Woyzeck in Winter fuses Franz Schubert’s Winterreise with Georg Buchner’s unfinished masterpiece Woyzeck. It’s an odd idea. The two are united by the fact that their makers were both German, were born within a couple of decades of each other, and both died whilst trying to complete the works in question. Which perhaps makes the idea of throwing them together marketable. But in truth these two men were worlds apart. Schubert exemplifies German Romanticism, whilst Buchner is widely considered a proto-modernist. Schubert’s song-cycle is lyrical and melodic: its constituent parts united in the objective of conveying a mood or emotion (typically melancholic). Buchner’s play is fragmented, dissonant and schizophrenic. Putting the two together is like scoring a David Lynch film with music by the Eagles – for the reason that they’re both American and (though in wildly different ways) sometimes a bit sad.

Conall Morrison’s production is baffling. I’m not sure I’ve never seen so large scale a production with so little attention paid to detail. Marie and Woyzeck’s child is a Baby All Gone. The Showman wears a full body tattoo shirt of the kind that someone directing a primary school production might reject for over-exposing the limitations of the budget. Maybe this sounds like I’m being fussy. But there’s so much inattentiveness that it’s hard not to spend most of the production being distracted by it, and wondering whether it’s intentional – like some big, bizarre postmodern experiment.

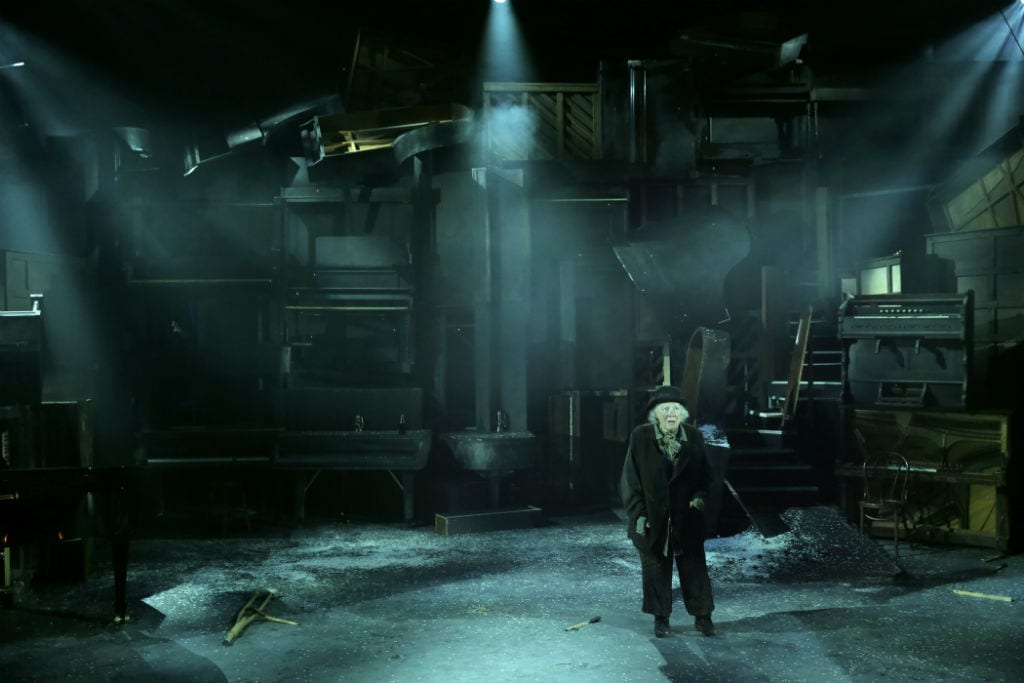

More troubling than these cosmetic issues, however – is the difficulty in discerning why this play had been chosen. The sexual politics of Woyzeck are fraught: on the surface it’s a deeply offensive play about a man who murders his sex-craved wife for having cheated on him. It’s only redeemed if we as an audience are encouraged to understand why exactly it is that Woyzeck should illicit our sympathies: in particular, the way in which his behaviour is a product of the dehumanising influences surrounding him. Conall Morrison’s production sadly fails to interrogate these possibilities in a way that is in any way elucidating. On the contrary: the story of Woyzeck seems to be romanticised. The whole feel of this production, and its set made out of wooden piano frames – suggests that Buchner’s play has been read uncomplicatedly as a gripping yarn.

In spite of these shortcomings, there are some powerful performances in this production. Patrick O’Kane (as Woyzeck) is strong – though he comes in with such a full force of energy that he gives himself nowhere to go. And Camille O’Sullivan can be beguiling as Marie, though her performance sometimes veers into melodrama. My favourite performance was Rosaleen Linehan as the Hudy Gurdy Man: understated and uncanny.