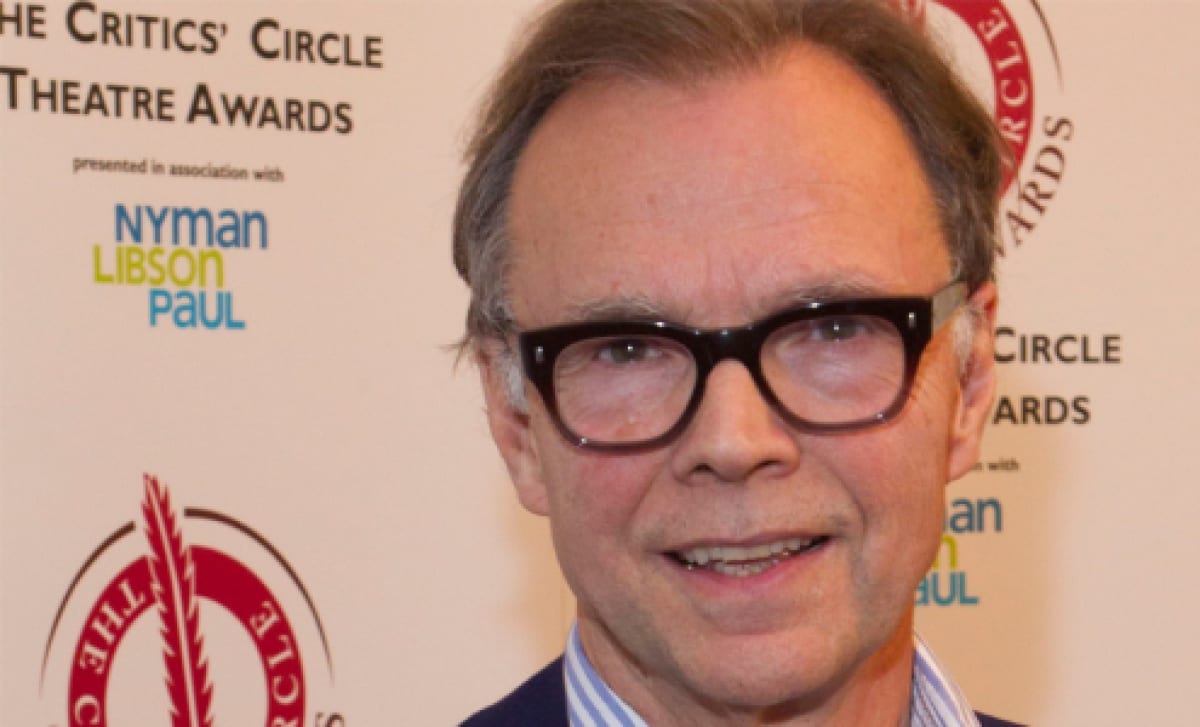

Jonathan Kent in conversation with Rivka Jacobson

He is a director extraordinaire, seeking to challenge the audience with productions of hardly ever-performed plays to a popular and often performed opera and plays. His recent production of Christopher Hampton’s play A German Life, casting the legendary Maggie Smith in a solo performance, was sell out as are most of the productions directed by him.

The forthcoming revival of Tosca at the Royal Opera House, with its stellar cast and the limited number of largely sold-out performances, is one of the hottest tickets in London this summer. Then, later in June, a much-anticipated, radical version of Peer Gynt, adapted by David Hare and billed as Peter Gynt, will be staged at the National Theatre. Both productions are directed by Jonathan Kent and will showcase his versatility as a director of opera and theatre.

We spoke late last year, when the new play by Florian Zeller, The Height of the Storm, which Kent directed, was in the midst of its two-month run at the Wyndham’s Theatre. We met at his flat in London.

Kent is relaxed and down-to-earth: an English gentleman with warmth. He grew up in South Africa but matured in the UK. From 1990 until 2002, he and actor Ian McDiarmid were the joint artistic directors of the Almeida theatre and were largely responsible for transforming it into a powerhouse of successful productions. During their tenure, the Almeida featured a wide range of international plays – from Ibsen and Chekhov to Racine and Molière – many of which transferred to the West End and Broadway. In February 2016, Kent was appointed Commander of the British Empire (CBE) by the Queen for his services to the performing arts.

