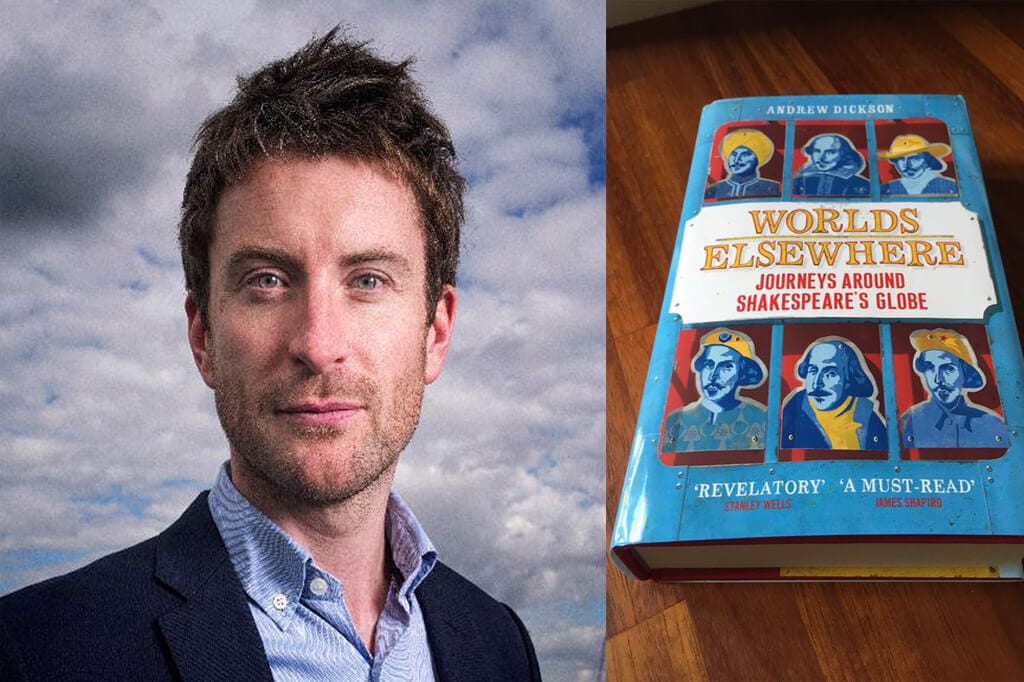

Ever since his tour de force Rough Guide to Shakespeare Andrew Dickson has been among the most exciting young writers on Shakespeare, perhaps the most gifted of all. In every respect Worlds Elsewhere is an exciting match for its maverick predecessor.

By Andrew Dickson

Publisher: Bodley Head (15 Oct. 2015)

ISBN-13: 978-1847922458