The winter theatrical season in Athens typically comes to an end on the Sunday before Easter – sometimes it may take a little longer but not longer than, say, the end of May. The weather in Athens is very hot during the summer and the formal atmosphere of an indoor theatre is no longer attractive to audiences. There is a plethora of shows, however, that are staged during the summer in open air theatres around the country- including the Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus or the Herodes Atticus Theatre, on the slope of the Acropolis.

As these theatrical productions are meant to go on tour around Greece (sometimes hosted in several dozens of venues), they do not address hard core theatregoers but holidaymakers and locals in the provinces or those few remaining within the city walls, who are after a relaxing night out. To meet the demands of wider, diverse audiences and the high expenses of tours, the directors inevitably have to succumb to market pressures. Playing it safe, they usually choose classic, well-known plays (Greek tragedies consistently being the big hit), popular, well-known protagonists and a conventional staging that avoids surprises, ambiguities and experimentations. Despite the fact that theatrical gems have also been presented over the years during the summer season, the painful truth is that the preference for light, easily digestible shows transforms the performers into commodities and the spectators into consumers.

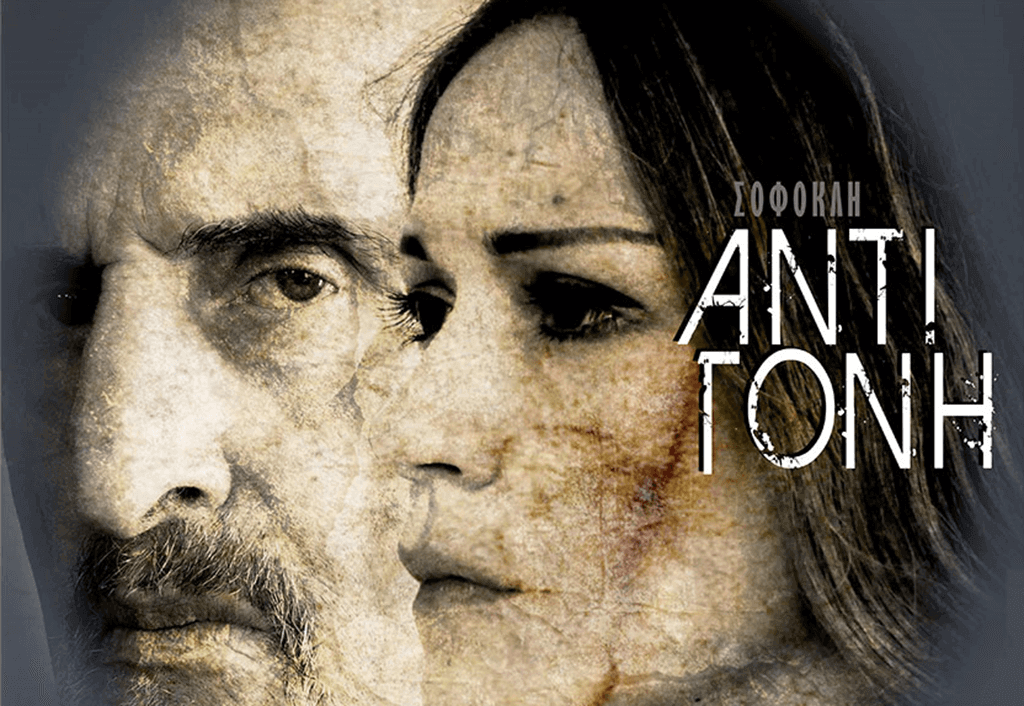

Moumoulides employs this well tried recipe in his Antigone, his staging being a benign, easy rendering of the Sophoclean tragedy. It boasts, though, a couple of memorable performances, Nikitas Tsakiroglou’s being one of them.

Tsakiroglou, an experienced actor with sure command of his expressive means, is perfectly fit for the role of Creon. A careful reader of Sophocles, Tsakiroglou avoids the exaggerations that often reduce the Theban King into a caricature; his Creon is not an arrogant, cruel, or indifferent leader, but a sympathetic King whose good intentions cannot save him from the disaster. Stavros Zalmas in the roles of the Guard and the Messenger was also magnificent; as a Guard, in particular, with his subtlety of acting Zalmas gave value and weight to an often overlooked minor role (usually offered to younger and less experienced actors) that often verges on the ridicilous. Ioanna Pappa, one of the very talented actresses of her generation, on the other hand, did not seem to be up to the standards of the leading role. Her delivery was rather flat and her acting style outdated and, at times, exaggerated. Despite her emotionality since the very beginning of the play, she failed to carry the audience along with her and make them share her pain and distress.

The minimal set (abstract in terms of time and place) is visually interesting but meaningless in the context of the performance, as the director failed to create any significant semiotic associations. The music was, again, interesting; still, I would argue that employing music to create a certain atmosphere would be suitable for drama, not for Greek tragedy.

Overall, this was a production that worked; neither a must-see show, nor a sloppy rendering. It would be a blessing, however, if talented directors like Themis Moumoulides opted to create shows that offer their audiences more than untroubled enjoyment.