Mandisi Dyantyis, the Musical Director of Isango Ensemble and one of its founders and Ayanda Tikolo, a cast member, met with Rivka Jacobson at the Young Vic, where A Man of Good Hope, a new stage adaptation of Jonny Steinberg’s book, is currently performed.

A Man of Good Hope is directed by Isango’s Artistic Director Mark Dornford-May and performed mainly through music. Rivka Jacobson is grateful to Mandisi and Tikko for comments and explanations, which assist with better understanding of the haunting marimbas and the vocal music sang by the 24-strong ensemble, made up of both classically trained and untrained singers from the townships surrounding Cape Town.

Rivka Jacobson: What inspired the music you wrote for this play?

Mandisi Dyantyis: The story is the inspiration for the music. The story moves from Ethiopia, Somalia, which is northern Africa, down to South Africa. And in the process, a lot of countries are visited or at least passed through, so that also dictates the music. It is influenced by the cultures of those countries, but it’s all original music. We have a few traditional songs and a few – what we would call, struggle songs, you know, songs that were sung in the days when people protested, we’ve got those, because when he gets to South Africa there is a lot of protesting. But it’s all original music, it infuses a lot of styles: you get your jazz, blues, you get classical style music, you get gospel, you get everything in it, I guess maybe because the company can do it!

RJ: The main character, Asad, is from Somalia – How much of the local or indigenous music was in your mind when you composed it?

MD: I didn’t want to write music, which was specifically of that place; I wanted to write it as though someone from another country or someone from another place was hearing the music of that place. So therefore you don’t accurately get the music because you’re not of that country, but there’s a sense and there’s a certain sound that you get when you hear it. So when Asad moves from one country to another country he’s met with these sounds, which he doesn’t understand for what they are, the nuances, to say, “This is exactly how it should sound” – but he gets them and they grab him. And therefore in the piece you can see it and know exactly where you are, but a person from that country will tell you that it’s not specific – but it gets the spirit of that country.

If, for instance, I went to China and listened to music from China I would hum something that I perceived to be that, but it probably wouldn’t be exactly Chinese, you know. But what I’m humming and what I get is an essence of what the music is. It’s what I absorbed from that. And so that’s what we’ve tried to do. And of course when we get to South Africa we wanted to be specific, because he spends a lot of time in South Africa, a lot of the story and the major decisions about his life in that period happen in South Africa, and so we needed to differentiate because in South Africa he doesn’t move from country to country, he moves from place to place, from town to town, so you need more specification to know that ‘I’m in a rural area’ or, ‘I’m in a city’. So those divisions become more as you get into South Africa.

RJ: So when you get to South Africa, people from South Africa would know exactly which sounds relate to individual parts of the country?

MD: Definitely. Definitely. There is a sense that – because rural sound is not like the city sound, you know, so we tried to do that. But also there’s an underlying melody, you know, fragments that are always there in our music, because we carry stories within the singing. It needs to resonate and the audience needs to hear what is being said, and so everything that we do is guided by strong melodies, and then everything else we arrange underneath those melodies, to try to elicit a feeling or at least an emotion with that… we speak eleven languages in South Africa, and if you want to think about that there’s thirty subcultures and subcultures and subcultures which function in that country! So therefore, the different styles of music you get are abundant, and if you’re clever enough you can use all of those.

RJ: From what I understand, the actual company is made up of people from Cape Town townships.

MD: I mean, we’re based in Cape Town, the company is based in Cape Town, but you have a lot of people who are coming from outside Cape Town. And because we explore these things, you know, we can experiment with music from anywhere in the country, even in Africa, because music is connected somehow.

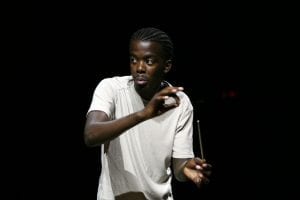

Ayanda Tikolo: I was going to say that, even me, I’m not from Cape Town, I came to Cape Town to study at the university. [Originally from the eastern side of South Africa.] I’m a Xhosa, and he’s a Xhosa, but you’ll find out that our cultures are kind of different. Maybe I’m a Bhaca in the Xhosa side, he’s a Hlubi, but we’re both Xhosa. And his Xhosa is kind of different from mine; his side of Xhosa’s traditional songs are different from mine. So then, in our company we came from different places in South Africa, maybe, then we went to Cape Town maybe to find a better life, and we found this company, and then it was like, a joint venture of people. And that’s why it’s so easy for our music director to explore different sounds of music, because I have my kind of knowledge of my culture’s style of music, and he has his own, and another person has his own too.

