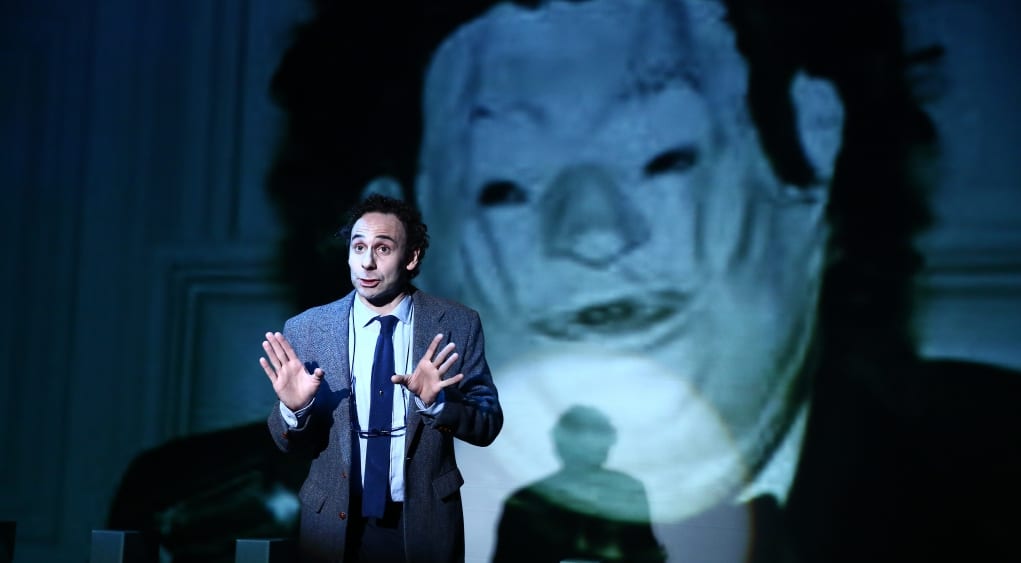

In 1972, Dr. John Fryer put on a rubber joke mask, a voice modulator, and the name Dr. Henry Anonymous and spoke as the sole psychiatric representation to the members of the the American Psychiatric Association on behalf of homosexuals, to make a stand against the diagnosis which labeled them as deviant and mentally ill. A year later, this momentous speech would bear fruit as the APA officially repealed its diagnosis. This year marks the 45th anniversary of this repeal and the month of the annual APA conference. To commemorate this momentous step in LGBT activism, Equality Forum brings 217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous to the New York stage for the first time. 217 Boxes of Dr. Henry Anonymous explores the man behind the mask through the people behind the man: an aging pre-revolution gay activist Alfred Gross (Derek Lucci), Fryer’s elderly secretary, non-wife, mother-figure, and friend Katherine Luder (Laura Esterman), and his reticent southern father Ercel Fryer (Ken Marks). Though they are hidden from history, they played an integral role in shaping this ordinary man and his path to doing an extraordinary thing. In separate monologues, each one meanders his or her way through the 217 boxes left over from Fryer, including patient records and family letters. These boxes hold the story of these forgotten figures.

What first hit me when entering the Baryshnikov Arts Center was the stage design: rows upon rows of gray boxes which increased in height as they went upstage, creating a practical replica of the Jewish Holocaust Monument in Berlin. While nothing in the play or the talkback made any mention of this architectural inspiration, it struck me hard. Here, as an unnamed setting for a contemporary LGBT play, is a connection between two horrific examples of prejudice of the 20th century through the anonymity of oppression’s victims. In this setting it becomes a monument for those who remain anonymous within the disease that took their lives, those that had to either disguise or assert but could never just be. These are the stories told masterfully through our three performers.

Lucci, Esterman, and Marks all take the audience on individual journeys of their own lives and their connection to our titular doctor. Archetypes are played with, stereotypes are acknowledged and spelled out, diseases looked at from perspectives rarely explored, and love is shown even when fear and discomfort is present. Humor, heartbreak, and revolution are the through lines of all three tales, though in different, illuminating ways. There is the aging, unmarried, working woman who finds herself having to learn new words and new worlds and the wonderful opportunity to see the AIDS crisis from someone just on the periphery, who must choose between protecting herself from the unknown and standing by those who suffer. One of the most beautiful moments of the entire show sees Esterman standing still, naming box numbers instead of the lost she can’t name. She never speaks the words or names the name, but the audience knows what she speaks of and mourns with her. Alfred Gross is the man before, the one who started picking the battles before those we acknowledge as the ‘firsts’, those who we today perhaps blame for stopping too short. And finally, there is Fryer’s father, a man who chooses to reveal as much as he can in as little words as possible because it was all he was taught to do. He exposes a parent’s fear when his love for his child must face off against long held beliefs. Undeniably moving, 217 Boxes is a revelation, a turning point in LGBT history told through the voices lost to boxes and archives.