Rivka Jacobson: Your formative years, age one to 19, were spent in South Africa. Would you say your upbringing in that country affected the way you perceive and think about your work?

Jonathan Kent: To a degree, in that, although I sound more English than the English, I’m actually not. My formative years were in South Africa, and I think the light that is burnt on your retina when you are three years old is what forms you. And although I work very happily here in England, it is always at a slight angle, because I am not through and through English. I grew up in Cape Town, which is an extraordinarily beautiful place – and I think beauty is a sort of moral force. I admire beauty. It was great to be surrounded by beauty all of my childhood, so I suppose that has formed me. So South Africa is imprinted in me. I don’t know whether it has a very specific influence on my work. I don’t think so particularly, but it does mean that I am at one remove from the culture I operate in.

Kent began his professional career as an actor in Glasgow. He recognises that “a lot of what I believe about theatre was formed in the seventies in Scotland, which in those days was an astonishing anomaly. It was a baroque theatre when the prevailing fashion was modernism and aestheticism. In Glasgow, there was a very florid, baroque approach to theatre. And we did a lot of European theatres and toured Europe. That was very formative.” He recalls that after two years, “the extraordinary Phillip Prowse the designer and the director, was the first person that said to me that I should direct. He heard me bossing people around!” Kent adds with a smile.

Kent admits that he did not really enjoy acting: he did not like 800 people staring at him each night: “What most actors like is the anonymity of the crowd, but it made me uneasy.”

The transition from being an actor to a director seemed natural to Kent: “It’s interesting that when I started directing, I remember thinking on the second day – I don’t care what anybody else thinks, this is what I should be doing.”

His excellent spatial awareness may be ascribed to the fact that he comes from a family of architects: “I always imagine a production as building a house.”

His twelve years at the helm of the Almeida with Ian McDermid propelled his career to new heights. Reflecting on those years (1990-2002), Kent reminisces: “It was astonishingly successful given its humble beginnings, and actually that was great protection because we had no conception of how difficult it should have been. We raised the money ourselves and ran our productions and they became very successful and we ran theatres in the West End, transferred to Broadway and we built two temporary theatres. Now I look back with astonishment!”

As to the best shows of those years, Kent says: “There were many actually, and not always the most successful ones. But the one that had the most emotional undercurrent was our final production at the Almeida. Only Ian and I knew we were leaving, and we did a production of The Tempest. It was in the ruins of the old Almeida: the roof was coming off, we flooded the basement and put the stage in there. Ian played Prospero and I directed it, it was our farewell to art, much like the play itself. So that had a huge resonance for me. But the productions there that I value were the productions that started alliances and friendships, like with David Hare, Ralph Fiennes and so many actors and writers. We have built up a body of work together.”

The repertoire Kent flirts with is broad and varied. He tries to get British writers to translate plays written in foreign languages. As a result, great European playwrights find new expression through contemporary British writers. His forthcoming production at the National Theatre of Peter Gynt adapted by David Hare is a case in point.

RJ: Does the translator have as much input into the dialogue as the original writer?

JK: Sort of. I think there is no such thing as a pure translation, it’s always a version. Just taking the example of Peter Gynt, what we’re talking about is ‘Peter Gynt, by David Hare, after…’. It’s taking the play and being entirely true to the spirit of the original but tampering with the lettering. I’ve done that quite often. David and I did three Chekhov plays at the National. Platonov is very incomplete – it’s a series of notes and seeds that if you performed in its entirety would take six hours. But David collated it into a very successful play. It was very much David Hare rather than pure Anton Chekhov.

RJ: Do you think the director gives the play a new life? Chekhov can be terribly dull if it isn’t properly directed.

JK: You must tap into the energy of the original, which doesn’t mean frenetic action. Any revival, whether it be 19th century or Shakespeare, is a conversation between the time and place the play was originally written in, and the time and place it is being done in now. It is a conversation between those two poles.

RJ: And you as the director try and bring it into the 21st century?

JK: We don’t have to do it all in shell suits, but it has to be completely accessible to a contemporary audience. It has to have immediacy, and sometimes, as all great universal theatre does, it has to reflect our own times as much as it reflects its own.

RJ: Do your political views inform your plays?