MD: Every movement, every uprising – in America it was the Civil Rights Movement, you know? They had songs that spoke about – they had songs of that era, you know. And so in South Africa – because it’s changed – The landscape of fighting for people’s rights and all those things have changed, it’s changing all the time. But it’s all about the message of those songs; they carry a certain rhythm, which is forceful.

RJ: You wrote the music; how did the lyrics come about?

MD: First of all the lyrics come from the book. That’s the first thing, so we adapted the book. David Lang  worked on the script together with the company, and because it’s a – we work differently than other companies, I don’t come with a full score of music the first day of rehearsal, and the script is not finished when we start the first day. It’s all workshops and ideas being thrown around.

worked on the script together with the company, and because it’s a – we work differently than other companies, I don’t come with a full score of music the first day of rehearsal, and the script is not finished when we start the first day. It’s all workshops and ideas being thrown around.

We start with a blank space, you know, because we know the talents in the room, we know what is possible. So we don’t come there with the script, like, “Here is your script, read your part” – especially with music, you know, we have to see how it evolves. Because I might think someone is going to sing that song but no, another person is going to sing that song. So that song will change, because it’s going to be sung by someone else who can’t do that. It’s things like that. We think this section won’t have music but then we realise this section should have music, so then music has to be written quickly, you know, it all changes.

RJ: Let’s talk about the operatic element. There is a soprano, tenor and baritone. Did you write the operatic parts in order to please a Western audience?

MD: First of all, a lot of our guys are classically trained, maybe ninety percent of our guys are trained and they sing in choirs. So there’s a big choral culture, and it’s a natural thing to gravitate towards that. And if you know our pieces in the past, we’ve done La Bohème, we’ve done Magic Flute, and we’ve done Carmen. So we’ve done that, it’s a skill at our disposal. We write them because we can write them. We write them to try and break the idea that ‘this is Western music’ or whatever, this or that. Because at the end of the day, as a company, we have a company sound. So if you’re listening from outside you might hear certain different elements that you can take away, but it was our intention to say that Africans can do this, Africans can sing this; they can do other things.

We need to break that stereotype that says that only people like this can do this. So therefore you have a person in a tracksuit and a Rasta t-shirt singing a tenor part, and you go, ‘That’s not done, I haven’t seen that before.’ Because we can do it! That’s one thing. But it also plays a crucial part in telling the story, because when you hear that voice, suddenly, the soprano voice coming out of nowhere in the end of the piece for instance, and it tells you a story that, ‘I was here and I was moved there, and my child was there,’ and you listen to it because it’s used as an effect, rather than as an aria. People come to me and say, ‘ooh, that was a very good aria that you wrote,’ and I think, ‘I wasn’t writing an aria, I was just trying to tell the story and convey this emotion in a different style.’ You know, he comes there and he pushes a lot of narrative with these songs; he says things which would not necessarily be received better by the audience if he was speaking them, and he’s got a beautiful baritone voice. So you write things like that because you want to push the story forward. But you must also listen to what’s happening underneath: he’s being accompanied by marimbas, but he’s singing something which would be themed as recitative in a classical piece. So we flip it, because we can do it.

RJ: The instruments you used in the performance – Why did you select those instruments in particular, and how you used them?

MD: We use instruments called marimbas. In the Western classical style, they are known probably as xylophones. They are different in every part of Africa – in Zimbabwe they are called balafons, in Mozambique they are called something else. And ours in South Africa are built in a place called Grahamstown, they are made of wood. They are very simple instruments, made of wood and they have a sound box at the bottom. But they are instruments, you know? It’s funny that the West has always treated African instruments as something else, because a trumpet is a trumpet, you know. The trumpet was played in exactly the same way in the eighteenth or twentieth century as it is now today. And that hasn’t changed.

And we never comment on the fact that we are doing that. So these instruments, we treat them like that, we give them the same importance: that they are instruments and they can do so much. They can play soul music; they can play vibe-y, rhythmic music; they can play disjointed music; they can play what you call sustained music – because we allow them to do that. And a lot of people have been surprised, even South African people or marimba players who play these instruments – because we have treated them as instruments that you would find in an orchestra, and we practice them, and we want to be as technical as possible in playing them. They do all of that, so therefore they will be accompanying him in an aria, and then accompanying someone else in their twelve bar blues, and then accompanying someone else in their death scene, and someone else in a pop song – because they can do that. They’re not restricted by anything, it’s just in the mind of the player and the mind of the person writing the music, in saying: ‘This is an instrument that can do that.’ In the way that the trumpet can play classical music; can play jazz music.