JK: Sometimes, absolutely. But what you have to try and do is be true to what you divine is the original. By divining what you think is the true essence of the play, inevitably you bring your own sensibility into it. Inevitably my views and philosophy of living are reflected in the plays I choose to do, and how to do them.

RJ: Do you choose which plays to direct?

JK: Sometimes I’m asked. But I choose whether I do them or not. That’s a standpoint on its own, whether or not you elect to do something.

RJ: You recently directed Florian Zeller’s The Height of the Storm. The production was a success, although the subject is rather challenging and somewhat morbid. What was the attraction?

JK: Zeller has two plays, The Father and The Height of the Storm, which are only partly about people at the end of their lives. I think it’s astonishing that a man who is 38 is so acute about ageing. It’s remarkable. But what I like about The Height of the Storm, is that it’s about love. And actually, it doesn’t matter that the protagonists are old. It’s about the enduring nature of love, which doesn’t depend upon the object of your love is being in the room, or alive even. Love is something that is constant in the lover. It is universal.

RJ: Did you have any concerns about the audience it might draw?

JK: I was worried it would only be for old people, but actually everyone has been affected by these issues. Whether it’s your grandparents or parents, everyone has been brushed by mortality and the collateral damage of that.

RJ: Did you have any preconceived ideas about how you wanted it staged?

JK: I knew that it resided in light. I knew that because the ‘realities’ are shifting realities. On the page it is quite flat, so on stage, you have to manipulate light across the characters so that sometimes they retreat into limbo, though still on stage, but not have the same presence as other people. I knew that it would be important for the audience to know vaguely what is going on, although it is still mysterious. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with mystery in theatre. But I knew that we had to tell the story with light.

RJ: How complex is the process of casting the right actor?

JK: It’s part of the process, and it’s almost the most important thing a director does. Being a director is sort of being like being the editor of a newspaper. You choose your columnists and that is a vital decision to make. You imagine what the actor or actress will bring to the part, and then you let them fill the role. In this production, anyone who is interested in theatre should see Jonathan Pryce and Eileen Atkins. They are a masterclass in live acting.

RJ: Have you ever realised in rehearsals that an actor you have cast just hasn’t quite got it?

JK: Once or twice. And it’s not about whether they are good or bad actors, sometimes the chemistry of the actor and the part don’t quite fuse.

RJ: Music can be crucial in creating the atmosphere in a play. How do you choose the right music?

JK: Well, that’s the funny thing about The Height of the Storm. I always thought I wanted to use Sibelius, and right up until the tech, I was trying to put Sibelius in. But it is theatrically inert. It’s the most glorious piece of music, but theatre music is meant to advance the narrative, not stop it. Sibelius deadened the play. Gary Yershon is a composer whom I have immense gratitude for, and thankfully he came in and in 24 hours composed something that did exactly what I’d hoped it would. It was wonderful. I’ve also done musicals and opera, so I love working in music. I’m about to do this huge production of Peter Gynt and music is so critical to that. It is clad in music. I’m starting to work with a composer this week. But that is, just as much as the design, a critical part of the presentation of a piece. Peer Gynt has the awful precedent of Grieg, but this music is very different.

Kent has also directed opera. The challenge he has with directing opera is not what we might think. Kent explains that the problem with opera, “as much as I admire it and love doing it, you are booked three or four years in advance. Theatre operates on a much shorter timescale, which meant I had to turn down projects I really liked just because I’d booked on to an opera a year earlier. I just felt that I was disappearing into opera, and much as I love opera, my primary pursuit is theatre. But it doesn’t mean that I don’t want to do opera, just that I want to control it.”

RJ: Why do they ask so far in advance?

JK: It’s just the way. I had agreed to do an opera in America next year, but Peter Gynt appeared. They were very understanding and great, but I don’t like doing that.

RJ: How does directing an opera differ from directing a play?

JK: Part of the task of doing a play is finding the inner rhythm of the piece, it’s like music but with text. In opera, the music is already there, it just needs to be coloured in. They aren’t that different; it’s all about telling the truth of the story.

RJ: You directed Tosca.

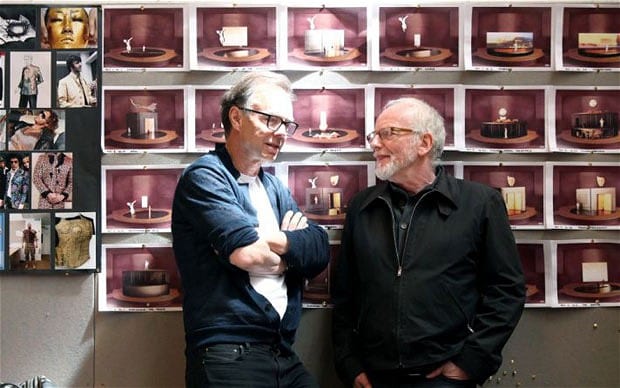

JK: Tosca is a cornerstone. When I agreed to do it, they said they wanted a production which they could revive. So, it’s a fairly classical production, it wasn’t particularly radical. But the brief was to create a production into which many different singers could go as it’s revived almost every year. You can’t be too extreme. That’s the difficulty of opera for me. If I had directed it in Mussolini’s Italy, it would have a more limited stage life than a very classical straightforward production. It was historically exact, which I had never done before, but I enjoyed.

RJ: What is your input as a director, if you have taken the libretto and the music exactly as they are?

JK: Tosca is a story of three people trapped in a space together. I had an extraordinary cast – Angela Gheorghiu, Bryn Terfel and Marcelo Alvarez – so, it was very much fashioned on them. Which has its own hurdles, because ten years later someone else is throwing on their costume. One of my small frustrations with opera is that a production has to survive lots of incarnations. That’s not what my instinct is. As a theatre director, my instinct is to fashion it on the people I see in front of me, and it becomes unique and specific to them.

RJ: In opera, I would have thought that when a person like Gheorghiu comes along, you can’t tell them what to do!

JK: Well she’d never sung it before, so you could to a degree. What you do is try and fashion and shape what she is doing.

RJ: Do they listen?

JK: Yes, they do. Bryn Terfel particularly is wonderful.

RJ: Many opera singers are terrible actors.

JK: Yes. But most are better than one thinks. There was an opera singer I thought was just terrible on stage. The most wooden and arrogant performer. However, when he sang out on the first night, his voice had such a soul. There was the trick of the light, the sound – to my fury, it was completely moving and compelling. Spiritual he wasn’t, but his voice had a soul. It was a lesson but also frustration. The voice had to do the acting.

RJ: Which opera have you enjoyed directing the most?

JK: I did a production of Purcell’s The Fairy Queen and what I loved about it was that it was a mixture of singers, actors and dancers – it was big. We took it to Paris and New York – it was a great celebratory piece. It was Purcell and the Restoration version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It was wonderful to have the singers, dancers, and actors overlapping – they all blurred into one great performance. And they all loved it too. I look back on that with huge affection.

RJ: Director and choreographer: is it a battle of egos or ideas?

JK: No. You tell the choreographer your vision and guide the process. I’ve done musicals, and there you work with the choreographer. In the end, you edit it.

Kent finds directing drama as challenging as directing musicals: “I think what amazes me about people who work in musicals is how hard they work but how little they complain. It’s demanding.”

RJ: Can you read music?

JK: Not really. I just follow it with my finger.

RJ: Your debut production at the Almeida was with Ibsen’s challenging, to put it mildly, play When We Dead Awaken. Were you over ambitious?

JK: I always say, when anyone writes to me for advice, whatever you do, don’t start with that! It’s a play I love. It’s Ibsen’s Tempest. But it’s hard work. One day I’d love to do it again!

RJ: You also directed King Lear. Do you like examining life from the perspective of old age?

JK: I suppose. My grandmother developed Alzheimer’s. I set Lear in a panelled room. My image for the play was rain falling through a panelled roof onto a sofa, that was the picture in my mind. And actually, looking back, I think it was quite a good production. But it was very much for my grandmother.

RJ: Is that why you chose The Height of the Storm?

JK: No, I was asked to do that. I was interested in the subject, but I was also interested in how you make those shifts work. Memory is a fracturing of reality, and everyone remembers things differently. I have a visual memory. My memory for names and such is awful.

Jonathan, it was a tremendous pleasure talking to you.

Tosca is at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden 24 May-20 June 2019.

Peter Gynt is at the National Theatre, London 27 June-8 October 2019.